Marilyn Monroe Productions, Inc.

1955

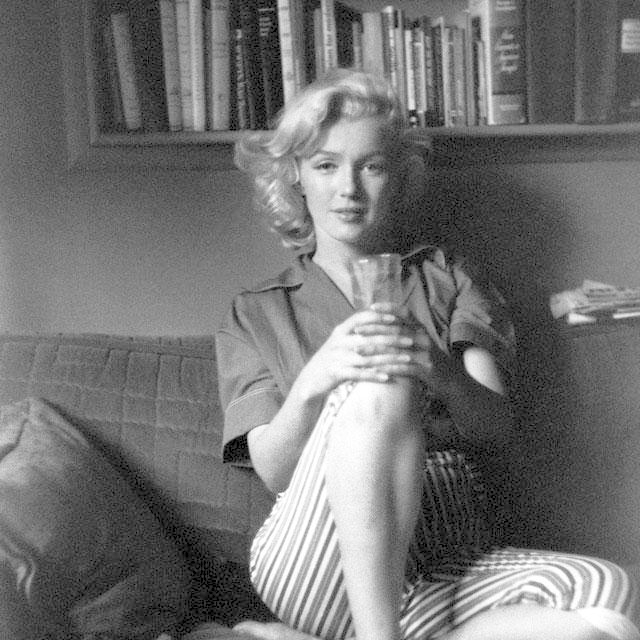

Following Mary Picford’s Example

January of 1955 delivered Marilyn to the home of Frank Delaney, Milton Greene’s attorney, where she broke her silence and announced to a room jammed with reporters the formation of her own production company. While Marilyn would be the corporation’s president. Milton Greene would be its vice-president. We will go into all fields of entertainment, she said, but I am tired of the same old sex roles. I want to do better things. People have scope, you know (Spoto 303). When she was asked about her status with Fox, Frank Delaney interrupted and answered that Marilyn Monroe was no longer obligated to Fox because they were in breach of contract. A few cheered Marilyn’s announcement; but a few jeered it, mocked the dumb blonde for even trying such a dangerous and complex business adventure. Fox reacted with panic.

But Marilyn was in a wonderful mood. Not only was full control of her career within her grasp, in the Spring she had reunited with Arthur Miller through some new friends, poet Norman Rosten and his wife, Hedda. Norman was a classmate of Arthur’s at the University of Michigan. For a while she maintained a relationship with both the playwright and the retired baseball player. The former she planned to marry. The latter she had just divorced. The retired baseball player, however, would never be completely gone from Marilyn’s life.

On April the 8th, Edward R. Murrow interviewed Marilyn, along with Milton and Amy Greene, on his live television program, Person to Person. Was that Marilyn Monroe? The unadorned woman who answered Ed’s questions flashed her usual engaging, million watt smile, but something was different: she appeared almost diffident, ill at ease, absent was the confident swagger of the Blonde Bombshell and the world’s biggest movie star. When asked to explain why she founded her own production company, Marilyn hesitated briefly, then replied: Primarily to contribute, to help making good pictures. It’s not that I object to doing musicals and comedies―in fact, I rather enjoy them―but I’d like to do dramatic parts, too (Spoto 321). She seemed unsure. Despite her shaky performance before the television camera, her future appeared to be full of promise and her journey to becoming a serious, respected actress appeared to be accurately charted.

Marilyn began to frequent The Actor’s Studio, leading to a close friendship and serious study with Lee Strasberg, America’s Konstantin Stanislavski and considered by many to be a genius. He encouraged actors to invoke their memories of pleasure and pain, their memories of the past to create realistic characters and realistic performances. He recommended psychotherapy for his students. Marilyn was willing to do whatever she needed to do to become a better actress. She was ready to cast-off the dumb blonde persona, find the real person behind that cloak and create a new, an improved Marilyn Monroe. Perhaps dredging up memories of past fears, misery, loneliness, suffering and pain was not, in Marilyn’s case, at all therapeutic. Even so, she began counseling sessions with Dr. Margaret Hohenberg, a psychiatrist who was also treating Milton Greene. Marilyn would not correct this odd, triangular relationship for two years. Right at that moment, she needed to make a more pressing correction; she only needed to complete one piece of business before the new person, the new respected actress could be realized―the completion of, and hopefully, her final dumb blonde role.

Earlier in January, Marilyn had flown to Hollywood and appeared at Fox studios so Billy Wilder could recreate the subway grate scene on the back lot. The footage shot in Manhattan could not be used due to crowd noise. After submitting once again to multiple takes, filming for The Seven Year Itch ended. All that remained was the movie’s big opening night.

On her 29th birthday, Marilyn transformed herself into the glamorous Movie Star once again and attended the movie’s World Premiere in Manhattan on the 1st of June in 1955, escorted by her now ex-husband, Joe DiMaggio. In a theater filled with fans and many of Hollywood’s royalty, Marilyn was her usual dazzling self, cavorted playfully on the CinemaScope screen as TheGirl, Richard Sherman’s unnamed upstairs neighbor. As the buxom but sweet and naive toothpaste model who incites Richard’s overly active imagination, Marilyn delivered a remarkable performance, beautifully natural and funny. As the premiere came to an end, those in the theater stood and applauded. The success and popularity of the movie delivered her into a singular pantheon of fame, occupied by only her. The unwanted waif who had lived a nomadic childhood was now the biggest, most powerful movie star on Planet Earth, a global personality, a singular symbol of glamour, feminine beauty, playful, innocent sexuality, every heterosexual man’s ideal and fantasy.

Charles Feldman, who produced The Seven Year Itch, received word from reliable sources that Marilyn might not return to Hollywood. She was just that dissatisfied with her shabby treatment, her insufferable type-casting and disregard for her opinions and goals. Charles’ sources told him that Marilyn was happy with her new life in Manhattan and her New York friends, many of them the intelligentsia of the art world and the world of theater, including Carl Sandburg, Truman Capote, Norman Rosten, Tennessee Williams and of course, Arthur Miller. She believed they accepted her; she felt like she finally belonged. Hoping to convince her that she could still obtain what she wanted in Hollywood, Charles threw a party in Marilyn’s honor.

Again, Hollywood royalty attended: Darryl Zanuck, Warner and Goldwyn, Gary Cooper, Claudette Colbert and Loretta Young, Clifton Webb, Humphrey Bogart and her director, Billy Wilder. But the one man paying homage to her that evening who excited her the most was Clark Gable, Norma Jeane’s imaginary father. During a dance with her idol that evening, she told Clark how much she admired him; and he told her that she had the magic, that he wanted to make a picture with her. It was settled, then, that night: she and Clark Gable would eventually make a picture together for her production company. She was congratulated and complimented by all in attendance. Even Darryl Zanuck remarked that her performance as TheGirl was more than special. She must have felt vindicated. Always the gorgeous diplomat and ever the cajoler, she gave all the credit to her director, Billy Wilder: It’s because of Billy. He’s a wonderful director. I want him to direct me again but he’s doing the story of Charles Lindbergh next, and he won’t let me play Lindbergh (Spoto 297).

In spite of Marilyn’s remarkable performance as TheGirl and the huge success of The Seven Year Itch, the rancor of legal conferences between Fox’s lawyers and Milton’s lawyers had consumed most of 1955, particularly its closing months. What a waste of time, it seems: Fox had a contract ready for Marilyn to sign before the end of the year, an agreement that acceded to all of her demands.

Fox finally agreed to pay the $100K bonus promised to Marilyn for appearing in There’s No Business Like Show Business. She agreed to make four movies for Fox over the next seven years. For each movie, she would receive a fee of $100K plus an additional $500 per week for expenses. These amounts would be paid by Fox directly to her production company, thus creating a tax shelter.

Assignments of which she did not approve, she could refuse without repercussions. Subject matter, script, cinematographer, and the all important director, were subject to her approval. For each movie she made for Fox, she could make another for any studio of her choice and she could also make studio audio recordings, appear on the radio and television.

One casualty of Marilyn’s new life, her production company and her relationship with the Greenes and the Strasbergs, was Natasha Lytess. Some say the Greenes, while some say the Strasbergs, and others say Arthur Miller convinced Marilyn to end her relationship with Natasha. The drama coach who had been with Marilyn for eight years and twenty-two movies, found herself dropped. Since Paula Strasberg had become a part of Marilyn’s life, she no longer needed Natasha; and excising her former coach simply proved, some contend, what a selfish and heartless woman Marilyn actually was. Not often mentioned, however, for many of her years with Marilyn, Natasha often earned more money than the movie star: the studios paid Natasha a salary while Marilyn paid her an additional fee for her private lessons and her exclusive assistance; and Marilyn stood by Natasha when many wanted her fired. Marilyn commented on more than one occasion that Natasha was often critical and demeaning. Some contend that Natasha was in love with Marilyn and her desire to be more than just Marilyn’s drama coach remained unrequited, causing the older woman to become bitter and critical. Perhaps Marilyn was tired of Natasha’s criticism and the sexual expectations; perhaps Marilyn was just moving on: there simply could not be two drama coaches in her life. We will never know why Marilyn ended her relationship with Natasha suddenly and completely. The student never again spoke to or about her former housemate and teacher.

A hectic and tumultuous year, 1955 ended with a sedate champagne party in the Greene’s Connecticut home. They, along with Marilyn and Arthur Miller, celebrated an incredible and hard won victory over the mighty Darryl F. Zanuck and Hollywood’s studio system. Arguably, the formation of Marilyn Monroe Productions all but ensured the ultimate collapse of that chauvinistic, oppressive but extremely successful system, and announced the arrival of a shrewd businesswoman.