Iván Haidabura

1949

The Powerful Starmaker

Depending on which account you choose to believe, Marilyn either met Iván Haidabura, otherwise known as Johnny Hyde, at a 1948 New Years Eve party or during a photo shoot at the Palm Spring’s Racquet Club in January of 1949. The party, thrown by Spiegel Productions, led to an immediate trip to Palm Springs, some contend, and a new romance. Another version claims an advance screening of Love Happy piqued Johnny’s interest in Marilyn. In My Story, Marilyn claims she learned about the part at Schwab’s Pharmacy and went to the set in search of the movie’s producer, Lester Cowan, who took her to Groucho and Harpo for an audition. Yet another version claims that Johnny convinced Lester Cowan to cast her in the movie; and then Cowan devised the cameo, walk-on part just for Marilyn. Both Marilyn and Groucho contradicted the latter version since both eventually recounted her memorable audition. What we know for sure is this: at some point, and prior to her role in The Asphalt Jungle, Johnny became one of the most vital persons in Marilyn’s life, both personally and professionally.

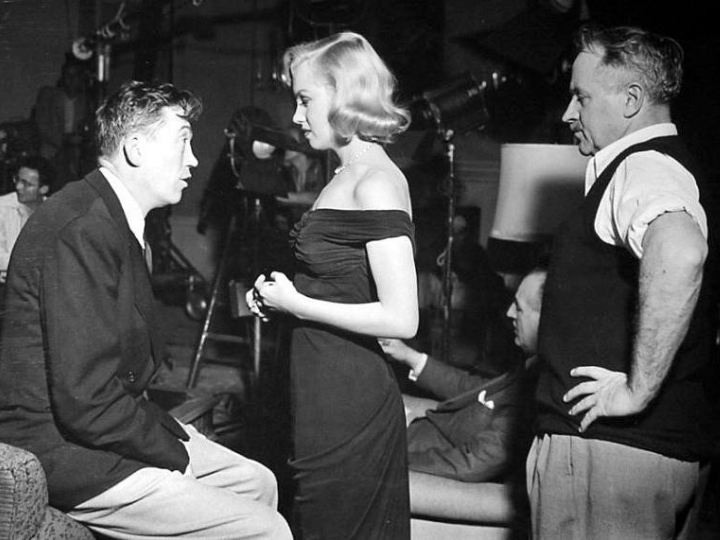

In My Story, Marilyn wrote: Johnny Hyde gave me more than kindness and love. He was the first man I had ever known who understood me (Monroe 133). One of the most powerful agents working in the City of Angels, he represented several of the angels who resided there, including Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner. VP of the prestigious William Morris Agency, Johnny purchased Marilyn’s contract from Harry Lipton, the agent representing her at the time, and committed himself to making her into the movie star she wanted to become. He is credited with securing her the part of Angela Phinlay in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle; however, as is often the case with Marilyn’s personal life and career, others involved recounted different events surrounding her casting. According to the movie’s producer, Arthur Hornblow, Marilyn was not impressive in her initial audition for both him and Huston. In fact, despite Johnny’s entreaty, John Huston was not going to cast Marilyn as Angela until Lucile Ryman interceded and forced the director to reconsider his decision. Huston boarded his Irish stallions at the Carrol’s ranch and for that service, he owed $18K. Lucille and John threatened to sell Houston’s stallions to pay his debt unless he agreed to give Marilyn another chance along with a screen test. Huston agreed. Lucille notified Louis Mayer, who attended the screen test. Impressed with Marilyn, according to Lucille, Louis Mayer decided to cast Marilyn as Angela Phinlay, not John Huston (Spoto 161). On more than one occasion, the director confessed that Marilyn impressed him more off-screen than she did on-screen; but always willing to accept credit for something in which he had little or no part, he also said that Marilyn was nearing oblivion before he cast her as Angela, suggesting that he both, and at the same time, started and saved her career.

Natasha continued to stress good posture and diction during Marilyn’s lessons; and then in February, Marilyn received $500 for an afternoon of filming on Love Happy and an additional $300 to pose for publicity stills afterwards. In March, with Johnny Hyde now involved in Marilyn’s life, the Carrols ended her $100 stipend and she moved into a one room apartment at the Beverly Carlton Hotel. Johnny had fallen deeply in love with his young mistress and was determined to make Marilyn his bride. In late spring, he left his wife and family, even though Marilyn asked him not to, and rented a house at 718 North Palm Drive in Beverly Hills. In spite of Johnny’s constant proposals, Marilyn steadfastly refused to marry him. She loved him, she confessed, but not in the way that would allow her to marry him. Already suffering from serious heart disease, he knew he was not going to live much longer. He openly suggested to Marilyn, if she married him, since he was a wealthy man, his death would provide her with financial security, a large inheritance. Even Joe Schneck tried to convince Marilyn to marry Johnny, as did many of Johnny’s friends; but she continued to refuse. Although she maintained her one room hotel apartment, she spent most of her time on North Palm Drive with Johnny and Natasha.

In early May, she arranged some of her old photographs into a portfolio, found Tom Kelley’s business card and approached him about some modeling work. He placed her on a beer poster, one that caught the attention of Baumgarth Calendar Company. The owner wanted Marilyn to appear on his next calendar. Would she pose completely nude? Tom asked. Having already posed topless for painter Earl Moran, she agreed, provided Tom’s wife, Natalie, was present during the session and the photographs were not vulgar. So on May the 25th, she arrived at 76 N. Seward in North Hollywood and on a pallet of crumpled velvet, posed nude. For her poses on that Wednesday evening in May, Mona Monroe, as she signed the photographic release form, received $50. Baumgarth paid Tom Kelley $500 for two photographs of the nude Marilyn Monroe. Those now famous images of her unclothed body, entitled New Wrinkle and Golden Dreams, are neither vulgar nor especially provocative in retrospect; but, at the time, they generated quite a controversy. Despite the shock and the objections of some, the poses positively impacted her movie career. With the approval of others, however, they launched a magazine dynasty.

Lester Cowan prevailed upon Mona Monroe to involve herself, fully clothed, in a publicity and exploitation tour for Love Happy. He offered her $100 per week for the six week tour and a cash advance to buy a new wardrobe. In early June, she embarked upon an all expenses paid tour of Rockford and Chicago, New York City and points in between. For most of June and all of July, she appeared in restaurants enjoying dinner with men she had never before met; she appeared at various functions and events she knew very little about. She was posed and photographed, watched and even ogled, often asked silly questions that she dutifully answered. I spent several days in New York, she wrote in her incomplete autobiography, looking at the walls of my elegant suite and the little figures of people fifteen stories below. All sorts of people came to interview me, not only newspapers and magazine reporters but exhibitors and other exploitation people from United Artists … But I saw nothing and went nowhere (Monroe 106-107).

During her Love Happy Tour, she received her first recognition from the men in the United States military when, in June, a publication for the United States Marine Corps, Leatherneck magazine, featured a full page pin-up and named Marilyn their Pin-Up of the Month. In July, First Marine Division, before they embarked for Korea, crowned her Miss Morale of the Marine Corps. Stars and Stripes named her Miss Cheesecake on more than one occasion and many various marine divisions also named her their Miss Morale. The 31st Polar Bear Regiment awarded her the honor of being the girl we should most like to get a bear hug from. The most prescient honor, however, came from soldiers stationed in the Aleutians who named her the girl most likely to thaw out Alaska. The military branches competed intensely for Marilyn’s attention and her affections. When Marilyn appeared in a photograph with three sailors aboard the USS Manchester, engaged in a bear hug, the Polar Bears expressed dismay, left her title intact but suggested that the Navy should find their own pin-ups.

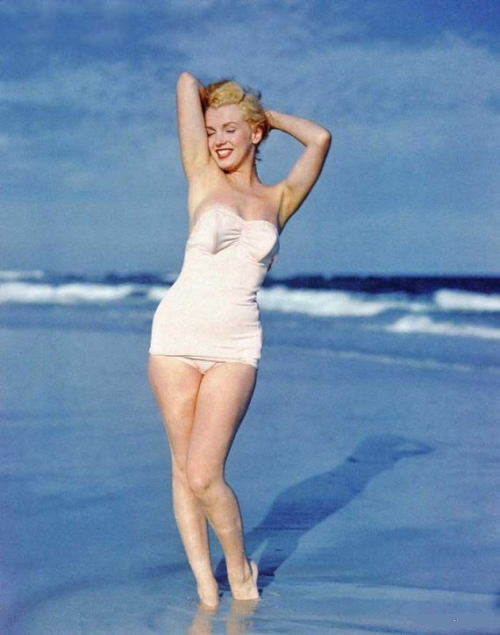

In New York City on an assignment, Andre de Dienes located Marilyn at her hotel and convinced her to pose for him on the beaches of Long Island. Dressed in a one-piece white swimsuit, Marilyn cavorted like a water nymph on the beaches and ran through the ocean’s spray as Andre snapped some of the most endearing photographs ever taken of her. Later, he attempted to reignite the passion he claimed they had shared one night during their trip to Oregon in 1945; but Marilyn rebuffed his advances. A scheduled interview the following day, she told Andre, required that she look her best, at least rested.

Interviewer Earl Wilson wanted to find out what this Mmmm Girl, as Marilyn was being called by the publicists, was all about. So on Sunday, the 24th of July, Earl arrived at the hotel to interview the Mmmm Girl, only to be unimpressed. She was a dull interview, according to Earl, just a woman with a tiny waist, 36 1/2 bra line and long pretty legs, not a woman who could make any sort of claim to acting genius (Spoto 136). That was Marilyn’s initial encounter with an unfavorable article and unflattering press, something with which she would become all too familiar in just a few short years.

On August the 5th, Marilyn found herself in Milwaukee for an August the 6th premiere of Love Happy. By this point in her publicity junket, Marilyn was weary and tired of the road. In My Story, she recounted her decision to leave the publicity tour in Rockford, Illinois: In Rockford I decided that I had seen enough of the world … After sitting in the lobby of a Rockford movie theater, ‘keeping cool’ in a bathing suit and handing out orchids to ‘my favorite male moviegoers’ I told the press agent that I would like to return to Hollywood (Monroe 107). Without notifying Lester Cowan, a decision that caused a serious rift between them, she ended her participation in the publicity tour and returned to Southern California. Back in Hollywood in early August, Johnny helped her land the part of Clara, a burlesque troupe member in Fox’s odd cowboy musical comedy, A Ticket to Tomahawk. No acting required.

September of 1949 was a significant month for Marilyn. While Johnny vacationed, she attended a party at the residence of Rupert Allan and Frank McCarthy. While there she met Milton Greene, a rising star in the world of photography. Enthralled, she spent most of the evening talking with and listening to the young and handsome New Yorker as he spoke about painting with the camera (Spoto 158). When the party ended, she followed him to his bungalow where the conversation and the talk of possible future plans unfolded. Some maintain, a brief, but passionate romance began, one of many liaisons that Marilyn putatively had with photographers, a profession the practitioners of which, some say, she often could not resist. But Milton soon returned to the East Coast. Milton Greene’s wife, Amy, maintains to this day that her husband and Marilyn were never lovers even though they had a unique and close relationship, more than just a normal friendship. According to Amy, Marilyn would never have betrayed her. Also, Marilyn stated that she was faithful to Johnny Hyde during their brief affair, although he was often distrustful; and she could not mitigate his fears that she would turn to other men.

Marilyn had no time to miss Milton Greene, her new friend, soon to be dedicated photographer and business partner. Her audition and screen test for The Asphalt Jungle occurred in late September, and in early October, she signed a contract to portray Angela Phinlay for John Huston. Love Happy premiered in San Francisco in mid-October. Marilyn’s appearance with Groucho Marx boosted to her name recognition. Although Love Happy was actually Marilyn’s fourth movie, she was credited with an introductory announcement as if the slap-stick comedy was her first.

Filming with Huston consumed the end of the year along with posing for an occasional pin-up. Marilyn still believed that Grace’s prognostication for her was correct: stardom still awaited. So as the old year came to an end, she continued her acting lessons with Natasha Lytess and her relationship with Johnny Hyde. With anticipation, proud of her performance as Angela Phinlay, she prepared for the mid-century year of 1950 to arrive. With the new year came her unexpected return to 20th Century-Fox.