Mr. Giuseppe Paolo DiMaggio

1952

The Yankee Clipper

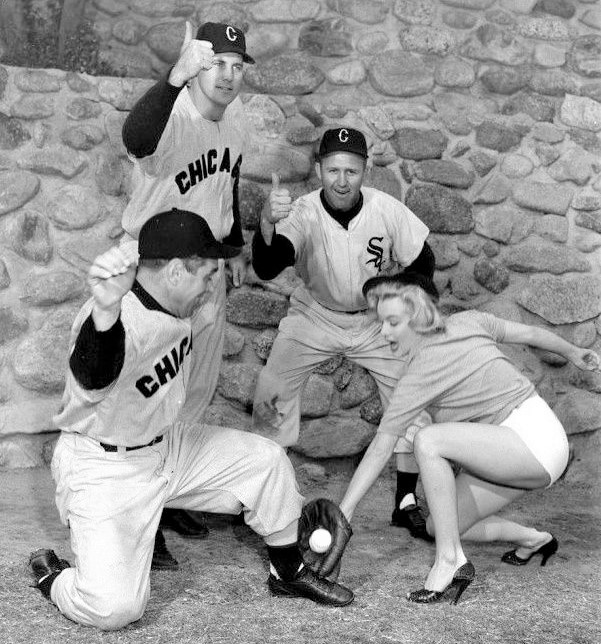

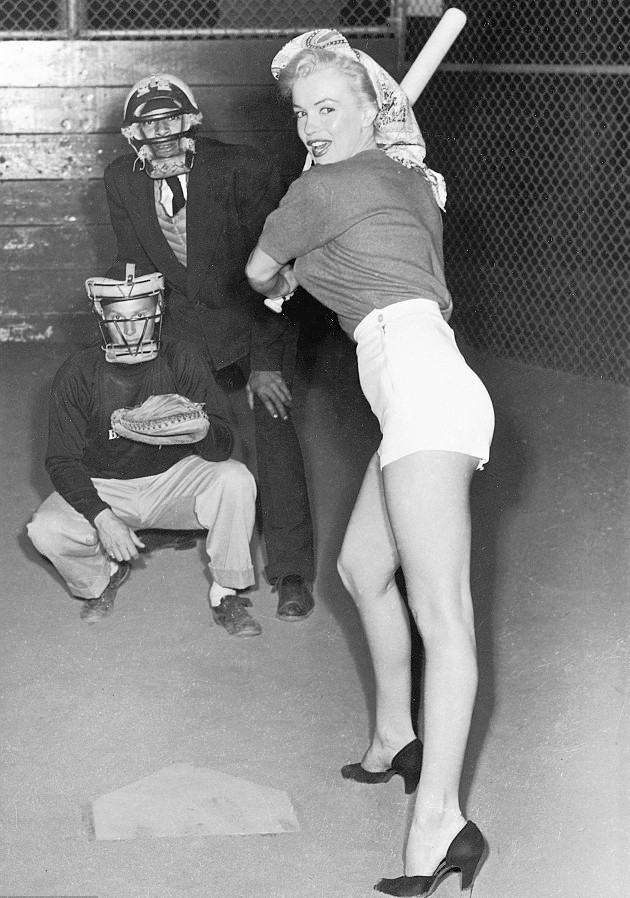

Joe DiMaggio was still America’s reigning baseball hero in 1952 despite his retirement a year earlier. An icon himself, he was known coast to coast and around the world as either the Yankee Clipper or Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio. A cute publicity photo of Marilyn dressed in revealing white shorts, holding a bat over her head while standing at home plate, preparing to smack a baseball, caught Joe’s attention. He misinterpreted the photograph as an expression of Marilyn’s interest in baseball; so Joe asked a mutual friend to arrange an introduction. In spite of her misgivings, Marilyn agreed to have dinner with the world famous athlete; but she found, after arriving two hours late, that she was unexpectedly attracted to her laconic dinner date, a reserved gentleman in a gray suit. After he said I’m glad to meet you, Marilyn’s dinner date fell silent for the whole rest of the evening (Monroe 161). Marilyn was confused, and also bemused, by Joe’s quiet demeanor. She concluded that Joe DiMaggio was not prodigal with words; and as other men in the restaurant began to notice him, they began to gather. Marilyn noticed something different and unique about the baseball legend.

The men at the table weren’t showing off for me or telling their stories for my attention. It was Mr. DiMaggio they were wooing. This was a novelty. No woman had ever put me so much in the shade before. Sitting next to Mr. DiMaggio was like sitting next to a peacock with its tail spread—that’s how noticeable you were (Monroe 162-163).

Randy Taraborrelli and Stacy Eubank report that Marilyn actually met Joe earlier than 1952. According to Taraborrelli, they met in Hollywood in 1950. According to Stacy, Marilyn initially met Joe in August of 1951 when she traveled to New York City to observe Carol Channing in the Broadway stage production of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Marilyn was betting on being cast as Lorelei Lee even though Betty Grable was scheduled to receive the part. Stacy acknowledged Taraborrelli’s account of a Brown Derby Restaurant meeting in 1950, only to dismiss it as occurring too early in Marilyn’s life to be more than just an incidental and casual meeting: Marilyn was still involved with Johnny Hyde. Also during this August trip in 1951, according to Stacy, Marilyn initially met not only Mr. 56 but also the renown acting instructor, Lee Strasberg.

After they began to date publicly, Joe and Marilyn became America’s most famous couple; but much to the chagrin of the conservative Italian, his girlfriend was recognized as the nude model appearing on a calendar hanging in bars, barber and automotive repair shops across the US. The story that Marilyn had posed for the scandalous nude photographs in 1949 broke to the public in March.

Fox ordered her to deny that the sexy blonde was even her, but Marilyn refused to lie. She was not ashamed, so she admitted that she had posed nude: she was all but destitute and needed money. The public understood, accepted her explanation, admired her honesty and she attained an odd celebrity for the fifties. A few condemned her for what they called her immorality. Some even called her a whore. But the majority in America, men and women, tired of the puritanical mores forced upon them by powerful religious groups and even the government at every level, embraced Marilyn’s unabashed celebration of her body and her sexuality. To them, her refusal to lie or apologize was refreshingly powerful and ignited what would later be christened The Sexual Revolution.

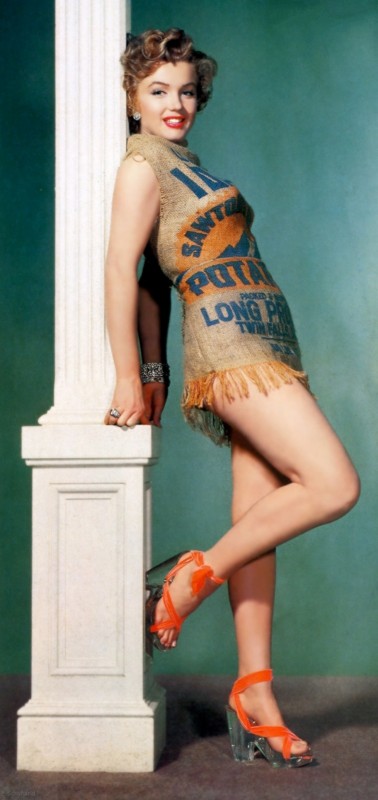

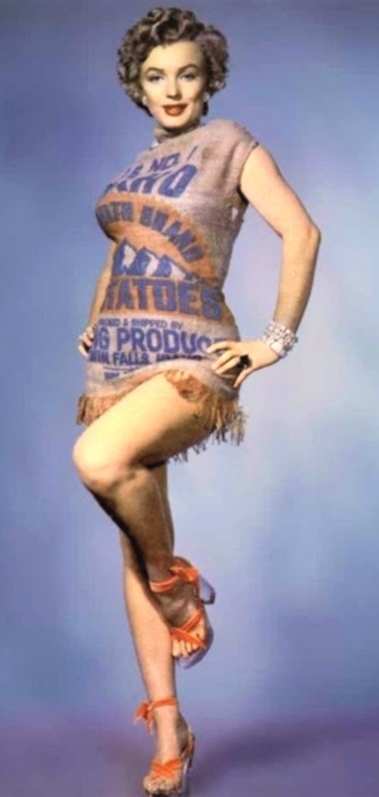

In January of 1952, the Foreign Press Association of Hollywood nominated Marilyn to receive their first Henrietta award as the Best Young Box Office Personality. She attended the awards ceremony, held at the Club Del Mar in Santa Monica, wearing a provocative and alluring red velvet gown once worn by Gene Tierney. Gene did not cause the same brouhaha as Marilyn. Even though she won the gargantuan statue, some in the press, and some in attendance, considered Marilyn’s attire to be unnecessarily vulgar. This would not be the last time she found herself as the subject of criticism, even ridicule, for her wardrobe selections. This particular incident led to the photographs of Marilyn wearing a potato sack just to prove that she was sexy regardless of what she wore. Fox’s publicity manager, Harry Brand, arranged for Earl Theisen to take the now famous stills; but the potato sack worm by Marilyn was actually a custom-made, burlap dress designed by Fox’s famous costume designer, William Travilla.

Of the five movies in which Marilyn appeared in 1952, two offered little, if any, impetus for her career: We’re Not Married and O’Henry’s Full House, each of which featured ensemble casts appearing in short vignettes. Her role as Annabelle Jones Norris in We’re Not Married was devised just to display Marilyn in a swimsuit. But as Peggy, the rough and tumble cannery worker in Fritz Lang’s Clash By Night, the final film in her Impression Trilogy, Marilyn starred alongside Barbara Stanwyk and Robert Ryan and delivered a compelling performance. Many of the Americans who went to the theaters on June the 14th probably went because of the nude calendar controversy; but Marilyn proved once and for all that she could deftly handle a dramatic role. The word sent to Hollywood from New York City and Fox’s corporate offices was this: do not discount Miss Monroe and find parts for her. Zanuck tested her for the odd psychological drama, Don’t Bother to Knock, and awarded her the complex part of Nell Forbes, a troubled babysitter hired by a New York hotel. Marilyn’s subdued and nuanced performance was not well received by the critics but certainly dispelled any concerns that she was only a pretty face and a beautiful body.

As America’s fastest rising movie star, Marilyn appeared in a farce involving chimpanzees, everlasting youth and Cary Grant. In Howard Hawks’ Monkey Business, the final film in her silly secretary trilogy, Marilyn portrayed Lois Laurel, a dim-witted but sexy secretary whose employment is primarily a recognition of her physical assets. Lois represented Marilyn’s first fully realized incidence of her sweet, dumb blonde persona. She also displayed impeccable comic timing and thereby established herself as a preeminent comedienne, a talent that Howard Hawks would soon exploit.

Marilyn traveled to the East Coast in September for the world premiere of Monkey Business. Atlantic City featured her in a parade, and she received a Key to the City from its mayor. He received a big thank-you-kiss from the twenty-six-year-old beauty. Later that evening, on the Boardwalk, thousands of fans welcomed Marilyn as she entered the Stanley Theater. While her glamour mesmerized New Jersey, she also visited hospitals and orphanages. As usual, she made her handlers wait as she visited with each and every child, each and every person. On October the 14th, Bernard Selber crowned Marilyn Miss Medical Center Aides of 1951 and on the 4th of November, she attended their annual dinner at the Ambassador Hotel. Newspapers across the country displayed a photograph of the City of Hope’s president placing a crown on Marilyn’s head: she had become the starlet that every person in America was beginning to notice. As 1952 headed toward New Year’s Eve, Marilyn occupied herself on the sets of pictures that would not only make her a star but the biggest star in Hollywood’s galaxy. But first, the holidays awaited.

Upon arriving at her apartment on Christmas Eve, after attending a studio party, she was greeted by a roaring fire, a beautifully decorated tree, lots and lots of flowers and Santa Claus in the form of a tall, former baseball player bearing many gifts, one of which was a full length mink coat. Marilyn later remarked that the Christmas of 1952 with Joe was the happiest Christmas of her life. A sparkling fireworks display on New Year’s Eve, was harbinger of the explosion to come; and soon, a crown of another type, one that signified her rise to stardom, would be placed on Marilyn’s head.