Clash By Night

16 June 1952

Marilyn’s Impression Trilogy, Movie No. 3

After an absence of ten years, Mae Doyle returns to her hometown where her younger brother, Joe, still lives in the family house. In spite of the apparent friction between them, Joe agrees to let Mae move into their deceased Mother’s bedroom. At the suggestion of Joe, and with his help, the shy fisherman, Jerry D’Amato, who is also Joe’s boss, arranges a date with Mae. Date night takes the couple to the local movie screen where Jerry introduces Mae to his best friend, projectionist, Earl Pfeiffer. After Earl finishes his shift, the trio embarks for the Pavilion and a drink.

Earl is deeply cynical and admits that he doesn’t like women, particularly his expensive, money-eating wife, an untrustworthy burlesque performer who is on the road constantly, doing God knows what. After Earl leaves the bar, Mae tells Jerry that she does not like his arrogant friend; but when Jerry leaves the table to get Mae a fresh beer, her facial expression implies that she is thinking about the projectionist.

In spite of Mae’s interest in Earl, she and Jerry continue to date exclusively and spend a considerable amount of time together. For Jerry, the friendship develops into a one-hearted romance. One night, while they are on his fishing boat, Jerry tells Mae he’s happy she came home. Why? she asks. He answers: You know I’ve always liked you, Mae. Mae asks the fisherman if he has fallen in love with her. He admits that he has; and even though he never actually proposes to Mae, she assumes that Jerry wants to marry her. She flatly dismisses his unspoken proposal because It’s silly for me to even consider such a thing. It’s wrong; but after an unpleasant encounter with Earl during a group get-together that includes her brother, Joe, and his girlfriend, Peggy, along with Jerry, Mae changes her mind and agrees to marry the fisherman.

The wedding and the celebration afterwards are joyous and merry, suggesting a bright future for the D’Amato family. During the joyous event, Mae avoids Earl’s attempt to kiss her. Angered by Mae’s overt rejection, Earl leaves the festivities.

Time passes inexorably. During the ensuing year, Mae becomes pregnant and gives birth to a daughter, Gloria. Family life agrees with Jerry. He is happy and content. He has found his personal paradise.

It is a hot and sweaty summer night when Earl, invited by Jerry because he feels sorry for his now divorced friend, arrives at the D’Amato home for a visit. Earl is extremely drunk. He humorously presents Mae with a bottle of vitamins as a gift and then passes out in the back porch rocking chair. Like the good friend that he is, Jerry carries Earl into an empty bedroom and puts him to bed. While Jerry and Earl sleep, Mae stands at the bedroom window, smoking a cigarette. She appears dissatisfied and restless. Is she thinking about the exciting, beguiling world outside? Is she thinking about Honolulu, which she had mentioned earlier; or is she thinking about the projectionist in a nearby bedroom? Both perhaps? After Jerry leaves the following morning, and in spite of some cruel, harsh words that pass between Earl and Mae while they are alone in the D’Amato’s kitchen, Earl grabs Mae and declares his love. Help me, Mae, he begs; can’t you see I’m dying of loneliness. Earl attempts to kiss her by force; she resists, momentarily, and then succumbs, first to a passionate kiss and then a passionate affair.

Fundamentally, Clash By Night is a common and simple tale about marital trust and betrayal in the form of adultery, that rather hackneyed and oft repeated tale about the wrong choices made by two disenchanted persons who become involved in an extramarital affair which nearly leads to murder.

Based on a stage play written by Clifford Odets, who believed that the natural world represented order and purity while the man-made world represented chaos and corruption, Clash By Night offers its audience plenty of bluster, surface gloss and shine along with darkness, symbols and metaphors, common for director Fritz Lang. The British Film Institute anointed Fritz the Master of Darkness. He was inclined to see both the natural and the man-made worlds as chaotic and corrupt and both equally as violent. Lang satisfies his proclivities, and those of the playwright by providing Clash By Night with an ample amount of chaos and corruption, violence and visual poetry. Clifford and Alfred Hayes provided all the purple dialogue, which erupts here and there, common for a blustery stage play but uncommon for a movie that strives for naturalism.

Despite its hackneyed plot, Clash by Night is an interesting movie, due to the generally fine acting and Fritz Lang’s visual style, a style he developed during his early career during the silent movie era. Then movie makers could not rely on the spoken word to deliver meaning and context. Thus, Lang learned to use visual imagery to foreshadow action yet to occur and to comment on action already passed; and he effectively employs the technique in Clash By Night, a technique that enhances an otherwise commonplace romantic melodrama.

For example, following the naturalistic opening sequence, Lang cuts to a passenger train as it slowly moves out of frame. Lang’s camera set-up, the panoramic scene visually reveals that the approaching woman, soon to be revealed as Mae Doyle, is not only a traveler; but she is also struggling with some heavy problems, for which the heavy suitcase, her baggage, is an elegant metaphor. Regardless of what she might hope to find in the fishing village ahead, confusion and a complex future, represented by the complex shapes and buildings in the distance, are waiting her arrival. Later, she crosses a cluttered rail yard and waits momentarily for a locomotive to pass. The rail yard symbolizes the cluttered road she has traveled, the troubled and difficult life she has lived, while the locomotive both foreshadows and symbolizes Earl Pfeiffer, the powerful force that she will soon meet.

Lang continues with this poetic imagery as Mae arrives at a house, her baggage in tow. She climbs some steps, Lang’s symbol for the obstacles life often places in our path, gains the front porch and through a central picture window, peers inside. The house, the warmth of hearth and home, are Lang’s symbol for happiness and peace. Mae is still just an outside observer and her failed search for the door key reveals symbolically that her search for happiness remains unfulfilled and unfinished.

Similarly, later in the movie during Mae’s odd marriage proposal scene, while she stands on the front porch, Jerry remains standing in the street below Mae as she speaks down to him. Jerry, I don’t want you to say anything now but if you still want to marry me, I’d try being the kind of a wife you need. I’d try to make you happy, if you still want me. With the emotionless voice of a woman resigned, she proposes to Jerry from a distance so that he cannot embrace her, cannot kiss her, cannot touch her. Lang has revealed visually how Mae actually perceives and feels about Jerry. An odd but revealing moment, Lang has re-imagined the earlier scene in Angelo’s when Mae initially arrived and ordered a shot of brandy but had to settle for whiskey: here she settles for Jerry, a man who she actually thinks is beneath her.

During the tense, nearly violent kitchen scene, after Jerry learns of Mae’s faithlessness, the cuckold and the two lover’s quarrel violently, sending Mae into the corner of the kitchen cabinets, where she stands, facing the two men in her now contorted life. The romantic entanglement has become an actual cinematic triangle and Mae has been forced into a corner, Jerry to her right, Earl to her left. By placing Jerry on Mae’s right, Lang cleverly implies to the audience that Jerry is the right man while Earl is the wrong man; and it’s not accidental that the adultery confession occurs in the D’Amato’s kitchen, the very center and symbol of domesticity and female compliance. As Mae’s emotions spill, she angrily admits to the affair and angrily expresses her frustration with her domestic life: Mae, Mae, Mae. Wash my face, Mae. Comb my hair, Mae. Be my cook, nurse, accountant, bottle washer. She also admits that the fault rests with her, not with Jerry. I’ve got nothing to blame you for, she confesses to him, then adds; It’s me, me, something in me. As this tense, almost violent scene comes to an end, Lang introduces the alarm clock: Jerry, who was once asleep, is now fully and angrily awake. He now perceives his wife and her paramour as uncaged animals that can hurt people.

When Jerry admits to Mae, early in the movie, that he has fallen in love with her, she concludes that Jerry wants to marry her (he never actually proposes) but dismisses the idea as silly and wrong. Although Jerry disagrees, Mae admits: I wouldn’t make a good wife for you. I’m one of those women who are never satisfied. That being the case, why does Mae change her mind and propose to Jerry? Her admission that it would be nice, married to someone like Jerry, with whom she would be safe, a man who could give her a place to rest, a man who doesn’t have a mean thought in his head and doesn’t hate women, does not completely explain her change of heart. Does desperation make it easy for her to ignore her admission: I’d be bad for you. Believe me, somehow I’d hurt you. She correctly advises Jerry: Find yourself someone who likes pushing a baby carriage and shopping and changing the curtains on the window. Her change of heart happens after her ugly encounter with Earl in the beach side bar. She knew then that Earl was the wrong man; but as harsh as their interaction was, Mae’s attraction to Earl remained unabated, her attraction to what Peggy called his energy, fifties code for his powerful sexuality. Mae even tells Earl: You impress me as a man who needs a new suit of clothes or a new love affair. But he doesn’t know which. While Earl generates a powerful desire in Mae, he also generates a powerful fear. She fears Earl’s anger, his misogyny and his narcissism. Her desire to escape, to get away from Earl motivates her rather left-handed marriage proposal, her businesslike agreement to marry Jerry if he still wants to marry her.

Before her unromantic marriage proposal, Mae assessed Earl thusly: I’m fed up with Earl … He’s fine for a ride on a roller coaster, but I’m tired of roller coasters. But is she telling the truth; is she really fed up, really tired of roller coasters? Or, had Mae already concluded that Earl would be fine for a sexual thrill, a ride on a roller coaster, even if she married Jerry. No doubt. Unfortunately, though, Jerry did not hear what amounts to Mae’s confession. Certainly, a woman as intelligent and worldly as Mae knew that a man as ingenuous and as trusting as Jerry would interpret try to make you happy as will make you happy and certainly Mae knew Jerry would expect adherence to their wedding vows, forsaking all others till death do they part. I suggest that Mae never intended to be faithful to Jerry and I offer as proof, Mae’s admission to Earl when she realizes that she’s made a mistake and that she’s deceived herself all along. What she says is nothing less than confessional:

How many times have I told myself … nothing counted but me. My disappointments. My unhappiness. I married Jerry, moved into his house, used his money and had his child and yet … yet I was never his wife. You’re someone’s wife when you belong to them. I never belonged to anybody … I said to the world: this is what I am. Take me or leave me so that it was always on my terms that they had to accept me. But it was a trick. Don’t you see Earl? It was a trick to avoid the responsibility of belonging to someone.

In a less sophisticated manner than Mae, Joe posits to Peggy a similar assessment of marital commitment:

That ring on your finger; what did you put it there for, a decoration? Listen to me, blondie. The woman I marry, she don’t take me on a wait and see basis … In my book, marriage is a two-way proposition: you’re just as much responsible as I am. So that little eye is gonna roam, if what you think is Joe’s alright until something better comes along, honey you better take another street car.

Belonging to someone means making a one-hundred percent commitment, no equivocations. Joe realizes that if Peggy equivocates, then their marriage is doomed. Contained within any equivocation is an excuse for the faithlessness of husband or wife: it has the inevitability of a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is difficult to deny one’s need to maintain and difficult to relinquish one’s sense of power, sense of control and sense of freedom; but Mae realizes that she never actually committed to Jerry; she never actually married Jerry. It’s an odd paradox, relinquishing one’s self to another in order to obtain real fulfillment, something Mae never did with Jerry. As a result, adultery was easy for her. If Clash By Night presents an overarching theme, the need for total commitment in marriage is that theme.

Some reviewers excuse Mae’s adulterous behavior because she never made a declaration of everlasting love to Jerry; but if Mae had professed an everlasting love, would her adulterous behavior then be inexcusable or even unforgivable?

Along with his many symbols, metaphors and his visual poetry, Lang effectively compares and contrasts his characters: Jerry with Earl, Mae with Peggy and Mae with Earl.

A weary and cynical woman, Mae has returned home because home is where you come when you run out of places. Her circumstances have forced her to move into her deceased mother’s bedroom, a resignation to domesticity, Fritz Lang suggests, and a return to the life-style she once rejected. Peggy, on the other hand, is young: she is just twenty years old. Peggy is also fiercely independent, wants a Cadillac, a symbol of wealth, and a trailer so she can just go over the whole country seeing places, an overt expression of her desire to be free. Peggy rejects Joe’s contention that her role is to have kids; and she hasn’t married Joe because … I hate people bossing me. You marry a fella, the first thing he does is boss you. Peggy seems to be rejecting the nineteen-fifty’s post war dictum regarding a woman’s role in society: she must be a wife and a mother, a house-wife, a cook and a maid. Mae also rejected that precept once; but life has all but beaten her. For Peggy, according to Mae, miracles can still happen. For Peggy, the future awaits so her big ideas can still be realized. For Mae, her big ideas have ended with small results.

The contrasts drawn between Earl and Jerry are just as stark as the ones drawn between Mae and Peggy. Earl is complex while Jerry, even according to Earl, is a simple man. Earl is angry and dissatisfied while Jerry is happy and content. Earl trusts no one but Jerry trusts everyone. Jerry, the fisherman, who draws his living from the natural world, the sea, is to be seen, in the context of this movie, as the good and decent man while Earl, the projectionist, who makes his living with a machine that projects unrealistic fantasies, is to be seen, not necessarily as totally evil, but less inclined to goodness or decency.

Early in the movie, when Jerry and Mae are on board his fishing boat, Lang positions the camera above Mae as she descends a ladder and looks up, directly at the camera. Later, Lang employs a similar camera set-up as Earl drunkenly climbs the back stairs of the D’Amato’s home. He, too, looks up, directly at the camera. A visual analogy and statement has been made: Mae and Earl are virtually the same. Earl recognizes their sameness. You’re like me, he tells Mae; A dash of Tabasco or the meat tastes flat. Earl also seems to know that Mae is not really the wifely type. Can’t see you doing it, he says; Hanging out the family wash. Ironically, Mae did exactly that earlier in the movie as Peggy watched. Earl also bemoans his lost youth and the dreams he once had: You know, they used to call me the king fish of Buckman County. I had zip, class, pep, a future. But that was far away and long ago … I’m just a barge floating down the river. Both Earl and Mae are adrift.

Some reviewers find the movie’s ending to be unsatisfactory. Mae’s sudden reversal bewilders them. A review published in The New York Times in June of 1952 criticized the ending thusly: But her great anguish and indecision when her mate goes berserk on learning of her infidelity and her decision to beg to return to her home and child is a change of heart not easy to comprehend or accept. The preceding summarizes how most cinema pundits view Lang’s ending. For some, Mae’s decision to dump the better looking and sexier Earl for the dumpy and unsexy Jerry is just not believable. Certainly, the ending is a bit strained; but no doubt Mae’s realization that Earl really does not want her baby, Gloria, is the catalyst for her change; and even though suggests a custody battle in court, in the fifties, adultery was not dismissed as quickly as it is in today’s much more enlightened society. With a charge of adultery against Mae and no corresponding charge against Jerry, a court battle probably would not end well for Mae and her illicit lover. In the final scene, when Jerry tells Mae angrily that neither she nor Earl will be getting Gloria, he is probably more correct than Earl. Thus, I consider Mae’s reversal more than plausible if not inevitable. The connection to and the love that mothers have for their children is not easily broken or denied; and although Earl attempts to convince Mae that Gloria is a responsibility spelled T-R-A-P, just another obligation to jettison in favor of freedom, he was probably never going to succeed.

I must take issue with the 1952 New York Times. In my opinion, Mae does not actually beg to return to her home and child. She admits to a mistake; and she asks for Jerry’s forgiveness; she asks for a second chance. Remarkably enough, Jerry appears willing to give her that second chance. While some find Mae’s change of heart to be unbelievable, to me, Jerry’s apparent willingness to forgive Mae so soon after she admitted that she loved Earl is the more incredible change; but then, Jerry still loves her. Earlier, Jerry told Mae he could forget the past, but that was before she admitted to loving Earl. And too, the fisherman Mae encounters in the cabin of his boat is a wiser, less naive, a more cautious one than she married. The alarm has been sounded. He stops her from touching him, stops her from making promises she might not be able to keep. After all, the prediction by Earl that Mae will not remain faithful to Jerry, despite her protestation, has a certain validity:

Crawl back to Jerry. How long will it last? One month. Two months. And the old music in the juke box will start all over again … O Sure it will. Duties. Obligations. Responsibilities. Out the window they’ll go and you’ll be wanting me again or somebody like me.

Certainly, the bitter sweet ending handed to the audience is an untidy one, neither happy nor sad, realistically unresolved. Doubts linger after the final shot of the fishing boats heading out to sea. Despite the pain, life goes on with faith, hope, trust and forgiveness. It’s all about forgiveness. Considering the circumstances and Jerry’s new awareness, will he be able to make such an emotional investment? Well, who knows; but at least he allows Mae to take Gloria. So, if you are looking for some brightness from Fritz Lang and Clifford Odets, possibly some expression of hope, that’s it.

Hollywood legends Barbara Stanwyk and Robert Ryan deliver compelling performances as Mae Doyle and Earl Pfeiffer. Their characters are desperate persons, angry and cynical but nonetheless intelligent and self aware. Not unlike Margo Channing and Addison DeWitt in All About Eve, Mae and Earl are basically archetypes that approach caricatures; and in the hands of lesser actors, could have devolved into anguished and melodramatic cartoons. Each character is acutely exaggerated and the timber of their dialogue is just unnatural. For example, Mae tells Earl: If I ever loved a man again, I’d bear anything. He could have my teeth for watch fobs. Do most women equate sacrificing their teeth for watch fobs with true love? Barbara delivers those lines with earnest aplomb. From Earl: Take any six women, my wife included and toss them in the air. The one that sticks to the ceiling I like. I doubt that most misogynists express their dislike for women in such an oddly poetic manner. Most would probably say directly: I don’t like women. I commend both Barbara and Robert for their ability to deliver such purple dialogue with a serious composure and demeanor and with straight faces.

And then in the other corner of the love triangle is Paul Douglas, known primarily for his stage work. I’m not going to say anything critical about the way Paul portrays the ingenuous fisherman, Jerry, because it must have been a difficult role. Surely, Fritz Lang directed him; but the rather physically large thespian appears to feel uncomfortable in the simple fisherman’s skin. During the DVD commentary track, Peter Bogdanovich situates Paul’s acting skills in the never-never land of the undistinguished, neither god nor bad, simply mediocre; but then, honestly, Jerry is simply a dull character. Still, Bogdanovich praises Clash By Night as one of the stage actor’s better cinematic efforts; and at the end of the movie, he equivocates and refers to the three main actors as brilliant. Certainly a confusing equivocation.

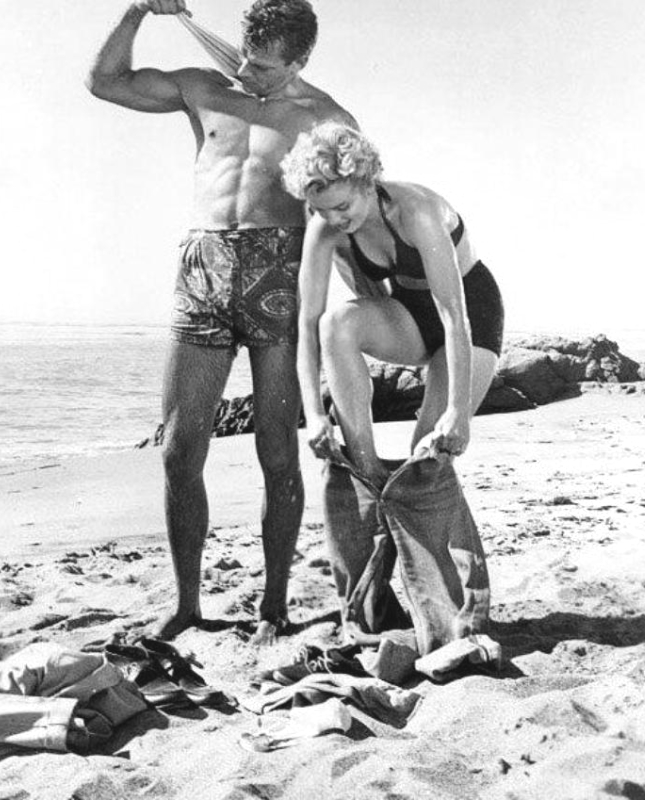

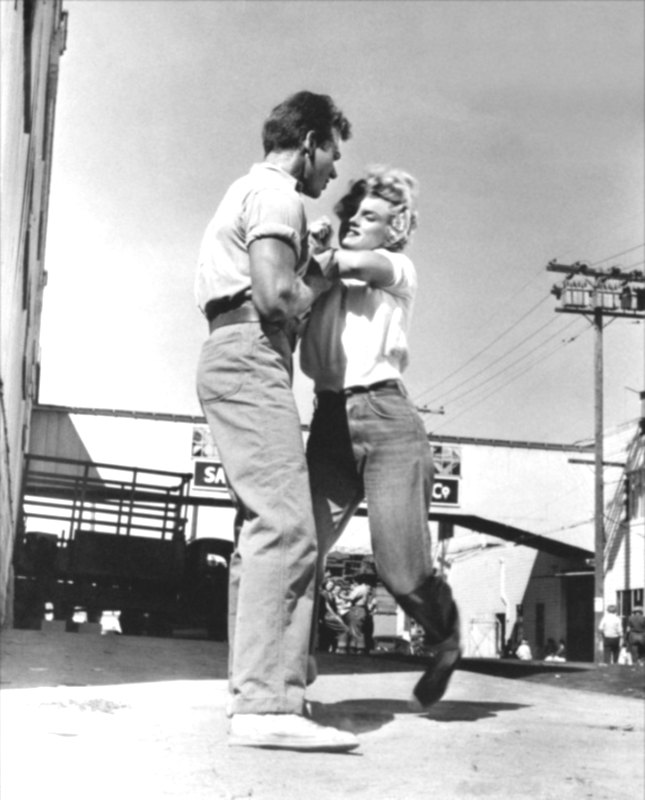

As Mae Doyle’s younger brother, Joe Doyle, Keith Andes delivers a reasonably wooden performance. He gets the opportunity on more than a few occasions to expose his well-developed, muscular body. The very embodiment of the strong but silent type, much of his on-screen time is also devoted to rough-housing with Peggy, meaning Mailyn. Fox loaned Marilyn to RKO Studios to appear in Clash By Night and once again, as she did in The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve, she made a major impression on the critics and the public. Her portrayal of the headstrong and rough Peggy is not only unaffected and, as usual, adroitly natural, she delivers a couple of good blows to Keith Andes: she’s got a rather forceful right hand. She actually smacks Andes on the jaw with her closed fist and it’s obvious that he was not expecting a real punch at that moment. His reaction is priceless, as is Marilyn’s laugh and smile.

During his DVD commentary, Peter Bogdanovich says the following about Marilyn:

Monroe never makes a wrong move. It’s amazing. Even though she’s the least accomplished actress, she doesn’t make a wrong move. It’s amazing how luminous and touching she is in everything she did in her short career … It’s interesting how Monroe pulls focus, no matter where she is, in what scene, what angle … I think Monroe is so underrated as an actress. She’s very good in this and she’s so appealing. You can see why she’d be such a big movie star, why she became such a big movie star. Even in a small part like this, she just holds the screen. She’s riveting.

Every movie in which Marilyn appeared subsequent to 1952 contained a reference of one sort or another to her nude photographs. Those 1949 stills, however mild by today’s standards, are as much a part of Marilyn’s mystique and legend as are her movies. This movie contains perhaps the first obligatory reference to Marilyn’s nudity scandal. It simply may be coincidental; but it’s only fitting, and not surprising, that Paul Douglas speaks the line that contains the reference. Jerry admonishes Uncle Vince to take down all those dirty pictures hanging on the walls in his bedroom, the ones of the women with no clothes on. Nor surprisingly, the publicity that Marilyn was receiving on set due to her revealing calendar poses particularly bothered Paul Douglas. He complained that the newspapers and magazines only wanted to interview and photograph that blonde bitch. When the producers decided to credit Marilyn Monroe above the movie’s title, the nice and convivial Mr. Douglas complained, stating that Marilyn did not deserve that recognition. It seems that Barbara Stanwyk disagreed. Not intimidated at all by Marilyn’s rising stardom, Barbara believed Marilyn should be so recognized. Bogdanovich states that Barbara and Marilyn developed a relationship during filming that he calls a friendship. However, nothing that I’ve read to date indicates that Marilyn and Barbara Stanwyk were actually friends of any sort. During the years following, Barbara admitted that Marilyn’s on-set idiosyncrasies drove her, Robert Ryan and Paul Douglas to distraction. As you have probably surmised, however, Clash By Night is remembered sixty-four years after its release primarily because of Marilyn’s few scenes.

And finally, Marilyn appeared in several movies during her Hollywood career that were dark, moody and mean, effervesced by an oddly violent and turbulent undercurrent, grimy movies. She appeared in seven to be exact, approximately twenty-five percent of her career. Oddly enough, she is usually not associated with anything other than fluff.

I’m not going to contend that Clash By Night is darker, moodier, meaner or more violent than The Asphalt Jungle, Niagara, Don’t Bother to Knock or The Misfits; but there is a certain violence in Clash By Night that sets it apart from all of the other grimy movies in which she appeared. Perhaps it’s that weird and dated, fundamentally misogynistic view of women which pervades the movie. For example, Earl expresses a desire to cut up a celluloid angel to make her look better. He wants to riddle his wife with pinholes to see if blood will run out of her and early in the movie, Joe introduces, as a subtext, a husband’s marital right to physically abuse, beat his wife. When Peggy tells Joe about a co-worker who was beaten by her husband, Joe excuses the violence with: Well, he’s her husband. Director and screenwriter never actually refute Joe’s assertion and thereby offer a tacit agreement and approval. Peggy refutes Joe’s assertion; but the movie presents her objection in a humorous, almost slapstick manner, which functions almost as a dismissal. Similarly, Jerry’s Uncle Vince states that women are spoiled, have too much education and too much freedom. He opines and even proposes that such women can only be controlled by using a whip on them: You know what I always say, horses and women, use the whip. Once again, that is presented by a slightly humorous character in a humorous manner; and not one of the men in earshot of Uncle Vince’s assertion refute it, not even Jerry. And oddly enough, Peggy agrees to marry Joe after he kicks her door down and proposes after a fight: I never thought I’d like a guy who pushed me around, she tells her future sister-in-law. Mae responds: Always take the man who’ll kick the door down. It appears as if both Lang and Odets thought that women could only be happy if they submitted to, and even encouraged, the misogyny and brutality of the men in their lives. Strange weird indeed.

Marilyn’s performance in Clash By Night, and pressure from 20th Century-Fox’s corporate offices in New York City, compelled Darryl Zanuck to screen test her for the peculiar melodrama, Don’t Bother to Knock, a movie that would offer Marilyn her first leading role as Nell Forbes.

Fritz Lang Briefly

Born in 1890 in Vienna, Fritz Lang’s career began in the era of silent movies during which he made the now revered silent movie, Metropolis, which some cinema pundits consider the first science fiction movie ever made. With a reputation as a tyrannical brute who often mistreated his cast and crew, particularly women, he was one of several Austrian-German film directors with similar reputations who fled Germany in the early 1930s, ironically, to escape Adolf Hitler, the brutality and oppression of the Nazis. Of that group, Lang was unusual. Since both Hitler and Goebbels admired Metropolis, he was offered a position in the Third Reich as head of the soon to be German propaganda studio, Universum Film AG. He declined and in 1934, moved to Paris. Unable to find any real success in the City of Lights, two years later he migrated to the City of Angels and became a naturalized American citizen. During his lengthy career, he directed movies for every major studio in Hollywood and also directed as an independent artist. Most of his efforts were crime dramas or film noir, his most famous being The Big Heat and M. It seems Clash By Night is an oddity in Lang’s filmography, a romantic melodrama, made relatively late in his career. Regarding Lang’s relationship with Marilyn, by all accounts, he was not at all understanding and did not attempt to ameliorate her anxiety or her lack of self-confidence.

Lang was the type of director who believed movies should contain a message. He often used his characters and their stories to reveal a universal meaning or truth. Experts on his movies and his life state that he was fascinated by the psychology of both men and women, along with the forces that seemingly compel them to behave, more often than not, in violently self-destructive ways. He often employed commonplace objects, like mirrors, clocks and stairs or the interplay of various shapes, as metaphors to reveal his message, amplify and clarify the action on-screen and comment on his character’s psychology. Lang was equally fascinated by humanity’s unsuccessful attempt to understand its behavior and the surrounding environment much less control either. He also believed in fate as a life shaping force.

Juxtaposing the natural landscape against the man made one of machines and industry, he often portrayed the grim landscapes in which his characters attempted to function also as powerful forces forging their lives. The naturalistic footage that opens Clash By Night is a prime example of Lang’s cinematic vocabulary even though on the DVD commentary track he suggests that he and his cinematographer, Nicholas Musuraca, shot the sequence on a lark.

Lang’s opening is unusual, particularly for a movie made in 1952. Films produced in that decade usually opened with songs or a voice-over narration setting the stage for the story to follow. Lang eschews that norm in favor of a virtually wordless opening with shots of sea birds and seals in their somewhat natural habitat, shots of heavy waves breaking against the rocky, sandy shores and shots of a dreary fishing village set against dark and cloudy, ominous skies. The opening scenes render the coastal environment and the people living in it with the realism of a documentary, black and white realism accompanied by pleasant music. The fishermen onboard the small crafts, presented at sea in a military-like formation, once anchored, unload tons of what appear to be sardines. The small fishes are then pumped onto elevator conveyors and delivered to the canning equipment of the man made world. There, they are gutted, cleaned and processed, packed into tins by the hands of women and the machines of industry. It’s grim and it’s violent but it’s also the reality of life as perceived by Lang. But then, Lang perceived chaos and violence everywhere, not only within the natural landscape but the man-made landscape and human relationships as well.