Bus Stop

31 August 1956

Marilyn Proves She Can Act

A remarkable yet strange love story, Bus Stop concerns itself with an encounter and then an odd union of two completely disparate travelers, two disparate souls, one a young cowboy, a wild and virtually unbroken stallion, the other a young but weary woman, a chanteuse who sings for and dances with the customers in a Phoenix saloon. While the quest of one is to find an angel, the quest of the other is to find some fame and fortune at the intersection of Hollywood and Vine, and hopefully, some respect as well. Oddly enough, and unexpectedly perhaps, in the end each finds, through a journey of humiliation and self-discovery and honesty, what they actually need.

Don Murray plays Beauregard Decker, a self-assured cowboy who has spent most of his life with men on a remote Montana ranch. Bo’s father surrogate, played by Arthur O’Connell, is an elder fellow, Virgil, who accompanies Bo to Phoenix for a rodeo competition. The name Virgil suggests Bo’s level of sexual experience. During their bus ride to Phoenix, Virgil suggests that Bo, now 21 years old, should consider finding himself a gal. Bo confesses that he knows absolutely nothin at all about gals. Virgil assures him that gals hain’t nothin to be a scared of. Bo decides that he will, in fact, find himself a gal but not just any old gal, mind you. Bo intends to find himself a real hootenanny of an angel. And if she resists, he declares to Virgil, gives him any trouble, she’s gonna find herself with them little ol wings just pinned right to the ground. The angel he finds, of course, and in the most unlikely of places, a rowdy saloon called the Blue Dragon Café, is Marilyn’s character, the unforgettable Cherie.

Cherie is the Blue Dragon’s chanteuse, its entertainment; and when Bo spots her singing on stage in the café, he immediately falls in love with her: he has found his angel. The café is crowded and noisy so it is difficult for Bo to hear Cherie. With blustery swagger, he quiets the crowd. Later, this act of chivalry is acknowledged by Cherie and she acquiesces to his kiss. This, along with her admitted physical attraction to Bo, signals more to the naïve and inexperienced cowboy than Cherie apparently intends: engagement and marriage and marriage regardless of how Cherie might feel about the issue. As a result, he begins to pursue her relentlessly.

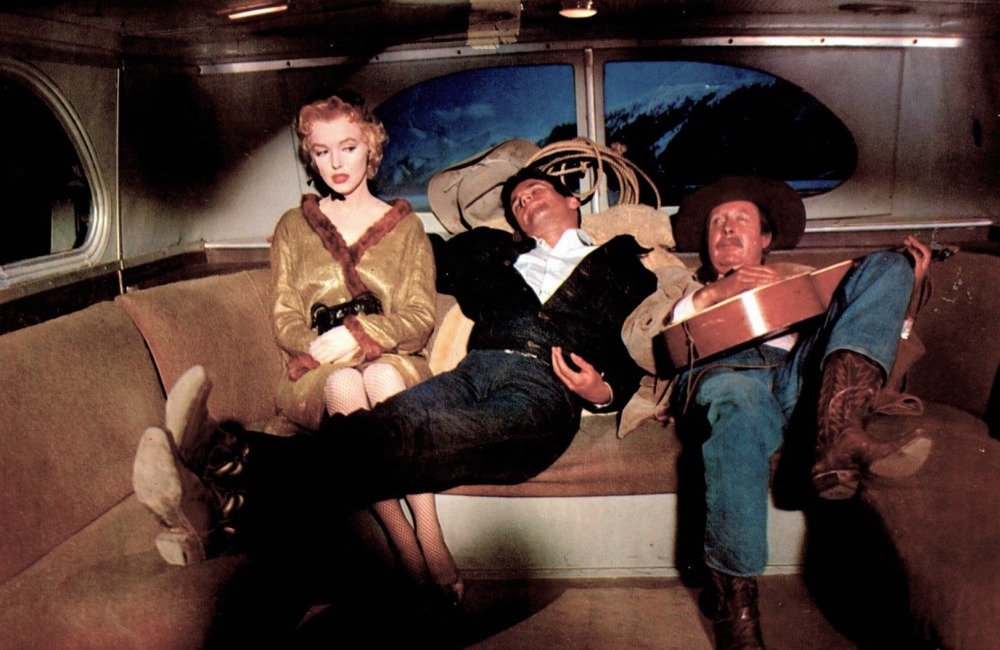

His obsession and pursuit eventually send Cherie to the bus station for an escape. While she is waiting to board a bus headed to Los Angeles, Bo arrives, produces a rope and lassos Cherie. He then forces her onto a bus headed to Montana. Bo doesn’t seem to grasp that kidnapping is against the laws of polite society, not to mention just downright rude and disrespectful. During the return trip to Montana, a serious snow storm causes an overnight delay at a roadside diner. It is during this delay that the situation really explodes and Bo’s rough treatment of Cherie causes Virgil, and Carl the bus driver, to intervene on her behalf. Bo gets belligerent which leads to a fist fight in the snow with Carl. It does not end well for Bo.

The following morning, humbled by his defeat and at the insistence of Virgil, Bo apologizes to everyone in the diner, except Carl. Apologizing to Cherie is very difficult for him because of his wounded pride but it is heartfelt and sincere. He truly regrets the awful way he treated her. I guess I been treated worse in my life, she admits. Touched by Bo’s genuine regret, his sudden vulnerability, and in an attempt to comfort him, she tells Bo that he will be better off without her: I ain’t the girl you thought I was, she tells him and is embarrassed to admit the truth. Well … I guess a lot of people’d say I led a real wicked life and I guess I have, too. She reluctantly admits that Bo is not the first man in her life. There have been quite a few others. With an opposing, but similarly embarrassing admission, Bo tells Cherie she is the first woman in his life. She agrees to let Bo kiss her but he responds with the tenderness of a charging bull. She stops him. I think this time it ought to be different, she instructs. Bo comments on how scary it is to kiss someone for real. Finally, Bo realizes that Cherie’s past is not important as long as she loves him and he loves her. I like you like you are, he tells her, so what do I care how you got that way? Cherie is once again touched and moved. That is the sweetest, tenderest thing anyone ever said to me, she tells Bo. He still wants Cherie to come back to his ranch. Why, she says, I would go anywhere in the world with you now. Anywhere at all.

Outside, as they prepare to re-board the bus, Virgil decides not to return to the ranch because Bo no longer needs a surrogate father. Bo tries to force Virgil onto the bus but Cherie intervenes and the cowboy accedes to Virgil’s decision, marking his transformation from impetuous, self-centered boy into a tender, considerate man. Realizing that Cherie is cold, Bo gives her is lined, leather coat. As he helps her slip it on and she pulls the fur collar close to her smiling face, clearly its warmth is more than gratifying and pleasurable; and when Bo steps aside, allowing her to board the bus ahead of him, she realizes that she has finally reached her destination and the end of her search: she has found respect and love. And as for Bo, maybe he has become a better man, grown and matured, maybe he has actually found an angel, albeit one with soiled wings. And we all know, as the bus leaves, that they will live happily ever after on Bo’s secluded Montana ranch, with all the cattle and all the horses and all the king’s ranch hands.

Marilyn triumphantly returned to Hollywood on February the 25th after a year-long, self-imposed exile among the literary elite in New York City: she had vanquished 20th Century-Fox Film Corporation and the mighty Darryl F. Zanuck. Although she had become the biggest star in the world and had formed her own production company with her friend and photographer, Milton Greene, the Hollywood press treated her with their usual contempt and disregard, similar to the manner with which they treated her when she announced the formation of Marilyn Monroe Productions. One female reporter even asked Marilyn if she understood the inner workings of her corporation. The press displayed only a brief interest in her new contract with Fox. One reporter wanted to know if Marilyn felt she had grown as an actress. With her usual aplomb and grace, and her usual wittiness, Marilyn patiently answered all the media’s inane and fundamentally pointless questions about her clothes, her weight and her measurements. Regarding the silly question about her growth, Marilyn answered: Well … I hardly know how to answer that since they misinterpret that, meaning in inches or something. All in attendance laughed. Regarding her contract with Fox, she admitted that she had director approval: getting the right director was extremely important to her. Her new contract with Fox gave Marilyn director approval, cinematographer approval and more artistic control over the content of her future movies. Her increased control and influence began with Bus Stop.

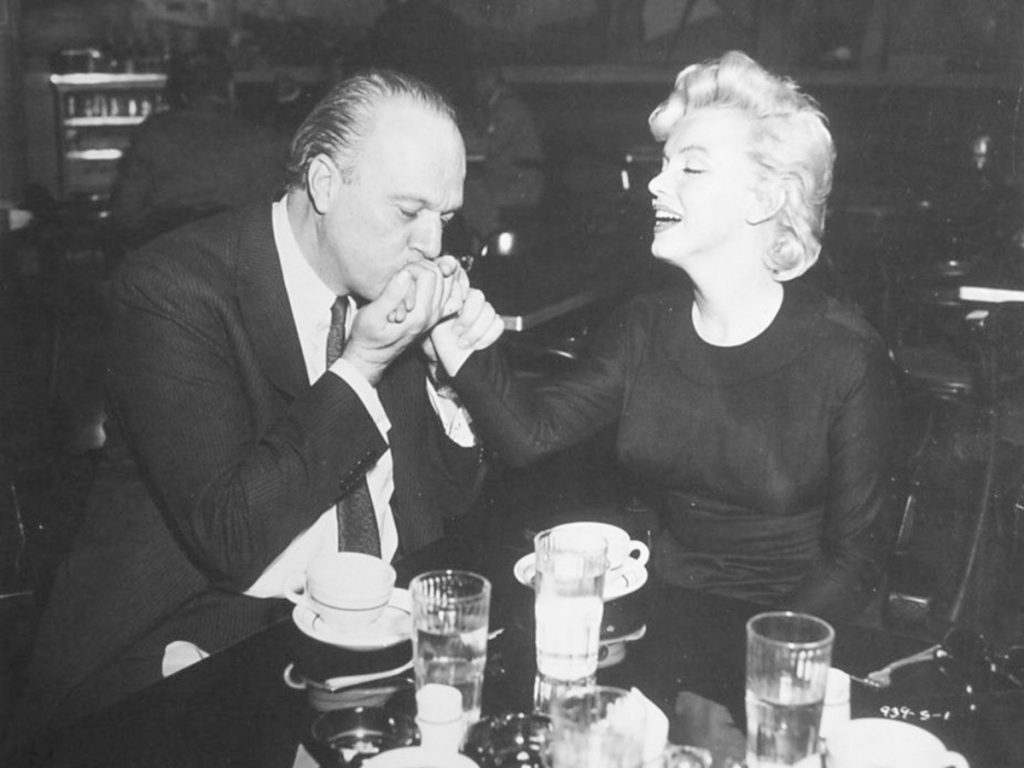

In the beginning, Marilyn wanted her director on The Asphalt Jungle, John Huston, to direct Bus Stop; but he was not available. Lew Wasserman was Joshua Logan’s agent at the time, and in order to settle an odd and tedious lawsuit involving Joshua, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and 20th Century-Fox, the agent suggested a deal whereby Joshua would agree to direct a project for MGM and direct Bus Stop, a movie to star Marilyn Monroe. The former actor, director of Picnic and Pulitzer Prize winning writer of South Pacific was reluctant to accept an assignment involving an actress who could not act: he believed Marilyn was just a sexy movie star. Marilyn Monroe, I said, Joshua later recalled, she can’t act can she? I had only seen her in these funny, flashy movies where she sort of breathed hard, was very sexy. In his memoir, Movie Stars, Real People, and Me, Joshua began a chapter dedicated to Bus Stop and Marilyn thusly: I nearly missed one of the high spots of my directing life because I had fallen for the popular Hollywood prejudice about Marilyn Monroe (Logan 42).

During the time he directed Susan Strasberg in Picnic, Joshua became friends with Lee and Paula Strasberg, but primarily Paula. After a conversation with Lee, also Marilyn’s friend, devoted teacher and method acting mentor, Joshua changed his mind. Fortunately, Wasserman informed his client, you happen to be one of the six directors she has agreed to work with. I won’t tell you which number you were on her list (Logan 44). Unquestionably, John Huston’s unavailability was a fortuitous circumstance: Joshua Logan, as things turned out, was the ideal director for Bus Stop and the ideal director for Marilyn. Since he was a former student of Konstantin Stanislavsky, Joshua accepted method acting; and as a added benefit, he also accepted Paula Strasberg.

Marilyn agreed to accept Milton Krasner as her cinematographer, since Milton had just filmed her on The Seven Year Itch and had won an Academy Award in 1954 for Three Coins in the Fountain. Marilyn had no control over the screenwriter 20th Century-Fox selected: George Axelrod. Even while he developed the adaptation of William Inge’s play, George’s most recent Broadway play, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter, was running successfully in New York City; but more about George and his play later. 20th Century-Fox Film Corporation, along with Marilyn Monroe Productions Inc., shared uncredited co-production responsibilities while Buddy Adler was the credited producer.

Bus Stop presented Marilyn with more than a few challenges, not the least of which was the importance of her performance. On prior movies, while her performances were important in a broad sense, with Bus Stop, how she handled the material, and the associated stress, would impact the success or failure of the movie, the future of Marilyn Monroe Productions and her future as an actress.

Also, a calculated risk was involved in playing Cherie, a weary, unglamorous chanteuse with little or no talent, the complete opposite of the world’s reigning sex symbol and most glamorous movie star. The executives in the offices on Pico Boulevard in Hollywood expressed their concern; they wondered if they had made a serious mistake as they watched the world’s most famous movie star, who they considered to be their own personal creation, completely deconstructed by an artistically involved and free Marilyn Monroe. She accepted Milton Greene’s suggestion regarding her make-up. A saloon singer would seldom be exposed to sunlight, he reasoned correctly; so Whitey Snyder, her personal make-up artist, developed a thick and unflattering chalky make-up, Cherie’s paleness made even more pronounced by the color of her oft disheveled curls.

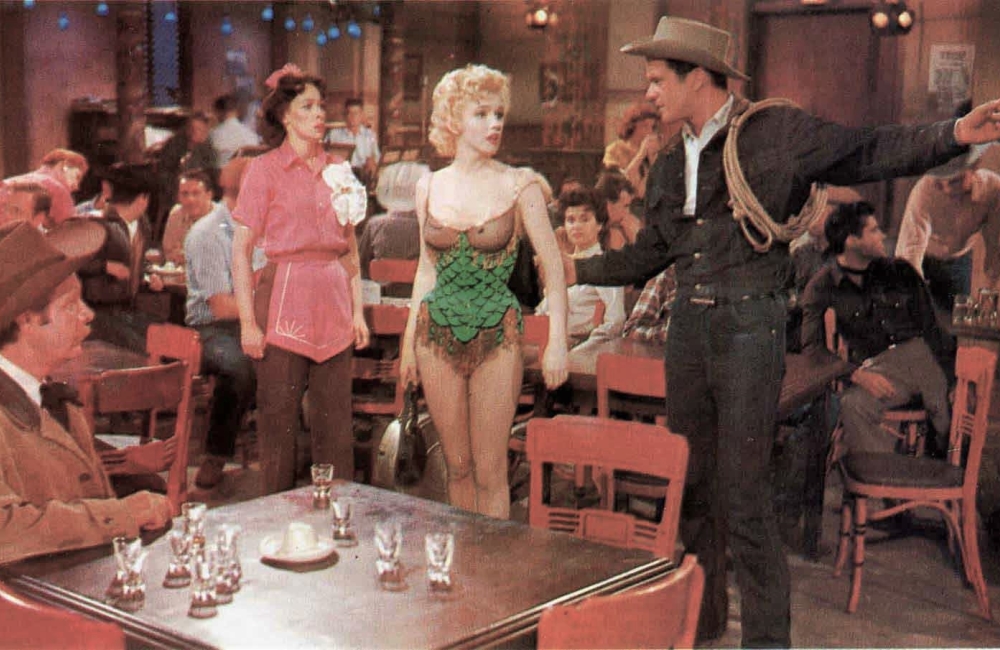

William Travilla designed some glamorous costumes, including a beautiful gown for Cherie’s on-stage musical performance; and even though she approved Travilla’s design, she planned to transform it into the type of threadbare costume an impoverished saloon singer would be forced to wear. She poked several holes into the costume’s fishnet stockings, which were then clumsily darned by the wardrobe department according to Marilyn’s instructions. Travilla’s beautiful gown became a beat-up, tattered and worn mermaid’s costume with a tail and punctured fishnet stockings. Marilyn’s fealty to realism would not be denied.

To all the expectations and concern, add that Marilyn had to maintain a consistent and believable Arkansan Hillbilly accent, deliver a completely horrible but convincing singing performance and effectively display a range of emotions: joy, anger, fear, frustration, sympathy and sadness, just to mention a few. She also had to appear alluring and sexy, innocent, wise, dumb, repulsed, certain, confused, affectionate, forgiving, disappointed and content. And if that wasn’t enough, she had to portray all the various emotions and existential states against a cartoonesque performance by her leading man.

Born in Hollywood but reared in East Rockaway, New York, Don Murray admitted in subsequent interviews that he knew absolutely nothing about cowboys and certainly did not know how to play one. He could not even ride a horse; so he played the cowboy character according to his director’s instructions. Joshua directed him, Don claimed, to act like Attila the Hun; so that is exactly what he did, created a caricature of a brash, strident, noisy, uncouth, naïve and overly self-confident cowboy never before off the ranch and with no experience at all with women. Joshua advised Don that the Bo he wanted, in fact, saw little difference between livestock and women, both were something to be roped, branded and drug home to the ranch.

Don Murray’s portrayal of Bo Decker, directed or not, initially disappointed me. His performance was just too ludicrous, too cartoonesque to be taken seriously. However, after many subsequent viewings, my opinion of Murray’s noisy and wild antics has softened somewhat. I cannot say that I enjoy his stridence, but I appreciate certain parts of his performance. For the movie to be successful as a comedy, I admit, Bo had to display near fits of churlish behavior and naïve braggadocio.

Additionally, Joshua wanted Don’s animated portrayal of the deeply tanned, healthy cowboy with coal black hair to be contrapuntal to Marilyn’s restrained portrayal of the confused young woman with a bar room pallor, crimson lips and strawberry blonde curls. While Don’s performance interferes somewhat with Marilyn’s, in my opinion, their juxtaposition works; and Bo is frequently funny. And, in the end, I must also admit, after Bo has been beaten into submission and humility, Don is allowed to actually act, to reveal and transmit a boyish charm previously hidden by Bo’s obnoxious naiveté. While the cowboy remains uncouth, we believe he is being sincere and thus we accept his transformation; we believe that Cherie just might follow him anywhere.

Also born in Hollywood and reared there as well, Marilyn was intimately familiar with the character of Cherie and her performance is proof thereof. As ambivalent as I might still be about Don Murray’s performance, I am not ambivalent at all about Marilyn’s portrayal of the sweet but mistreated chantooeuse. It is nearly flawless. Marilyn delivers an appropriate, unwavering Arkansan Ozark accent, all the requisite emotions; and she invests Cherie with a childlike innocence that doesn’t conceal her mature sexuality or her unabated ambition. In scene after scene, Marilyn shines and enthralls.

Arguably, one of her most demanding scenes must have been her on-stage singing performance. In the end, Cherie just might complete her journey to Hollywood and Vine; but she will never be discovered by fortune or fame, for she is as talentless as she is ambitious. Marilyn delivers a vocal performance that is brilliantly bad, complete with humorously trite and stale hand gestures. Her performance in Cherie’s threadbare mermaid’s costume, a metaphor for her existence, is, in its own special way, as dazzling and mesmerizing, somehow even as polished, as any theretofore delivered by Marilyn. Only a heartless lout could watch Cherie’s terrible but emotional rendition of “That Old Black Magic” as she tugs at her full length gloves to keep them up and operates the colored spot lights with her feet, exposed before the loud and disinterested crowd of beer drinkers and hell raisers, and not be deeply touched. Marilyn gives her heart and her soul, invests all her feelings and all the childlike sincerity she possesses in Cherie’s song. And yet, as she leaves the stage, not one person, other than Bo, applauds. Art, once again, imitates life.

But the scene in which Marilyn displays her skill, perhaps her genius, the long bus ride back to Bo’s Montana ranch, features Cherie’s conversation with Elma and another song of sorts: Cherie’s soliloquy. It is during this delicate scene that Marilyn invests Cherie with pathos and strength. She confesses and yet she demands. Maybe I don’t know what love is, she confesses to Elma, then declares:

I want a guy I can look up to and admire. But I don’t want him to browbeat me. I want a guy who’ll be sweet with me. But I don’t want him to baby me, either. I just gotta feel that whoever I marry has some real regard for me, aside from all that lovin’ stuff.

As Donald Spoto observed:

But it is in her long speech on the bus that Marilyn gave shape and substance to the character, somehow reaching into herself with a wistfulness that never seems self-indulgent: the character’s hopes collide with her fragility in one of the great performances of the decade. In a voice poised between tremulous confession and a great ache of longing, she spoke of Marilyn as well as of Cherie, and this gave her the truth she so immediately conveyed (Spoto 357).

Some reviewers and commentators express consternation that Marilyn chose Bus Stop as her first role after she founded Marilyn Monroe Productions and had control over her projects. She chose the part of Cherie, they contend, because Marilyn was not quite brave enough just yet to play against type. There may be some truth to their contention; and her next selected role of showgirl Elsie Marina in The Prince and the Showgirl adds some weight to their assessment of Marilyn’s trepidation.

Certainly by 1956, Marilyn was committed to casting aside the dumb-blonde-sex-symbol persona that she had created for herself, embraced and played flawlessly, a persona also embraced by what some label the Cult of Celebrity. Travis Wagner observed that Marilyn deconstructed that persona in 1955 during her seven-year-itch performance: Marilyn rejected everything that the cult of celebrity had created for her, according to Mr. Wagner. If Norma Jeane believed she had to completely dismantle her Marilyn Monroe persona in order to escape it, then any deconstruction she began on the sets of The Seven Year Itch she continued on the sets of Bus Stop.

Cherie may be a variation of the dumb-blonde-sex-symbol characters that Marilyn was forced to play during the majority of her career; but Cherie is not Pola or Lorelei Lee, and she certainly is not TheGirl. Those women probably never experienced the intractable disregard, the cruelty that men often display towards impoverished women who they believe are of easy virtue and naturally willing because of their difficult and sad circumstances. Cherie certainly experienced it, as Norma Jeane certainly did; and she certainly sustained the type of damage that flesh and blood women often do at the hands of baboons and gorillas, as Norma Jeane certainly did. Yet, neither the irrepressible Cherie, nor the irrepressible Norma Jeane, surrendered to past disappointments and fears. Neither surrendered their dreams. In some specific regards, Marilyn chose a role against type but just not completely out of her comfort zone. Unfortunately, Norma Jeane would never completely escape the gravity of her brilliant persona. To her, at times, it must have felt like a black hole.

Cinema experts and pundits assert and mostly agree that in rendering Cherie, Marilyn, the actress, rendered her best performance and that Bus Stop was her best movie. I could argue their assertion but here is not the time or the place. Bus Stop was the movie that putatively proved to all Marilyn’s critics, all her detractors and the cynics, that Marilyn was a real actress, as if she hadn’t proven that already. Bosley Crowther intoned through his typewriter from the offices of the New York Times, obviously high above the humanity filling the streets of New York City and even higher above the ignominious pretender actress, Marilyn Monroe:

HOLD onto your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress in “Bus Stop” … For the striking fact is that Mr. Logan has got her to do a great deal more than wiggle and pout and pop her big eyes and play the synthetic vamp in this film. He has got her to be the beat-up B-girl of Mr. Inge’s play, even down to the Ozark accent and the look of pellagra about her skin.

Don’t ask me why cause I don’t know why Bosley Crowther disliked Marilyn as much as he apparently did; but the man obviously had a goofy axe to grind. Maybe his dislike for American Cinema tainted his perception of Marilyn Monroe or maybe it was simply her beauty; but for the amazing performance delivered by Marilyn to be so glibly described, almost dismissed as something created by Joshua Logan, reveals much more about Mr. Crowther than it does about Marilyn’s ability as an actress: he was not a nice man. Still, The Saturday Review of Literature commented that Marilyn effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamour personality; and Joshua Logan, hesitant and dubious initially became her adoring director and proclaimed Marilyn

one of the great talents of all time, and the most talented motion picture actress of her day … I’d say she was the greatest artist I ever worked with in my entire career … Hollywood shamefully wasted her, hasn’t given the girl a chance. She has immense subtlety, but she is a frightened girl, terrified of the whole filmmaking process and self-critical to the point of an inferiority complex.

Marilyn could not attend the premiere of Bus Stop. She was in England, struggling with Sir Laurence Olivier to make The Prince and the Showgirl. Even though Joshua Logan counseled Sir Laurence regarding the way to direct and treat Marilyn, as did Lee Strasberg, Olivier would ignore their advice. Likewise, Hollywood and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences ignored Marilyn on Oscar night. For his performance as Bo Decker, Don Murray was nominated for Best Supporting Actor. Weird, considering he was Marilyn’s leading man. Marilyn’s compelling performance was not acknowledged. While she must have felt like she was being ridiculed by the town she once called a large varicose vein, once again, life just imitated art, and once again, Cherie was ignored on stage. She left unappreciated and unapplauded.