Section 1

August the 4th in 1962

Sixty two years have come and gone since Marilyn Monroe, on the date written above, immediately preceding this sentence, quite unexpectedly shufflel’d off this mortall coile. Just two months past her thirty-sixth birthday, she died alone in her small and cluttered bedroom in the house she had recently purchased and occupied at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive, one of the numbered streets named Helena, a blind and narrow street in the nice, comfortable Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. Tiny by movie star standards, 12305 Fifth Helena was the first house Marilyn could actually call her own. Prior to purchasing her tiny hacienda, she had usually lived in hotel suites or apartments, more than a few of them small and spartan. Briefly, she and Joe DiMaggio once subleased and shared a house together in the Hollywood Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles; but by all accounts, Marilyn was very excited about being a first time homeowner, and she was proud of her modest Spanish styled hacienda.

Behind the tall brick wall and dense foliage that girdled her property, she had already undertaken its renovation and remodeling, made necessary primarily by the house’s age. Built in 1929, prior to the advent of many modern appliances and other work saving machines, the modest house, with its swimming pool and red tile roof, adobe and Spanish influences, was already thirty-three years old in August of 1962.

The activities with which Marilyn occupied herself, and the circumstances surrounding the last day of her physical life here on Earth, cannot be recounted, apparently, with any certitude; so the narratives thereof vary with biographer, memoir or testimony. Even those who were actually present on that day offered contradictory testimony to the day’s events over the years following; but suffice it to say, August the 4th was a busy day for Marilyn. She was visited by friends and associates from the world of movies and photography; and her day was loaded with telephone calls.

Around 8:00 AM, just as a local greenhouse delivered a truck load of shrubberies and flowers, Eunice Murray, Marilyn’s housekeeper, arrived for work, delivered to 12305 by the auto mechanic servicing her 1947 Dodge Coronet. Norman Jefferies, Mrs. Murray’s son-in-law and also a handy man recently employed by Marilyn, arrived shortly thereafter, entered Marilyn’s kitchen, spoke to his mother-in-law and then continued his efforts restoring the kitchen flooring. Around 9:00 AM, Marilyn appeared in the kitchen wearing her white terrycloth bathrobe or possibly wrapped in a large white bath towel; and as Marilyn stood at the open refrigerator, she poured and then drank a glass of grapefruit juice. She then took a telephone call from Ralph Roberts, her close friend and masseur: they talked about their plans for a Sunday evening BBQ. After dressing in her bedroom, Marilyn walked outside.1Apparently there is some confusion over how to correctly spell Norman’s last name. Several biographers spelled the name Jeffries and several spelled it Jefferies. I merely chose to employ the latter spelling.

Lawrence Schiller, a photographer who had recently photographed Marilyn swimming partially and completely nude on the set of Something’s Got to Give, recounted in his memoir, Marilyn & Me, that he arrived at 12305 around 9:30 AM with some photographs for her to evaluate. For his 1993 Marilyn biography, Donald Spoto interviewed the slightly arrogant photographer. During his interview with Spoto, Schiller testified that he arrived at 12305 Fifth Helena and found Marilyn tending a flower bed in front of the house, that she appeared to be refreshed and alert and seemingly without a care (Spoto 566). However, virtually two decades later, on the pages of his 2012 memoir, Schiller contradicted what he described for Spoto. According to the photographer’s memoir, his famous subject was dressed casually and kneeling in a flower bed when he arrived. She stood and approached; she was slightly disheveled; her hair was unruly; and she was sans makeup. In Schiller’s opinion, the woman who approached him would never have been mistaken for the world’s sex symbol: You’d never know it was Marilyn Monroe, he wrote. She didn’t look like any of the pictures that I had taken (Schiller 94). And too, she was cross impatient unfriendly. After a brief but tense conversation with Marilyn, Schiller handed her his photographs and departed.

Around noon, Pat Newcomb, Marilyn’s press agent, publicist and close friend, got out of bed. Pat had spent the night with Marilyn after the two women allegedly dined out the night before. She dressed and made her way outside where Mrs. Murray served her lunch. Not long after 1:00 PM, Marilyn’s psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, arrived for the first part of a two part therapy session. As noted later by Marilyn’s attorney and Dr. Greenson’s brother-in-law, Milton Rudin, the psychiatrist ended up spending most of that Saturday with Marilyn. While the actress and her therapist talked in private, Pat lounged by her host’s swimming pool under the Southern California sun.

Apparently around this time, Joe DiMaggio, Jr. placed his first of two unsuccessful collect telephone calls to his former stepmother. Mrs. Murray answered the telephone and simply informed the operator that Marilyn was not at home. Shortly after 3:00 PM, Dr. Greenson emerged from his session with Marilyn. He asked Pat to leave: Marilyn was upset with her acknowledged best girlfriend. The psychiatrist never revealed why Marilyn was upset with her overnight guest; but most accept this assertion by Pat as reported in Spoto’s biographical account: Marilyn was tense and angered because Pat had slept through the night while Marilyn, who suffered from chronic insomnia, had managed only a few hours of fitful sleep (Spoto 566). Anger over Pat Newcomb’s ability to sleep seems more than petty, something unusual for Marilyn; but Lawrence Schiller provides another possible reason why Marilyn was upset with Pat.

At the time, Schiller was negotiating with Hugh Hefner for a front and rear cover featuring a partially unclothed Marilyn Monroe to mark the tenth anniversary of her appearance in the inaugural edition of Playboy. The photographs Schiller delivered to Marilyn depicted her both partially and completely nude, taken during and after the swimming pool scene from Something’s Got to Give. The photographer hoped Marilyn would approve them and release their use by Hefner in the near future. Apparently, though, Pat Newcomb objected to Marilyn’s possible second appearance in Hefner’s Playboy. During a telephone call from Pat the previous evening, the press agent had voiced her objections to Schiller; and the photographer quoted Pat’s objections to Marilyn, reiterated Pat’s opposition to what Schiller and Hefner had planned for Marilyn. Pat feared that Marilyn would simply be adding to the many problems she already had by appearing even partially nude in Playboy. When Schiller told Marilyn on the morning of August the 4th about Pat’s telephone call, the actress tersely commented, according to Schiller, that Pat did not have the authority to call him or to make such a statement. Schiller asked if he needed to have another conversation with Pat on the following Monday. His subject allegedly replied: It’s still about nudity. Is that all I’m good for? I’d like to show that I can get publicity without using my ass or getting fired from a picture (Schiller 93). She had yet to decide about appearing in Playboy, she told Schiller; she would apprise him of her decision with a telephone call. It seems plausible to contend that Marilyn was upset with her publicist for interfering without authority. Also, she was obviously disgruntled with her continued sexual exploitation and her contractual difficulties with 20th Century-Fox Film Corporation.

Fox had terminated her in June for what the studio claimed was her substandard acting on Something’s Got to Give; and even though she believed she had received permission from the studio to appear at John Kennedy’s 1962 birthday gala the previous May, the studio contradicted her and called her appearance at Madison Square Garden a defiant act, indicating Marilyn’s obstinate nature and reluctance to cooperate. Although Fox had fundamentally rehired her in July, the requisite contracts awaited signatures, which possibly left Marilyn ambivalent about the photographs, ambivalent about agreeing to appear in Playboy even partially nude at such a sensitive time in her movie career.

Automobile mechanic, Henry D’Antonio, along with his wife, delivered Eunice’s Coronet to Fifth Helena not long after Pat Newcomb had departed; and before Dr. Greenson departed, he used the delivery of Eunice’s car to suggest that a beach walk might help Marilyn relax; so Eunice drove her to Santa Monica Beach near Peter Lawford’s beach house, and upon leaving her there, proceeded to the grocery store.

While waiting for Eunice to return from grocery shopping, Marilyn strolled along the beach and also observed a volleyball match. According to Donald Spoto, William Asher, who was a director employed by Peter Lawford’s production company and also directed John Kennedy’s birthday gala, recalled that Marilyn visited Santa Monica Beach around 3:00 PM on August the 4th in 1962. I was there, he informed Spoto, along with a few other people who had dropped by, when Marilyn arrived and took a walk on the beach (Spoto 567). After Eunice completed her shopping, she collected Marilyn and they returned to Fifth Helena, arriving there between 4:15 and 4:30 PM.

Slightly after 4:30 PM, the junior DiMaggio telephoned again; but his collect call was intercepted once again by Mrs. Murray. Once again, she lied to the operator and said that Marilyn was not home. Shortly thereafter, according to Dr. Greenson’s admission in a letter he wrote on August the 20th to Marilyn’s former therapist, Marianne Kris, he returned to Fifth Helena Drive to continue his therapy session with Marilyn. Before continuing with Dr. Greenson, and before Mrs. Murray could, Marilyn answered the ringing telephone around 5:00 PM. Peter Lawford invited Marilyn to join him and his guests for a casual dinner party at his beach house; but Lawford’s wife, Marilyn’s close friend and a Kennedy daughter, Patricia, was out of town; so Marilyn declined, opting instead to continue her session with Dr. Greenson. Several biographers and Marilyn historians have asserted that Marilyn actually neither liked Peter Lawford nor trusted his intentions.

At approximately 5:30 PM, Marilyn’s former father-in-law, Isadore Miller, telephoned; but he did not speak with Marilyn. Mrs. Murray told Isadore that she would have Marilyn return his call. About fifteen minutes later, Ralph Roberts telephoned a second time to discuss the menu for their planned Sunday evening BBQ. Roberts reported in an interview with Donald Spoto that Dr. Greenson answered the telephone; and when Roberts asked for Marilyn, the doctor simply replied that she was not there and then immediately hung up. After he obviously and mysteriously lied to Ralph Roberts, Dr. Greenson continued with Marilyn. Their therapy session ended between 6:45 and 7:00 PM. Soon thereafter, at approximately 7:15 PM, Dr. Greenson, who had an engagement for the evening, departed but not before asking Mrs. Murray to spend the night at Fifth Helena: apparently the doctor was concerned about his patient’s emotional condition and her frame of mind. Marilyn never returned Isadore Miller’s telephone call.

A mild and soft Saturday evening spread itself over Los Angeles and Southern California like sheer bedclothes as sunset floated across North America. At approximately 7:20 PM, Marilyn finally spoke with her former stepson. Their conversation was a brief one. He told Marilyn that he intended to follow her advice: he was not going to marry his girlfriend, which pleased his former stepmother. She believed that Joe Junior was too young to marry. Not long after her conversation with the junior DiMaggio ended, Marilyn telephoned and reported the good news to Dr. Greenson. That was the last conversation the psychiatrist would have with his most famous patient.

Slightly after 7:30 PM, Marilyn advised Mrs. Murray that she was going to bed; but before doing so, she took a second telephone call from Peter Lawford. He still hoped that Marilyn would attend his dinner party. She informed Lawford that she was tired and she was going to bed: she planned to read.

Marilyn and Eunice were alone in the house on Fifth Helena Drive as the world’s most famous woman entered her small and cluttered, sparsely furnished bedroom and closed the door, a commonplace act that on August the 4th in 1962 not only signified the end of Marilyn’s active day, but also the end of Marilyn’s time on Planet Earth, more accurately stated, that is, her time physically. The fiery ball at the center of our solar system, by then a hazy red disc, fell below the earth’s rim far beyond the Pacific Ocean at 7:51 PM. Twilight lingered for an hour and a half in the cool damp air then faded as the night fell on Marilyn’s hacienda at 9:26 PM. Soon, a night of sorts would befall the world as well: its brightest star was never again seen alive, her brightly exploding image thereafter relegated to a projection, white, very bright light forced through celluloid.

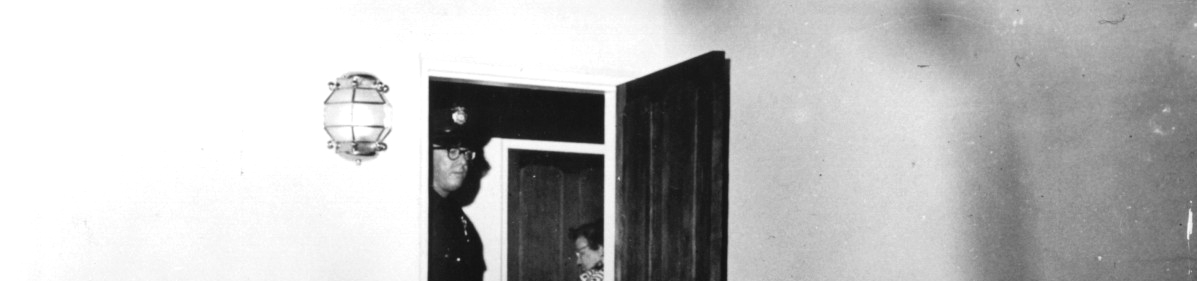

Sometime later, Eunice Murray discovered Marilyn’s body; but the exact mechanism that alerted Eunice, causing her to thereby became concerned about Marilyn’s welfare, remains uncertain, even hotly debated. The exact time that Eunice telephoned Dr. Greenson and then on his instructions, took a fireplace poker outside and pushed aside the fabric draping an open bedroom window, the exact time she peered inside, also remains hotly debated. But when Eunice peered through that bedroom window past the parted drape, she saw Marilyn’s lifeless and unwrapped body lying face down across her bed. Her body had already assumed the stiffness of death and its darkened hue.

I created the preceding account of Marilyn’s final day alive using selected details lifted from selected biographies and memoirs. If I was so inclined, I could create a completely different chain of events leading to Marilyn’s entry into her bedroom, a completely different final day scenario. Jay Margolis and Richard Buskin, for example, in their case closing literary effort, reported that Ralph Roberts gave Marilyn her regular Saturday massage between 9:00 AM and 10:15 AM, before leaving by the front door, completely unnoticed, apparently. Carl Rollyson cited Ralph Robert’s presence along with Marilyn’s massage; but Rollyson reported that Laurence Schiller did not appear at Fifth Helena until 10:30 AM, a time which completely contradicted Schiller’s memoir. However, biographer Donald Spoto, who interviewed Marilyn’s good friend and masseur, did not mention Ralph’s presence that morning or that alleged massage. Additionally, biographer Gary Vitacco-Robles reported that Schiller arrived sometime before noon and that Marilyn took the photographer on a tour of Fifth Helena during his August the 4th visit. Vitacco-Robles also failed to mention that Marilyn received an early morning massage. Biographer Michelle Morgan mentioned a Schiller visit in her Marilyn biography; but she did not mention a tour of Fifth Helena. Donald Spoto did not mention a residential tour and neither did Schiller in his written memoir. Marilyn biographer, Randy Taraborrelli, did not mention a visit by Schiller at all. Likewise, the murder theorists Jay Margolis and Richard Buskin also excluded Schiller’s visit from their accounting of August the 4th’s events. In his memoir, Mimosa, published in 2021, Ralph Roberts did not mention an August the 4th Saturday morning massage: Ralph noted that he performed Marilyn’s final massage on Thursday night, August the 2nd, during which both Wally Cox and Marlon Brando telephoned and briefly spoke with Marilyn.

Additionally, the time that Pat Newcomb actually departed Fifth Helena has been debated since Pat indicated, during an interview, that she did not leave Marilyn’s company until 6:00 PM; and David Marshall, who wrote The DD Group: An Online Investigation Into the Death of Marilyn Monroe, along with several of his co-investigators, questioned whether Marilyn actually visited the beach on August the 4th and suggested that William Asher was merely confused regarding the actual date he observed Marilyn walking in the sand. In her memoir, Marilyn: The Last Months, Eunice Murray did not mention that frequently debated trip to Santa Monica beach.

Am I suggesting that the differences between biographical accounts are intentional misrepresentations of what actually transpired on August the 4th? No; but I believe it is imperative to understand this: the story of Marilyn’s life achieved a mythological status long ago and that mythology is a powerful magnet. It is the mythology of which many wanted, and still want, apparently, to be a part. Additionally, Marilyn’s story has been told more than just many times; and with each retelling, the testified to facts of her complex life entered the realm of biographical flexibility and the vagaries of faulty human memory.

However, I implicitly trust the assiduously researched, two volume Marilyn biography written by Gary Vitacco-Robles. I also trust Donald Spoto’s biography along with the volume published by Michelle Morgan and, to an extent, the one published by Stacy Eubank; on the other hand, I am not as trusting of Randy Taraborrelli or the photographer, Lawrence Schiller, who initially met Marilyn in April of 1960 while she was filming Let’s Make Love. He photographed her for three days but did not actually see her again for two years when he photographed her on the set of Something’s Got to Give. Still, he speaks about Marilyn as if they were intimate friends. And, too, his memoir was written for inclusion in a book of the photographs he took of Marilyn, primarily the famous swimming pool scene as she filmed her final but never completed motion picture. As a result, Schiller gave many publicity and potential sales driven interviews for his beautiful but extremely expensive coffee table book. During the course of those many interviews, he contradicted his written memoir and many of the assertions contained therein. What I believe I can trust about the testimony of Lawrence Schiller is this: he recounted the events as he remembered them at the time of each interview; and I consider it an important reflectional factor that his main goal was to sell his expensive book. With Randy Taraborrelli, I believe he began his Marilyn biography with a premise and then used all the clairvoyance at his disposal to prove it.