Journey to Immortality

1962

The Legend of a Poor Girl

Many of the years embodying Marilyn’s adult life, and her Hollywood career, began with preparations for a new movie. 1962 was no different: she began to ready herself, prepare a strategy for her thirtieth movie, Something’s Got to Give. Dr. Greenson and Marilyn dispatched Eunice Murray, now ensconced firmly in the actress’ life, to find Marilyn a house that she could make into the home she never had. Eunice recommended a Spanish style bungalow located at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles. Within walking distance of Dr. Greenson’s home, the house chosen by Mrs. Murray resembled the doctor’s. Remarkably, the doctor had actually purchased his hacienda from Eunice. She and her husband, John Murray, a carpenter, built the house in 1946. After only four months of residency in the house with his three daughters, one of which was named Marilyn, John abandoned his family. Eunice was forced to sell her house to Dr. Greenson. Afterwards, Dr. Greenson hired Eunice and placed her in the homes of various important clients to act as helper, cook, maid and the doctor’s willing spy. Such was the case with Marilyn.

As she made plans to remodel and renovate the house, Marilyn returned to Manhattan on the 1st of February to review the script of Something’s Got to Give with Paula and Lee Strasberg: she feared she had agreed to perform in yet another movie destined to fail. A nonsensical story with a mundane script, the writers couldn’t even decide how to end the silly thing. From Manhattan she traveled to Florida for a visit with Isadore Miller who had recently relocated to Miami. After a few days visiting her ex-father-in-law, she traveled South of the border, where Eunice and Pat Newcomb awaited her arrival. They shopped for some authentic Mexican furniture, pieces appropriate for Marilyn’s hacienda. They returned home on February the 20th. Joe DiMaggio arrived in Hollywood for a brief visit―and to check on Marilyn. The middle of March arrived along with a viral infection as Marilyn prepared for late April filming with Dean Martin and former dancer, Cyd Charise.

Still concerned about the movie she was about to make, Marilyn prepared as she had many times in the past. Little did she know that skullduggery and deceit was afoot, motivated primarily by Fox’s financial difficulties. The expensive and misguided production of Cleopatra in Europe had become a quagmire, complete with the very public battles and affair between Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor: Liz nearly died during filming. More problems arose for Fox as filming began on Something’s Got to Give and Marilyn missed several filming days due to sinusitis. When she was on-set, she often worked through the effects of a fever and prescription medication; but on May the 17th, believing she had permission from the studio to leave, at 11:30 AM, she boarded a helicopter with Peter Lawford and Pat Newcomb for a brief flight to the airport. Once there, all three boarded a flight to New York City. The executives at Fox, along with George Cukor, expressed incredulity that Marilyn would leave without their permission. Tempers began to flare.

On Friday, she rehearsed in her Manhattan apartment and then on Saturday evening, the 19th of May, she sang her now famous version of Happy Birthday to President John F. Kennedy. After the birthday celebration, she attended a private party at the residence of Arthur and Mathilde Krim, accompanied by Isadore Miller. She doted over her him, spoke to the president, his brother, Robert and several other stars in attendance. Mrs. Krim remembered the Marilyn of that legendary evening this way: There was a softness to her that was very appealing. She was just―well, extraordinarily beautiful (Spoto 521). She returned to California on Sunday the 20th, uncertain of what awaited her: the angry Fox executives served her with a breach of contract warning during her stay in Manhattan. Fox threatened legal action with dire consequences if she continued to delay the production of Something’s Got to Give. Marilyn was angered by Fox’s insolence, by the failure of her managers to protect her from such an outrageous claim. She was also concerned that she might actually be terminated by the studio.

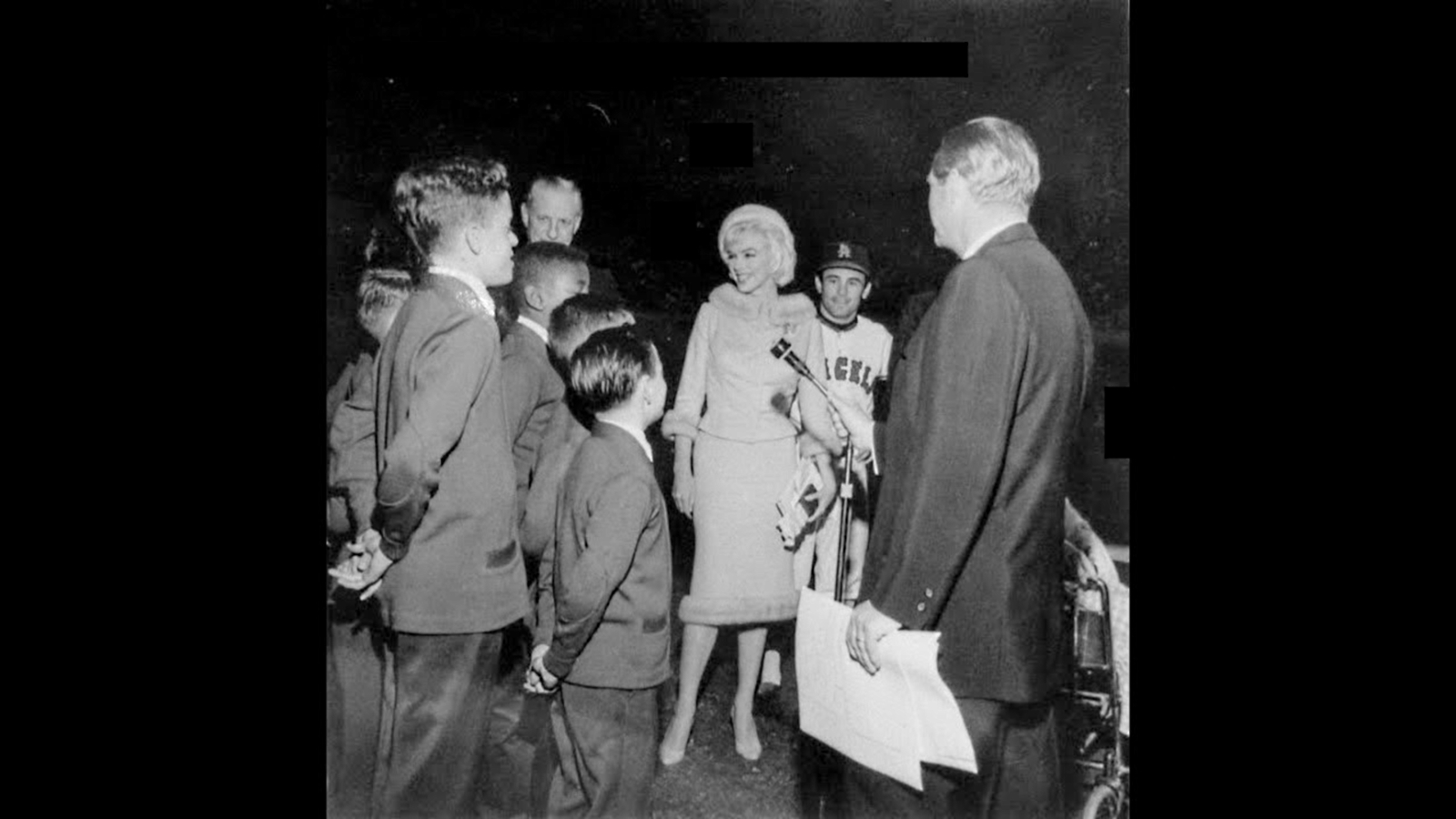

On June the 1st, along with cast and crew, George Cukor allowed her to celebrate her thirty-sixth birthday on the set of Something’s Got to Give―once she had worked a full day. After the studio party ended, she and costar, Wally Cox, attended another brief birthday celebration with Marlon Brando. Then Marilyn dressed and headed to Dodger’s Stadium with Dean Martin’s son where she threw out the first pitch, posed for photographs and spoke to the crowd about the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Her efforts on behalf of that charity in Chavez Ravine represents her final public appearance on the last birthday she would celebrate.

For her unselfishness, the cool night air of Southern California exacerbated her lingering sinus problems. She reported a fever to the studio on June the 3rd and stayed home. The studio’s physician, Lee Siegel, examined Marilyn at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive and confirmed her illness; but the executives at Fox did not believe him. Then George Cukor told the studio hierarchy that he had viewed some of Marilyn’s scenes and considered her work to be poor. After Cukor’s betrayal and act of inexplicable sabotage, Milton Gould, an attorney who was also the head of Fox’s executive committee, ordered Marilyn fired. On June the 8th, Fox filed a breach of contract suit in the amount of $500K against her personally and Marilyn Monroe Productions, effectively ending their relationship. In a subsequent, revised filing, the studio raised the amount to $750K.

The studio’s publicity department mounted a campaign to prove their decision to terminate Marilyn was the only decision they could have made. The studio accused her of constant tardiness and frequent, unexcused absences. She floated through her scenes, they claimed, and performed poorly, the result of her alcohol and drug dependency and her uncooperative and inattentive demeanor. They accused her of being deranged, possibly even insane. The executives on Pico Boulevard expected Marilyn to simply take their defamation, not to defend herself; but, yet again, they underestimated the resolve and the will power of their biggest and most popular star.

Marilyn launched a counter offensive to prove that Fox was not telling the truth about her. She posed for photographs with photographer Douglas Kirkland to verify that she was in the best physical condition of her life; and she gave interviews, proving that Fox had made a colossal and insane blunder. When the studio informed Dean Martin that they planned to hire Lee Remick as Marilyn’s replacement, he invoked his right of costar approval and informed the studio that he would not proceed without Marilyn Monroe. A newspaper headline declared: No MM. No Martin! Marilyn was gratified by and appreciated Dean’s loyalty. Fox, however, did not: the studio sued Dean for breach of contract and $3M; he counter sued them for over $6M, claiming damage to his reputation and career. Suddenly, 20th Century-Fox was embroiled in law suits while their real problem, the expensive production of Cleopatra in Europe, Liz and Richard, plodded along. Once the photographs of the nude swimming scene featured in Something’s Got to Give began to appear in the publicity magazines, generating an excitement similar to what her nude calendar photographs had generated in 1952, Marilyn’s travails with 20th Century-Fox supplanted the affair between Liz Taylor and Richard Burton as their featured story. Elizabeth Taylor all but disappeared from the magazine covers and headlines.

Little did the executives at Fox expect the reaction of Billy Wilder and Otto Preminger when they learned of Marilyn’s termination. Each said they were ready to direct Marilyn again in suitable movies. Wilder even said: I can tell you my mouth is watering to have her in another picture; and her long time adversary and nemesis, Darryl Zanuck, no longer the studio head but still a powerful player in Fox’s hierarchy, realized the major mistake that the Hollywood executives had made. He dispatched a blunt message to them in which he demanded the immediate reinstatement of Marilyn. According to Zanuck’s daughter, he was normally a fearless man, but the mishandling of Marilyn Monroe and Cleopatra, a movie he believed would be a colossal failure after viewing some raw footage, frightened Zanuck and he expressed concern for the future of 20th Century-Fox (Vitacco-Robles v2:491).

Due to the pressure applied by the public and Darryl Zanuck, Fox dropped the law suit. Surreptitiously, they began new contract negotiations with Marilyn. Eventually, Fox agreed to rehire her; she agreed to complete Something’s Got to Give and return to the Fox lots in late August. Fox increased her salary from $100K to $500K and she agreed to appear in one final Fox film for an additional fee of $500K. Fox also agreed to replace George Cukor with Jean Negulesco who directed Marilyn successfully in How to Marry a Millionaire.

The executives managing the studio at that time would not survive the debacle of Marilyn’s treatment: Darryl Zanuck soon returned to Hollywood from Europe and re-established his control. But the public’s reaction to Marilyn’s termination cannot be overlooked or underplayed. A large quantity of telegrams appeared and an equal amount of telephone calls came into the switchboard at Pico Boulevard inquiring about Marilyn’s new movie, suggesting and requesting that the studio should reinstate her. Gary Vittaco-Robles offered this analysis: Marilyn was a survivor whose resilience over came the unfortunate circumstances of her childhood, multiple traumas, depressive episodes, and numerous losses. She rose to the top of her profession as a beloved actress whose name was known from Nairobi to Tasmania. She stood up to Fox’s tyranny in 1955 and emerged the victor (Vittaco-Robles 495); and this time was no different. Once again, she had won a hard fought victory over the often intractable and imbecilic studio that treated her with staggering disregard and contempt.

In the aftermath of the Payne-Whitney debacle, Joe DiMaggio once more became the man in Marilyn’s life. Even after their brief marriage ended in 1954, Joe was never really out of or gone from her life. By some accounts, Joe was obsessed with her, as if he was the only man who ever obsessed over Marilyn. But practically all of Marilyn’s inner circle confirmed that she truly loved Joe, loved him differently than the other men in her life, including Arthur Miller. Joe was sedate and laconic, often controlling; but he never betrayed her. He was there for her when she truly needed strength and support. A few persons, friends and biographers, question whether Marilyn planned to remarry Joe, one being Marilyn’s friend James Haspiel; but two of her biographers, Donald Spoto and Gary Vitacco-Robles, have concluded, based on the overwhelming evidence and statements from both Joe and Marilyn, that they planned to remarry in the presence of a few very close friends in the garden on Fifth Helena Drive on the 8th of August. If I can only succeed in making you happy, Marilyn wrote to Joe, I will have succeeded in the biggest and most difficult thing there is. That is, to make one person completely happy. Your happiness means my happiness and … (Spoto 593). Tragically, she never finished that letter or made it to the alter with Mr. 56; and she never returned to the streets, the buildings or the sets at Pico Boulevard. Her body was discovered in her bedroom, during the small hours, the morning on August the 5th. The exact time of that terrible discovery is still debated to this day. As Sunday, August the 5th began, the media announced to the world the unbelievable news of the incredible loss: Marilyn Monroe was dead.

Marilyn’s life was always full of activity, busy busy busy, buzz buzz buzz, little bee always making honey. She was constantly in demand and wherever she went, everyone, dignitary or servant, wealthy or poor, the powerful and the powerless desired to be in her presence, to breathe the rarefied air that she did, to smell her, to touch her. People constantly reached for her like they often reach for famous politicians or religious figures. For some, I imagine, experiencing her in the flesh was exactly like a religious experience, moving and unforgettable.

She attended parties and charitable events along with the premieres of movies and the opening nights of plays. She regularly posed for photographs. Many movie directors, producers and playwrights sent her scripts and film synopses, proposals to appear in this or that movie and even to appear live on stage. Marilyn considered them all but none came to fruition. She spent a considerable amount of time in the eyes of the people to whom she felt she owed everything, her fans. I knew I belonged to the public and to the world, not because I was talented or even beautiful, but because I had never belonged to anything or anyone else, she wrote in her autobiography. If I’m a star, then the people made me a star (Monroe 159). Marilyn was the world’s biggest star and her gravitational pull was nearly irresistible; but something was otherwise missing from the center of her life. She dressed glamorously and flashed her million watt smile while waving to her many adoring and devoted fans. Norma Jeane was one convincing actress, proven by her most enduring performance, the one most often overlooked, her performance on the world’s stage as Marilyn Monroe.

The body that practically every man desired, the symbol of innocent but frisky sexuality, the ultimate feminine, lay unclaimed in the Los Angeles County Morgue for the better part of two days. Then the man who loved her like no other, needing but a white steed and a gleaming Excalibur to complete his transfiguration into a knight, arrived to claim her as he did once before, when she was entombed by the cold block walls of Payne-Whitney; but Joe could not threaten to dismantle this tomb with his bare hands and rescue her. He could not save her from this reclamation.

Yet, he did save her from the cameras of the press, saved her from the pitying gazes of the hypocrites and leeches who used her throughout her brief adult life. No one from Hollywood was allowed to attend her funeral save Whitey Snyder and Ralph Roberts, both like her brothers. Marilyn’s half-sister, Bernice Miracle, was there, as were the Strasbergs and Joe’s son. There were a few others. Twenty-five. A small number considering the magnitude of the woman to whom the world was saying good-bye. After the memorial service, after Marilyn’s body had been sealed in its final Earthly resting place, after Marilyn’s family and friends had departed, the cemetery opened to the public.

Appearing stunned and shaken, shocked by the monumental scene, many of her fans milled idly about. Some openly wept, others snapped photographs and stole souvenirs, a rose, a chrysanthemum from the many flower sprays arranged at the foot of her tiny crypt. A small, simple bronze plaque affixed to the crypt’s marble valance whispered the occupant’s name: Marilyn Monroe.

Slowly the afternoon passed into a reddened dusk. With Aunt Grace and Aunt Ana nearby, as the sun disappeared silently into the ocean, Norma Jeane and Marilyn, already in eternity, slipped silently into immortality. Jacqueline Onassis pronounced the perfect epitaph: She will go on eternally.