Mark Shaw, the President’s Birthday Gala and Marilyn's Gown

The crystal encrusted twinkly sparkly gown Marilyn wore, when she intoned her sultry rendition of “Happy Birthday to You” for President John Kennedy at Madison Square Garden―along with her version of “Thanks for the Memories”―has now been enshrined by Ripley’s Believe It or Not. I know that is difficult to believe. Sold at auction for more than $5M, including auction fees and buyer’s premium, the number of tall tales told about that gown rival the number of tall tales told about that Manhattan evening.

For example, in their publication, Marilyn—The Last Take, writers Peter Brown and Patte Barham alleged that Marilyn arrived at MSG that night with her hair still in curlers. Their source for that tidbit of history? Hair stylist Mickey Song, who the authors asserted actually styled Marilyn’s hair that night after she arrived, actually created that dynamic right-hand flip. According to Brown and Barham, Song also overheard an argument between Marilyn and Robert Kennedy during the attorney general’s visit with the actress backstage in her dressing room. Allegedly, upon departing the dressing room, the attorney general called Marilyn a rude bitch―that is, according to Mickey Song according to Brown and Barham. However, in a 1998 interview with Marilyn biographer, Gary Vitacco-Robles, Mickey Song disavowed that story: according to the hairstylist, he never made those statements, neither witnessed Robert Kennedy backstage nor overheard an argument; Mickey Song accused Brown and Barham of fabricating his testimony (Vitacco-Robles KEv2:25). Imagine that!

Actually, Kenneth Batelle styled Marilyn’s hair in her Manhattan apartment prior to that May 19th event, proven by an extant receipt (Vitacco-Robles KEv2:25). The cost? $75. A sum equal to approximately $675 in today’s inflated marketplace.

Those facts notwithstanding, wild tales about that birthday gala, what happened both before and after the event, are various and sundry; virtually all of them are apocryphal. One author, for example, described a Marilyn Monroe who was so drunk and drug-addled that she could not locate the stage, leading to her offensive tardiness and presidential disrespect, most certainly false and ridiculous, considering the number of persons who would have observed Marilyn drunkenly wandering about; and while Mark Shaw did not claim Marilyn was overcome by drugs and alcohol, wandering lost during that presidential event, the author still joined the ripping yarn-spinning fun.

Shaw began by declaring that the identity of the person whose idea it was to extend an invitation for Marilyn to appear at the president’s birthday celebration had yet to be discovered (Shaw 391). Odd. Gary Vitacco-Robles reported: It was Peter Lawford’s idea for Marilyn to sing “Happy Birthday” to the president in her sexy, whispery voice in the event’s climax (Vitacco-Robles KEv2:25). Hoover’s federal bureau agreed, and asserted in a few 1962 vintage FBI memoranda, that Lawford was the inviter. Even so, I have read accounts which asserted that the invitation actually arrived via President Kennedy himself during his desert rendezvous with Marilyn in late March of 1962; and I have also read accounts that Richard Adler, the musical director of the birthday gala, actually proposed Marilyn’s appearance to John Kennedy, a proposal that the president readily accepted. Still, does it really matter who actually extended the invitation? Obviously, her appearance had been approved by the White House as proven by Kenneth O’Donnell’s April 11th letter thanking Marilyn for agreeing to appear. Shaw even included the text of O’Donnell’s letter in his book. Apparently Shaw simply wanted to imply that Marilyn’s appearance at the May event was an odd mistake or happened accidentally; or perhaps, Shaw simply wanted to lay a foundation for his next assertion: President Kennedy probably never knew that the song was almost stricken from the program since her rehearsal was so “steamy” that […] Richard Adler wanted to drop it as being too risqué (Shaw 392).

By all accounts, Marilyn constantly rehearsed how she would deliver the song even before she flew to Manhattan with Pat Newcomb and Peter Lawford. On Friday, May the 18th, Richard Adler rehearsed with Marilyn in her apartment for three hours. Due to Marilyn’s sensual delivery of the birthday song, Adler reminded Marilyn of her previous promise to wear a sedate, high-necked black gown befitting a presidential event, a promise, of course, she did not and never intended to keep. During a rehearsal held at Madison Square Garden, Marilyn performed the song as she intended to deliver it and she enacted all her carefully choreographed motions and movements. According to Susan Strasberg, Adler remained concerned and forced Peter Lawford to telephone President Kennedy with a warning; but the president just laughed and said, “Great” (Strasberg 245).1Strasberg, Susan. Marilyn and Me: Sisters, Rivals, Friends. New York: Warner Books, 1992.Therefore, according to Susan, who attended and witnessed the event, President Kennedy knew how Marilyn would perform and was not the least bit concerned. On his website, The Marilyn Monroe Collection, Scott Fortner appropriately asserted: Marilyn Monroe had every intention of signing the song exactly the way she sang it: Sexy, breathy, sultry. She planned it, she rehearsed it, and she sang it the way she intended to, and President Kennedy knew it was coming. Obviously, Mark Shaw should have consulted a few of his reliable sources, like Gianni Russo.

Virtually, every newspaper, glossy magazine and e-zine article written about that gown has declared, and journalists continue to declare, that Marilyn was literally sewn into the dress; and, of course, she could not wear any lady’s foundational garments. Thus, she went commando! One such article exclaimed that the dress did not even have a zipper!

Engaging in an apparent bout of one-upsmanship, Mark Shaw declared: The dress, with all its inserted beads (it took five hundred backstage stitches to assemble the dress onto Marilyn’s famous form), was said to have cost $12,000 in 1962 (Shaw 394).2Actually, a minor detail, Marilyn paid slightly less than $1.5K for the dress in 1962. At auction in 1999, when the dress sold for slightly over $1.25M, the original cost, when adjusted for inflation, would have been slightly more than $8K. The cost of the dress in 2020 currency would have been slightly more than $12K.The preceding multi-stitch declaration certainly represents the height of hyperbole regarding the famous dress and also suggests several interesting inevitabilities: 1) Marilyn went to the Garden that night wearing something that Shaw did not identify, nor did anybody else for that matter; 2) for Marilyn to have exited the dress later that night, at least a large portion of the five-hundred stitches must have been unstitched by a person or persons that Shaw did not identify, nor did anybody else for that matter; 3) at some point, Marilyn must have paid an unknown person, or unknown persons, to reassemble the dress onto a form that perfectly matched hers; 4) Martin Zweig, who purchased the dress in 1999, must have paid an unknown person, or unknown persons, to disassemble and then reassemble the dress onto a clear Marilyn-matching form before he placed the dress in a climate controlled vitrine; and 5) most certainly, the assembly and disassembly would have damaged what has been described as an extremely sheer and delicate fabric. However, the dress displays no damage. Of course, none of the preceding has ever been mentioned by any author, much less even considered, because proffering wild allegations is all that matters.

Marilyn commissioned a co-conspirator, Jean-Louis, to design a full-length gown that “only Marilyn Monroe could wear” (Vitacco-Robles KEv2:25), one that would really rankle and rattle Richard Adler and shock the event’s audience. Evidently the dress’s designer and his crew of pattern cutters worked secretly for days, in Marilyn’s Fifth Helena dressing room, to shape and fit the pattern against Marilyn’s naked body, ensuring that the body stocking would fit precisely; but was the dress actually sewn, assembled onto Marilyn’s body?

First, the zipper. The dress contained a clear plastic zipper, reported biographer Gary Vitacco-Robles, and tiny hooks sewn by hand to ensure that it fit like a second skin (Vitacco-Robles KEv2:25). Below are photographs which conclusively prove that the dress had a rear zipper; and photographs of Marilyn, taken from behind her as she sang, clearly revealed the zipper, confirmed by the far right hand black and white photograph in the panel below.

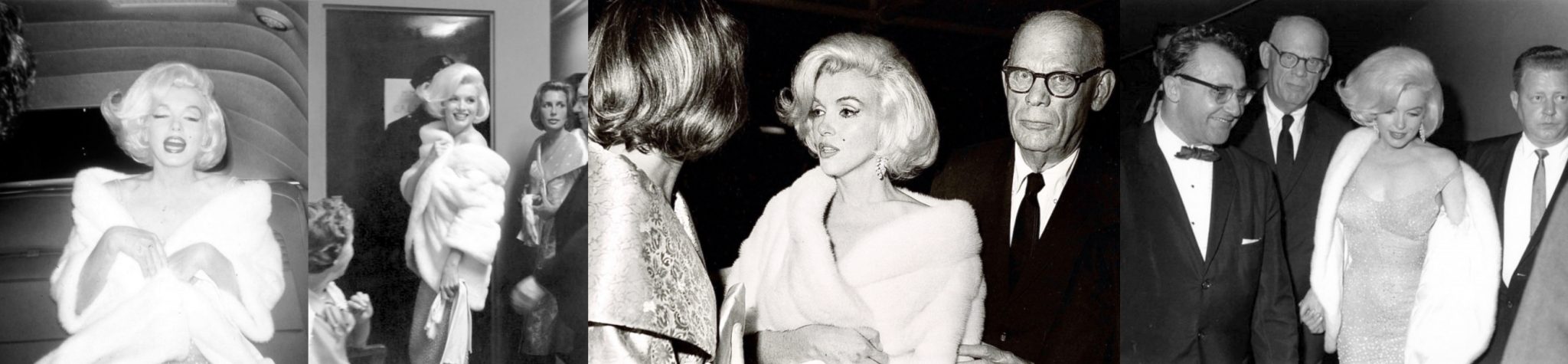

Second, the assembly backstage. On that evening in May of 1962, Marilyn and Pat Newcomb left the former’s Manhattan apartment together and boarded a limousine, which then proceeded to Brooklyn and collected Isadore Miller. The limousine then delivered the trio to the Four Seasons restaurant for dinner and finally to Madison Square Garden (Vitacco-Robles KEv2:25). Beginning from the left, the first photograph in the panel displayed below is Marilyn seated in the limousine, preparing to depart for Brooklyn; the second photograph depicts the arrival of Marilyn and Pat Newcomb; the third and fourth photograph include Isadore Miller. Obviously, Marilyn left her apartment wearing the gown with the hair already properly styled. The gown was not assembled onto Marilyn backstage by seamstresses wielding pins and needles and flesh colored thread with thimble adorned but nonetheless nimble fingers.

Not satisfied to rest on the laurels of his preceding pronouncements, Shaw saved his best for last. He noted that Peter Lawford, aware of her propensity for being tardy, introduced Marilyn repeatedly as the long evening progressed, only to look back at an empty stage, followed by Lawford’s introduction of the next speaker. Shaw then asserted: Lawford became frustrated but as the night of celebration wore on, Marilyn finally shimmed onto the stage (Shaw 394). Of course, Lawford did not know that Marilyn would soon depart Mother Earth; so when Marilyn finally appeared in the spotlight, Lawford welcomed her to the stage as “the late Marilyn Monroe” (Shaw 394).

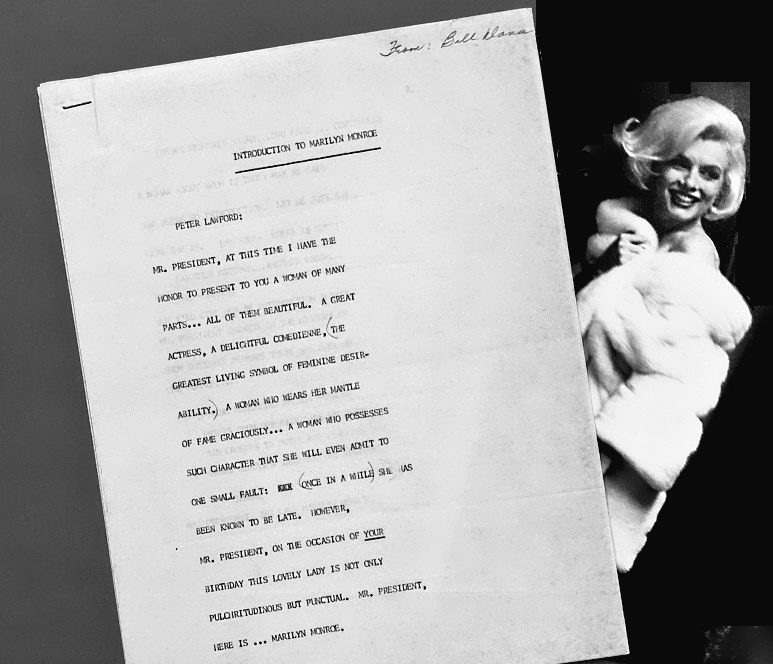

Of course, the gag pertaining to Marilyn’s tardiness was always a part of the big show, both to add some humor and to build some suspense, some doubt regarding Marilyn’s appearance—was she actually going to appear?—and regarding Peter Lawford’s elaborate introductions, the photograph displayed below depicts the first page of the script the actor used to introduce Marilyn; and introducing the actress as the late Marilyn Monroe was also part of the script, a comic punch line suggested by the comedian William Szathmary, otherwise known as Bill Dana, whose name is clearly visible on Lawford’s script.

Finally, Marilyn’s scintillating performance was intricately planned and frequently rehearsed, including her sexual mannerism, including her suddenly altered body language as she reached the words Mr. President, prompting her to assume an erect posture of feigned and demure dignity with presidential deference. Nothing about Lawford’s introductions or Marilyn’s performance was impromptu or left to chance; and nothing about her performance shocked or disturbed the Kennedys, especially President Kennedy: he, in fact, received exactly what he evidently wanted, as his humorous comments at the close of the evening clearly indicated: I can now retire from politics after having Happy Birthday sung to me in such a sweet and wholesome way. Suggestions by Mark Shaw, and other like-minded authors, that Marilyn’s historic gown and her historic performance on May the 19th in 1962 were related to her death, her murder because she embarrassed the rotten Kennedys is pure bunkum and, yet again, a disingenuous attempt to create evidence of nefarious intent (Shaw 101). How sadly disappointing would it have been for Marilyn Monroe, the world’s sex goddess, to appear and deliver “Happy Birthday” to a vibrant President John Kennedy just like she would have delivered it to Gianni Russo on his sixth birthday. That, of course, would have been incredibly silly, not to even mention incredibly dull.

One closing puzzlement. If seamstresses stitched Marilyn’s twinkly gown around her curves so snugly that she could barely take steps, as alleged by Mark Shaw and others of his ilk, and if we briefly accept that she and President Kennedy performed the horizontal bop following the birthday gala’s events, then what happened when she and he got to the Carlyle Hotel? Marilyn most certainly must have disrobed; but how did Marilyn extricate herself from her gown’s smooth and silky embrace? Who de-stitched the stitches? Did the president perform the de-stitching chore? Also, a shoeless Marilyn was dressed in the gown when she met and spoke briefly to James Haspiel curbside at her apartment. After the sexual episode at the Carlyle, who re-stitched the gown around Marilyn’s body? The president? Perhaps his Secret Service contingent also carried, along with their pistols, pins and needles, thimbles and thread just in case they had to remove and reapply an extremely snug-fitting and sparkly evening gown from one of the president’s doxies. While the preceding may sound ridiculously contrived, it is no more ridiculous or contrived than the many unfounded and unsubstantiated yarns told about Marilyn Monroe and John Kennedy that have been thoughtlessly repeated for sixty-one years.