Widespread Editing and Developing Anecdotes

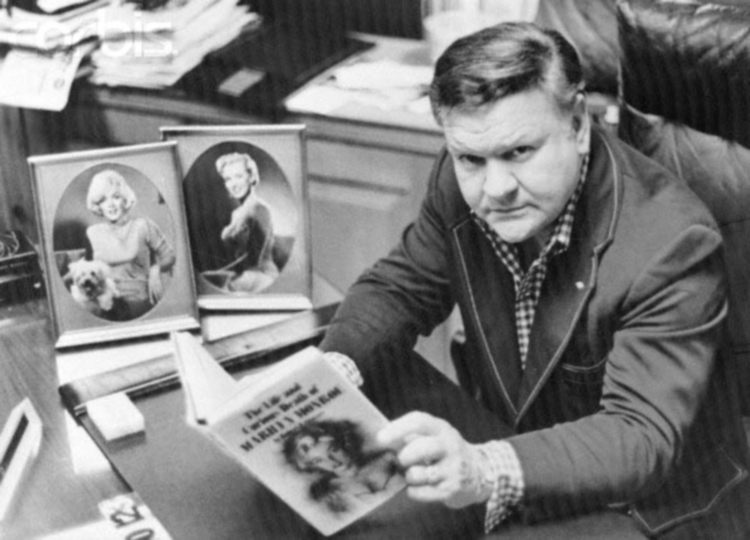

As a neophyte who once wandered virtually unguided through the labyrinth of book creation and construction, I do not know, at least not conclusively, how many editors normally suggest, structure and trim, editorially build a manuscript. Regarding The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe, many workmen, both known and unknown, members of what was essentially a literary general contractor, a writing conglomerate, assembled and constructed Slatzer’s Marilyn Monroe artifice; and the Fowler Papers provided the evidence and proof of that construction.

As I announced in my Author’s Note regarding this website version of Murder Orthodoxies, from the Oviatt Library and “The William Randolph Fowler Collection,” I obtained over nine-hundred pages of Fowler’s collected documents; and of that quantity, 260 pages carried copies of articles from either newspapers or magazines, but primarily magazines. The publication dates ranged from 1962 to 1994; however, the majority of the articles appeared in various magazines published during 1972, just prior to the tenth anniversary of Marilyn’s death, along with magazines published in 1973 which trumpeted Norman Mailer’s now known to be factoidal and fraudulent novel biographical novel. 1972, of course, was the year Slatzer and Fowler began to construct the artifice which became The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe.

Regarding the many pages of editorializing contained in the Fowler Papers, some had been typewritten while some had been written in longhand, clarifying, due to penmanship differences, that several editors, or more precisely identified as commenters, offered instructions and opinions pertaining to the manuscript’s contents and other issues. You might be thinking, asking yourself: why would a book, essentially a recitation of actual events, require a substantial amount of editing? A fair question, I submit; but if the book was an artifice, an amalgam of disparate and incongruous parts, both stylistically and tonally, then a considerable amount of touch-up would certainly be required to create a narrative that spoke with one consistent voice; but in that regard, in my opinion anyway, the touch-up was only marginally successful.

An unidentified editor hand wrote instructions on several articles which appeared in a magazine devoted entirely to Marilyn’s last untold secrets.1According to various retail websites offering copies of that single edition glossy for sale, it appeared on newsstands not long after Marilyn’s death.Using handwritten notes Slatzer sent to Fowler as a comparative basis and an indicator, I am reasonably certain that unidentified editor was Robert Slatzer.

To an article entitled “The Making of a Star” written by Carol David, Slatzer noted: Add chapter on this and beauty; and then to an article entitled “Marilyn’s Last Predictions”, he noted: play him down―out of future plans, etc; the him to whom Slatzer referred was Joe DiMaggio; and to an article entitled “The Last Lonely Days” written by Martin Buckley, Slatzer noted: at Brentwood chapter. Slatzer obviously wanted Fowler, or whoever was actively writing at that time, to borrow from Buckley’s article as necessary to generate or supplement a chapter pertaining to Marilyn’s Brentwood residency on Fifth Helena Drive; and on several other magazine pieces about Marilyn, an editor underlined or otherwise highlighted various passages therein, obviously marking what could or should be employed in Slatzer’s developing book. The October 16th issue of Newsweek, for instance, published in 1972, contained two such articles, one written by Norman Rosten, Marilyn’s poet friend, and a lengthy one written by Joshua Logan, who directed the movie, Bus Stop.

The writers, the editors and the commenters developing Slatzer’s publication found Norman Mailer’s faux biography more than interesting. After the factoidal biography’s publication in 1973, many articles appeared in more than a few media publications, articles pertaining to Mailer’s characterization of his sweet angel of sex, the silver witch of us all, pertaining to his evaluation and opinion of her, along with his murder insinuations involving the middle Kennedy brothers. The National Insider, May 13th edition, and Midnight, June 4th edition, were two such publications, whereas the Ladies Home Journal published excerpts from Mailer’s artifice in both July and August of 1973. An editor, possibly Slatzer or an unknown writer, someone, underlined many passages in those articles and also underlined portions of the excerpts from Mailer’s book.

Editors came to my house a few times while I was writing […] ate meals and stayed ’til early morning hours, Fowler revealed in his notes. One was named Andy […], most certainly Pinnacle’s Andy Ettinger, who possibly edited the text along with Will Fowler.2WRFC Box 21, Folder 4, page 13.After all, Fowler’s declared opinion of Slatzer’s abilities as a writer did not contain a recommendation approaching a compliment; and John Gilmore also shared Fowler’s low opinion of Slatzer’s writing skills. Certainly, then, Fowler edited textual portions Slatzer might have later contributed.

Frank Capell certainly availed himself of the opportunity to include his building materials in Slatzer’s artifice. In Slatzer’s 1973 March letter to Capell, referenced earlier, Slatzer noted that Will Fowler had already started working with Capell’s collection of Kennedy files. Will [Fowler] should be able to commence carrying on alone with the finished writing, Slatzer notified Capell and then added: After that, he [Fowler] will start sending you chapter-by-chapter in order that you may tell us what to add and what to remove because of libel.3WRFC

Box 23,

Folder 27,

page 3.Slatzer’s expressed concern regarding libel is curious, to say the least, considering that written declarations are termed libelous only when and if those declarations are intentionally malicious and obviously false. Slatzer’s memoir, we have been led to believe, presented and contained the truth and nothing but the truth.

Another unidentified editor provided commentary and instructions, entitled Initial Broad Editing of First Marilyn Monroe Papers 91 pg. MS. I initially believed that the capital letters MS represented the initials of the editor; but I am now relatively confident that those initials are an odd acronym for the word ManuScript; but be that as it may, the unidentified editor’s document instructed the writer, in part, as follows:

Eliminate pg.16, which leads into eventual astrology bit. I believe to keep this book out of the trash range, we’ll have to eliminate many things, such as astrology and astrology charts. […]

Also, National Enquirer should not be mentioned in that critics will associate this with the possible class of the book.

Eliminate first 9 lines on pg. 17.

Lead in your first meeting MM with pg 17 Barrymore meeting in Ohio, then rewrite through pg. 28, and include high school correspondence you have, along with high school picture. Get MM tape quotes re her childhood. Also in this section, add first meeting sex scene I wrote. Expand on James Dougherty’s b.g. here.

In more than a few locations, that particular editor presented the writer with an interesting but nebulous directive, to leave room for imagination. Was that editor directing Will Fowler to liberally employ his imagination? Or was he directing Will Fowler to merely write with a suggestive economy, thereby leaving space for the magical wizardry of a reader’s imagination to project and contrive?

At least two other unidentified editors suggested, and in several instances, actually ordered revisions to the manuscript as the contrivance progressed. Perhaps one of those editors was Andy Ettinger, or one of the two others dispatched by Pinnacle to visit Will Fowler, or Frank Capell or possibly Donald Shepherd, a literary agent employed by both Robert Slatzer and Will Fowler, or Al Stump, another possible editor Fowler mentioned and the man who, Fowler asserted, recommended changing the name of Slatzer’s book from “The Marilyn Monroe Papers” to The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe.

As an aside, Al Stump co-authored Ty Cobb’s posthumously published autobiography, My Life in Baseball: The True Record. Following Cobb’s 1961 death, Stump wrote an unfavorable account of Cobb’s last few months alive; and he also wrote two additional pathographies about Cobb, one of which became the basis for Hollywood’s 1994 biopic about the baseball great, entitled Cobb. Stump’s writings created the image of Cobb the sociopath, a singularly deplorable racist and baseball player who sharpened his spikes into weapons that he then used to intentionally injure fellow players. Many baseball historians now consider most of Stump’s writings about the Georgia Peach to be fabricated, an elaborate myth created by the biographer simply for financial gain. I must confess: I do not know for true if Al Stump edited The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe. I could not find any evidence that he worked for Pinnacle Books; but considering the involvement of Frank Capell, considering also the sportswriter’s historically questionable accounts about Cobb and Cobb’s life, Stump would have been a perfect fit. And too, it appears as if Cobb and Marilyn shared a similar biographical misfortune, mistreatment and misrepresentation.

Earlier in Section 4, I mentioned that Donald Shepherd and Robert Slatzer co-authored a Bing Crosby biography, published in 1981 and then a John Wayne biography, published in 1984. Also, according to Fowler’s Papers, Shepherd negotiated with Pinnacle on Fowler’s behalf; but, unfortunately, Fowler’s note regarding Shepherd’s negotiations did not clarify their purpose; but most unfortunately, the identities of all the editors and commenters involved with creating Slatzer’s manuscript will forever remain a mystery. Most certainly the identity of the editor who wrote the sex scene attached to Slatzer’s alleged first meeting with Norma Jeane will never be known, an alleged first meeting memorialized in chapter seven of Slatzer’s book.4The Fowler Papers contained the copy of a check, dated June 15, 1973, in the amount of $15K. The check was made payable to the Don Shepherd Agency: As per contract June 9, 1973 for the Marilyn Monroe Book by Robert F. Slatzer.

A rather significant event in the life of Robert F. Slatzer, a fellow might anticipate, expect that he could recount, with some certitude, what happened during that meeting if it had actually transpired; but the first meeting anecdote, along with others, appeared in the Fowler Papers at various stages of editorial development, complete with curious differences between the developing versions and how the anecdote appeared in the finished and published concoction. For instance, the description of the Norma Jeane who entered Fox studio’s lobby on that eventful day was not consistently presented: in the developing versions, she underwent several changes. The editors could not decide on the color of Norma’s hair, for instance, or her actual surname; they could not decide on Norma’s actual demeanor or the effect of her voice; and they misspelled her complicated middle name; but in the book’s published version, Norma became a Dougherty; and the editors finally awarded her curly brown hair, a shy demeanor, a breathy, put-on, sensual voice (Slatzer 84) and a middle name spelled Jeane; but more importantly, the after dinner, late night skinny dip in the Pacific Ocean did not appear in any of the anecdote’s developing versions, only the final published concoction, most certainly as prescribed by the editor who actually composed the obligatory sex scene.

Although there are several details presented in Slatzer’s first meeting anecdote that are demonstrably false, one detail in particular about the beautiful girl Slatzer allegedly encountered that day disproves his first meeting account; and, too, what were the actual circumstances surrounding and the events shaping Norma Jeane’s life during the time Slatzer claimed that he fortuitously encountered her?

The exact date of that fateful first meeting was not noted in Slatzer’s 1974 published account, a tactic of vagueness he regularly employed. Slatzer only asserted that he met Norma Jeane quite by accident in the lobby of Fox Studios during June of 1946, the meeting that began their relationship and their love affair; but according to a note contained in the Fowler Papers, Slatzer informed his writing partner that the first encounter with Norma Jeane specifically occurred on July the 11th, a Thursday.5WRFC

Box 21, Folder 4, pages 24 and 51, both handwritten notes.Winding the clock backward a few months to the fall of 1945, after Norma Jeane became involved with the Blue Book Modeling Agency, the agency’s owner and director, Emmeline Snively, encouraged her new model to lighten the color of her hair for professional reasons. Initially Norma resisted doing so; but she eventually acceded to Emmeline’s suggestion and began a lightening and a straightening process during February of 1946; both processes required a few salon visits to complete. Even so, by June of 1946, the texture of Norma Jeane’s hair and its color had been transformed from a curly and unruly reddish brown into a much more relaxed and straighter honey blonde. Had Slatzer encountered Norma Jeane in June or July of 1946, as he asserted, he would have encountered a blonde-haired Norma.

Sometime during January of 1946, Norma Jeane finally accepted that her mother-in-law, Ethel Dougherty, and her husband, Jimmie, would never accept her new modeling career; and due to Ethel’s constant disparaging, disapproving comments and complaints, Norma left the Dougherty’s household, where she was living at the time, and returned to Ana Lower’s Nebraska Avenue house. By late spring, the marital issue of her modeling career unresolved, Norma decided she had but one choice: divorce. Her next and obvious choice for gaining a divorce quickly was the state of Nevada, which required only a brief period of residency prior to filing a divorce petition. So on May the 14th, Norma traveled to Las Vegas and moved in with Grace Goddard’s sixty-nine-year-old widowed aunt, Minnie Willette. Therefore, Norma was not living in Los Angeles during the months of June or July and part of August in 1946.

According to several biographers, Norma Jeane returned to Los Angeles on two occasions and risked being caught in violation of Nevada’s residency statute. During her first clandestine trip to Los Angeles, she moved out of Ana Lower’s house and into the Studio Club, located at 1215 North Lodi Place. She then returned to Las Vegas and continued her statutory residency; but her second clandestine trip to Los Angeles was for a much more significant reason.

Donald Spoto reported that Norma Jeane slipped quietly back to Los Angeles because Helen “Cupid” Ainsworth, Emmeline Snively’s friend and a managing agent with National Concert Artists Corporation, had arranged a meeting for Norma with 20th Century-Fox Film Corporation (Spoto 109). There are varying opinions on the date of Norma Jeane’s significant meeting with Ben Lyon, Fox’s talent and casting director. Some biographers have asserted a meeting date of July the 17th while others have asserted a meeting date of July the 25th. Even so and regardless of the actual date, several biographers have reported that either Cupid Ainsworth or Harry Lipton accompanied Norma to her meeting with Ben Lyon; but the point is this: Norma did not have any reason to visit or any scheduled meeting at Fox Studios in June of 1946; and her meeting with Ben Lyon did not transpire on July the 11th, either.

Years later, Lyon vividly recalled his initial encounter with Norma Jeane in his Fox Studios’ office, the painted walls of which matched the dark green color of jungle foliage. He recalled how the vision of Norma Jeane standing in his office took his breath away. That dark green wall, the striving colors of that office of mine, he wistfully recalled, made the perfect setting for her golden hair, peaches-and-cream complexion and the simple little flowered cotton dress she was wearing―an inexpensive dress but nicely cut and very nicely filled out (Eubank 88). Once again, the beautiful young woman who entered Lyon’s office that summer day did not have curly brown hair.

On August the 30th in 1972, Slatzer dispatched a typewritten communication to Fowler. It recounted an evening date Slatzer shared with his new lover and companion, a story that Fowler could possibly use in their fictional book project, the one to be entitled “The Beautiful Loser.” Since Fowler never wrote that fictional book, the evening date anecdote appeared in chapter fifteen of Slatzer’s memoir, a recounting of an adventure to which Norma Jeane had attached a name: She always called it the “watermelon disaster” (Slatzer 193).

Slatzer informed Fowler at the start of the August 30th communication: The following is an incident involving myself and Marilyn in the late forties; however, the 1972 version written by Slatzer differed considerably from the version which appeared in the conglomerate’s 1974 published apocrypha. For instance, the occasion for the date as presented in the 1972 version was attending a movie, something that was playing at the Pantages Theatre, Any Number Can Play;6Released in 1949, Any Number Can Play, a drama which featured the vice of gambling, starred Clark Gable, Alexis Smith, Mary Astor, William Conrad and Edgar Buchanan. Directed by Mervyn LeRoy, the film was produced and released by MGM. It opened in New York City on the 30th of June in 1949 and elsewhere in the US on the 15th of July.but, in the 1974 published version, the occasion was visiting a Madame Something-Or-Other gypsy fortune teller. The gypsy sibylline seer did not appear in Slatzer’s 1972 version of the evening date.

Other details included in the 1972 version did not appear in the 1974 publication, either, twelve pages of details: an aging colored wino with a switchblade; a search for the perfect watermelon which the adventurers found in a produce market; a trip to Slatzer’s hotel where he dropped the perfect melon in the lobby, resulting in its destruction and melon splatter landing on his and his date’s shoes and legs; an elevator ride up to his hot hotel room where they used the bathroom’s total supply of clean towels to remove the melon fragments from them-selves, after which, from a bottle of Scotch, they each had a drink before Marilyn washed the legs of Slatzer’s trousers. Marilyn then removed her pulp-stained shoes and reddened hose. Not long thereafter, according to Slatzer’s 1972 version, a bellhop delivered an iron to the room, so Marilyn dutifully ironed her date’s once melon-stained britches; and she did a good job, too, Slatzer observed with a certain incredulity. Marilyn then slumped into the only comfortable chair in the room, an overstuffed chair that looked like it came from a Mississippi whore house. Eventually, with the lights off, Slatzer stretched out on the bed. Finally, Marilyn stretched out alongside Slatzer; and his thoughts veered into his physical pains and his feelings about the evening.

My back felt strained. My shoulders were aching. And the whole pilgrimage to the market had been folly; I felt a little sorry for the girl beside me. In many ways, she was still like a child that had not grown up. But I also felt kind of special. Who else could say that Marilyn Monroe once pressed their pants?7WFRC Box 19, Folder 12.

None of the preceding from the 1972 watermelon anecdote as recounted by Slatzer, along with many other contradictory details, found their way into the 1974 publication; but then, an editor, possibly Fowler, possibly Capell, or possibly even Andy Ettinger, condensed the twelve typewritten and double-spaced pages Slatzer submitted to Fowler in 1972 into slightly over two pages of text which appeared in the 1974 publication. Even though I could mention many additional differences between the 1972 and the 1974 versions of the watermelon disaster, to do so would merely belabor the point.

All of the preceding can only be interpreted one way: the newspaper and magazine articles along with the information extracted from Mailer’s faux biography became source material for the editors, commenters and writers creating Slatzer’s book. It all rings with such phoniness that it emits the muted tones of a plastic bell. Certainly a man who participated in an intimate, conversation-filled, sixteen year relationship with Marilyn Monroe, during which she told him her life story, a large portion of which he actually shared, that man would not need source material about the woman he loved or the life they shared; and why would the events defining that life and that relationship need to be editorially developed? Certainly, also, if Slatzer and Marilyn actually shared the type of relationship he alleged and, likewise, he was actually the type of confidant he alleged, then he would simply have known the facts, simply have known the details, simply have known. Additionally, all of the editorial modifications, all the dialogue variations and the developing anecdotes advance more than a reasonable doubt regarding Slatzer’s verity and the verity of his story; but still, I admit that I have, in effect, belabored the point, which is this: The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe was not a recounting of actual events that actually occurred; it was a fantasized account of imaginary events involving a relationship that never existed.