The Slatzer’s Nuptial Celebration with Carlos Arruza

If the Rosarito Beach Hotel housed a fine restaurant in 1952, and apparently it did, why did the honeymooning Slatzers need to travel into Tijuana to dine at the Foreign Club? I suggest that most normally motivated newlyweds would have chosen to remain within the proximity of their bed; but then, perhaps I am merely projecting: that proximity is what I would have chosen. And too, perhaps, after several years in a relationship that Slatzer suggested was a connubial clone, their sexual dance, once a passionate paso doble had, by familiarity and frequency of occurrence, devolved into a boring basic waltz. At any rate, there are problems with Robert Slatzer’s Tijuana Foreign Club story and his putative friend, the well-known and unusually famous bullfighter, Carlos Arruza.

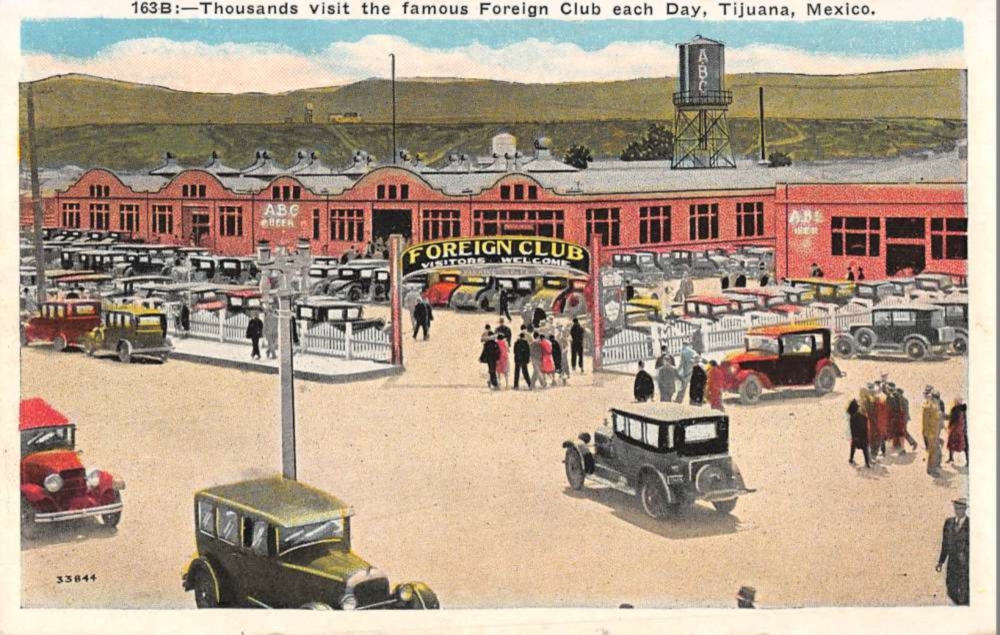

It appears that the Foreign Club was a very swanky, popular club and casino in Tijuana; but, according to my research, the club only operated from 1920 through 1935. During Prohibition, many similar clubs appeared just south of the border from San Diego; but once the American government repealed its ban on alcohol consumption in December of 1933, and California also legalized parimutuel betting, many of those American-owned Mexican clubs became financially insolvent and closed. In 1935, the Foreign Club could have been purchased by Mexican investors, of course; but, I did not find any indications that such a business transaction occurred. Moreover, I did not locate any contemporaneous photographs of a Foreign Club which exists in Tijuana today or one that existed there in 1952.

The depictions of the club that have survived are actually architectural renderings included on old postcards depicting men and women wearing clothes and riding in automobiles associated with the Roaring Twenties. Additionally, the buildings depicted on those postcards are not always the same. On one postcard, for example, the rendering depicted what is called The Foreign Club Café, Honold’s Duty Free Importations, and the buildings resembled other postcards which depicted what is merely called The Foreign Club. A few of the postcards I uncovered appeared to depict a race track behind the club, possibly for racing horses or dogs or both. While additional investigation pertaining to the existence of a 1952 version of the Foreign Club proved to be inconclusive, additional probing produced additional problems with Slatzer’s Carlos Arruza anecdote.

Owned and staffed by white Americans, Mexicans and blacks were not allowed to enter The Foreign Club. It was a place where wealthy segregationist Americans could drink alcohol legally during prohibition and could legally gamble in a casino environment. If the club was segregated, which appears to have been the case, then an obvious question comes to mind. Slatzer identified Carlos Arruza, a Mexican torero, as a friend who celebrated their marriage when the newlyweds returned to the Foreign Club. Would that celebration have been possible assuming a segregated Foreign Club was open in 1952?

If segregationist rules incited by prejudice kept Mexicans from entering The Foreign Club, those rules probably would have been relaxed for Carlos Arruza, nicknamed El Ciclón, or The Cyclone, by his host of adoring fans. If he was not the most respected and famous matador of the twentieth century, Arruza was certainly the most wealthy. At the height of his career during the forties, he commanded the highest fee per bullfight. Thus, he became a multi-millionaire, owned enormous ranches in both Mexico and Spain. On those ranches, he raised both domestic cattle and fighting bulls.

In 1955, Barnaby Conrad translated and transcribed Arruza’s autobiography from the matador’s handwritten Spanish manuscript. Published in 1956, My Life As A Matador: The Autobiography of Carlos Arruza, Conrad wrote in his foreword: Until his retirement to the Good Life in 1953, Carlos Arruza was the highest paid athlete in the world and possibly the greatest single drawing attraction in the history of bullfighting (Conrad 1). Although Arruza performed occasionally in Mexico City and a few times in Tijuana, he most often toured the bullfighting rings in Spain, Portugal and France, nations in which only a handful of bullfighting Spaniards rivaled Arruza’s fame. He was perhaps the most original and innovative bullfighter of his time, with several unique moves accredited to him. In 1972, six years after Arruza’s death, the city of Tucson, dedicated a street to the torero: Calle Carlos Arruza. He is possibly the only bullfighter in the history of the sport to be honored by the attachment of his name to an American street, a dedication that occurred when an eponymous biographical film about the matador premièred in Tucson; and that event leads me directly to Arruza’s film career and Hollywood.

During their initial encounter with Carlos at the Foreign Club, he joined Slatzer and Marilyn for dinner before the wedding ceremony. According to Slatzer, an intoxicated Marilyn commented to Carlos: Would I insult you if I told you that you remind me of Rudolph Valentino? Arruza putatively answered: I would be most honored. But I must admit I am not an actor. I face reality. I have no lines, only actions, and I play to an emotional and over demanding crowd (Slatzer 156). Slatzer did not mention anything, neither to Marilyn nor within his narrative, about Arruza’s involvement with cinema.

Arruza was not a stranger to Hollywood, to Mexican or American movies. In 1944, he appeared in the comic drama, Mi Reino por un toreroin. Arruza also appeared in several documentaries about bull fighting: in 1948, Toros y toreros; in 1951, Bullfight; in 1956, Torero. He was the technical advisor for The Magnificent Matador, a film starring Anthony Quinn and Maureen O’Hara released in 1955. Quinn narrated the biographical documentary about Arruza. The matador portrayed Lt. Reyes in John Wayne’s The Alamo in 1960. He appeared on The Dinah Shore Chevy Show, also in 1960; and in 1963, he appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. In 1965, archival footage of Arruza appeared in Historias de la fiesta. In his autobiography, Arruza recounted his romantic relationship with a dark-haired and beautiful Hollywood actress. He did not identify her; and he did not provide any indication of when the Hollywood romance occurred. Arruza’s autobiography suffered from a glaring but common defect: the absence of calendar dates for most of the events therein described. One of the few dates he provided involved his final bullfight, one staged for charity. In Mexico City, on February the 23rd, in 1953, Barnaby Conrad delivered Gary Cooper and the Mexican actress Loraine Chanel to Arruza’s dressing room to observe Arruza’s dressing ritual. Arruza announced to both Cooper and Miss Chanel that he was dressing in the suit of lights for the final time.

Here’s the question and the navel of this orange. In his autobiography, did Carlos Arruza mention an encounter with Marilyn Monroe in Tijuana? Did he mention that he attended a shoeless Marilyn’s wedding reception at Tijuana’s swank Foreign Club in October of 1952? Did he mention his lucky American friend, Robert Slatzer? The answer is, as you have probably already anticipated, nada. Considering that Marilyn was already a famous actress by then, had appeared in eighteen movies and countless film clips, had appeared clothed on many magazine covers and nude on a calendar, which had appeared in June of 1952, and considering Carlos Arruza’s familiarity with Hollywood, Marilyn’s absence from his autobiography is certainly significant. Additionally, as an aside, I assume, since Marilyn remained shoeless after her wedding ceremony, dining barefoot in a fine restaurant was acceptable in 1952 Tijuana.

Admittedly, I do not know for true if Carlos Arruza and Robert Slatzer were friends or if they ever met; but in my opinion, the probability that Arruza encountered the alleged newlyweds in October of 1952 is no higher than absolute zero; but certainly only you can decide if you believe Slatzer’s anecdote. However, before you decide, allow me to offer a final observation about this Slatzer alleged incident.

Marilyn was a true animal lover, a lover of all animals, even bovines. During her marriage to James Dougherty, as he recounted on several occasions, Norma Jeane tried to pull a mooing cow indoors and out of the rain: she feared the cow was in distress. When Arruza retired in 1953, by his own admission, he had killed 1,260 horned animals during bullfighting contests around the world. I find it difficult to believe that Marilyn would have been so enamored of Arruza’s profession that she would have asked for a guided tour of his bull-scarred body; but then, according to his autobiography, bulls gored Arruza only seven times during a career that began when he was the age of thirteen. Even so, he carried a prominent scar, one not inflicted by a bull in the ring.

Conrad noted that Arruza’s most prominent scar began on the back of his neck from where it jagged up to his left ear, a total of eight inches in length, inflicted by a taxi driver who, after an automobile accident involving Arruza and his car, became unhinged and slashed Arruza with a knife. According to Conrad, the bullfighter invariably told American tourists, because the story sounded more romantic, that an enormous Miura bull had inflicted the wound that left the nasty scar. Revealing, is it not, that Slatzer never mentioned and Marilyn never noticed, nor asked about, that prominent and jagged scar. She never heard Carlos’ romantic tale involving that imaginary Miura bull.

Even though Arruza wrote his autobiographical manuscript in Spanish, he spoke English, but with a musical Latin accent. Conrad noted that Arruza was often troubled by his less than stellar English pronunciations; but his problems with the language also produced his charming boyish smile, which, when combined with his musical manner of speaking, resulted in a captivating countenance. Robert Slatzer did not mention his alleged friend’s captivating qualities, however, nor his alleged friend’s musical Latin accent; and as far as I know, Marilyn never mentioned that she knew or had ever met the famous Mexican matador El Ciclón, Carlos Arruza.