The President's Best Buddy

We all have a best buddy or a best girlfriend, at least I assume so, that boy or girl, man or woman on whom we can rely for some advice or some comfort, a good chess match or a good game of checkers, one special person in our lives who is always willing and ready to help. Allegedly, New Jersey born, George Armistead Smathers was John Kennedy’s best buddy; and how do we know that George was John’s best buddy? George told us that he was; and it must be acknowledged that Smathers was one of only a few non-Kennedy and non-Bouvier human beings to attend John Kennedy’s wedding to Jacqueline Bouvier. At the 1953 marital ceremony, Smathers was an usher for the groom, despite advising Mr. Kennedy not to marry Miss Bouvier and despite his opinion that the soon to be Mrs. John F. Kennedy was not sophisticated enough for the Massachusetts Senator. Smathers apparently believed that the twenty-four year old brunette beauty was not urbane, not quite self-confident enough to disregard John Kennedy’s skirt chasing, an activity in which he would engage, Smathers knew, with or without a gold band around the finger that connects directly to a man’s heart.

Both John Kennedy and George Smathers shared an insatiable desire for beautiful and sexy women; and the conquest of women was the main basis, arguably perhaps the only basis, for their friendship. Smathers was usually present when John Kennedy made his many powerful moves on the opposite and the allegedly weaker sex; and he used John Kennedy like remoras use sharks: hitched himself to the larger predator for a good ride, hoping to avail himself of the leftovers. Smathers occasionally assumed the role of a pilot fish, however, and piloted John Kennedy to his beautiful and sexy prey. Bluntly stated, Smathers acted on occasion as his best pal’s pimp, as did most of John Kennedy’s chums along with several members of his staff—or at least, that is the way the president’s male relationships have been portrayed and written about; and according to Michael O’Brien, Jacqueline Kennedy knew on what her husband’s friendship with Smathers was based. Smathers admitted to O’Brien that Jacqueline was not a fan of his, that Jacqueline did not find him endearing, primarily because John complained to his wife and told her stories about Smathers’ behavior. He was always using me as a cover for himself, Smathers asserted. I was catching hell for his running around, and God knows he was a far worse influence on me than I ever could have been on him.1O’Brien, Michael. John F. Kennedy’s Women: The Story of a Sexual Obsession. Santa Monica: Now and Then Reader, LLC. Kindle Edition, 2011.All things considered, the preceding evaluation of which man imparted the more adulterating influence on which man rings false with an innate sophomoric quality, one most frequently associated with a couple of frat boys using each other as an excuse for engaging in habitually bad behavior; and even though the alleged best friends shared womanizing in common, a few Kennedy historians question Smather’s honesty and loyalty, based on what any reasonable person would consider Smather’s betrayal of his best buddy.

In 1960, George Smathers entered Florida’s state presidential primary and, as a favorite son candidate, opposed John Kennedy in hopes of winning that state’s convention delegates. Why would Smathers oppose his best buddy? According to the Floridian, he found himself sandwiched between John Kennedy and Texas Senator Lyndon Johnson, Smathers’ good southern, non-Yankee pal. Lyndon Johnson was also the Senate Majority Leader.

After learning of his best buddy’s decision to run in the Florida primary, John Kennedy implored Smathers, even demanded that he withdraw from the contest: You’ve got to do this for me, John Kennedy demanded, according to Smathers, who refused: Well, I can’t do it. I’m not going to do it. Kennedy then asked: Damn it to hell, what kind of friend are you? Smathers informed John Kennedy that he did not want Florida ruined and divided between two candidates, the Yankee Kennedy and the Rebel Johnson, a downright odd assertion since Lyndon Johnson was not even on the primary ballot. Another angry exchange transpired. Apparently the best buddies argued back and forth over the issue until the Bostonian finally declared: You really are a no damn good friend, to which he later added: I want to tell you something, you’re not as good a friend as I thought you were. Smathers told his now ambivalent best buddy: What I will do is, after the first ballot, I will instruct my delegates they can go for whomever they want to vote for, either you or Lyndon. John Kennedy still implored Smathers to withdraw from the primary; but the Florida senator remained steadfast and refused. Essentially, Smathers ran against his best buddy to prevent the presumptive nominee from getting the nomination on the first ballot during the 1960 Democratic Convention, a optical tactic endorsed by Lyndon B. Johnson. Smather’s political ploy failed, however: Kennedy was nominated on the first ballot despite Smather’s interference and a late challenge by Johnson.2All quotations taken from Smathers’ interview no. 4 with Donald Ritchie. This interview occurred on September the 5th in 1989. Quotations can be found on pages 78 thru 80.

<https://www.cop.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/OralHistory_SmathersGeorge.pdf>

All things considered, a fellow must ask: what was the point? A fellow could only conclude, in the final analysis, that Smathers betrayed John Kennedy for mere political optics which favored and also made Lyndon Johnson happy. Not surprising, actually, since by all accounts, Smathers was much closer to Lyndon Johnson politically than he was to John Kennedy; but then Smathers did not consider his best buddy to be an outstanding senator with views that he, Smathers, could support. In an opinion related thereto, Smathers also considered John Kennedy to be a poor husband and father due to his womanizing; but then, evidently, Smathers conveniently gave himself a pass.3Op. Cit. Ritchie

Smathers was a typical nineteen-fifties southern Democrat who opposed civil rights legislation designed to assist and equalize poor blacks in the segregated South. Being a civil rights activist was, in Smather’s opinion, as bad as being a Communist. Senator Kennedy’s best buddy was one of nineteen southern Democrat senators, segregationists each, who signed the Southern Manifesto condemning the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Smathers denounced that historical ruling as an abuse of judicial power and blatant judicial overreach. He attempted to diminish the effectiveness of the equal rights measures introduced to the legislature by Republican President Dwight Eisenhower; but Smathers reluctantly agreed to support the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Legislatively, Smathers is better known for his effort to help create the Small Business Administration and the Everglades National Park; and as an advocate for moving Federal holidays to Monday, he helped create the modern three day extended party weekend.

During John Kennedy’s tenure as a senator from Massachusetts, he and his senator friend from Florida often disagreed; and once the senator from Massachusetts became the thirty-fifth president of the United States, their disagreements continued, arguably the most significant and contentious of which was how to deal with Cuba and Fidel Castro. Smathers believed that President Kennedy did not understand the economic influence exerted by Cuba on the state of Florida. A fellow could assert that prior to Castro’s revolution and his expulsion of the MOB from Cuba, the economic influence exerted by the small island under the Batista regime was entirely illegal, not that illegality troubled Smathers in the least; but then, Smathers was also a rabid anti-Communist. During his senatorial campaign, for example, Smathers accused his red-haired opponent, Claude Pepper, who Smathers affectionately labeled Red Pepper, of harboring Communist sympathies. Certainly Smather’s anti-Communist beliefs influenced his opinions and views regarding Cuba; but then, Smathers believed that Castro needed to be assassinated. According to Kennedy historian, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Smathers admitted that he pressured the President, who considered Smathers more than slightly pushy on the questions of Cuba and Castro. Years later, Smathers recalled an evening at the White House when he yet again broached the question of Castro. John Kennedy answered with an angry outburst and display, according to Smathers, who recalled that the President cracked his dinner plate by striking it with a fork and then demanded that Smathers stop mentioning Castro and Cuba. Smathers alleged that he never mentioned the sensitive subject again (Schlesinger 493).

In January of 1964, just two months past the assassination of her husband, Jacqueline Kennedy and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. tape recorded a series of conversations during which the former First Lady discussed her life with John Kennedy and his presidency. For thirty-seven years the tape recordings remained in a vault. Then in 2001, Caroline Kennedy released digitally re-mastered copies of those conversations on compact discs along with a book entitled, Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy. During Schlesinger’s sixth conversation with the former First Lady, he mentioned George Smathers.

The Kennedy historian noted that everyone in the West Wing became baffled by the way the Florida Senator survived President Kennedy’s dissatisfaction. Schlesinger noted: John Kennedy was often angered by Smathers, angered by the senator’s votes on both Medicare and foreign aid. This will be the final test, John Kennedy often commented about Smathers according to Schlesinger; but then Smathers would cast a dissenting vote, like he usually did, only to reappear in the White House yet again, an assessment to which the former First Lady responded: And I used to get so mad at that and hurt, then he’d say … well he just had such charity. Even though Jacqueline stated that her husband was often hurt by Smathers’ political opposition, the President was so charitable that he would not end the relationship, severe the remaining weakened ties between the men: President Kennedy didn’t want to stick it to someone who’d once been a friend, according to Jacqueline. Schlesinger then interrupted the former First Lady and added that Kenny O’Donnell, John Kennedy’s Special Assistant and Appointments Secretary from 1961 until the assassination, despised George Smathers, to which Jacqueline responded: Yeah. And I didn’t like Smathers.

Even though the time arrived during his administration when John Kennedy would not and did not associate with Smathers personally, according to Jacqueline, her husband just wouldn’t ever, you know, finally say: “OK, you’re out. Now we’re enemies.” Kindhearted and charitable John simply allowed the remnants of his friendship with Smathers to continue (Kennedy 280-281).4Onassis, Jacqueline Kennedy. Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy. New York: Hyperion. 2011.

A fellow can only conclude, based on Jacqueline’s often rambling conversations with Arthur Schlesinger and her candid observations about her charitable husband, that the Florida senator and the president ceased to be best buddies at some point during John Kennedy’s brief presidency; but apparently the president just never told the senator.

Politics certainly makes strange bedfellows for true; and, of course, best pals can disagree and still remain best pals; but beyond the male enterprise of chasing women and seducing them, and then childishly blaming each other for their commissions of adultery, a fellow is led to question just what kind of friendship the president and Smathers actually shared, considering the evidence of conflict and political disagreement, considering the doubts of persons close to John Kennedy, including his wife, regarding Smathers’ loyalty. Those doubts, it appears, inevitably lead to November the 22nd of 1963.

Kennedy historian and assassination researcher, John Simkin, who wrote the Assassination of John F. Kennedy Encyclopedia, along with many other books, maintains a conspiracist’s debate website, Spartacus Educational, on which in 2006 he offered the following opinion about the Kennedy assassination: It could be argued that George Smathers is one of the most interesting characters linked to the assassination still alive. That changed, of course, when Smathers died in 2007; but even so, Simkin indicated that he believed George Smathers was actually under the influence of Lyndon Johnson, that Smathers was also aware of the plot to assassinate President Kennedy even before 1963 and that Smathers’ role in the assassination has never been completely explored.

Several of the persons who regularly post on Simkin’s website agree. Due to Smather’s association with then Vice-President Lyndon Johnson, the man who many conspiracists believe masterminded the 1963 assassination of John Kennedy, the Florida senator has now appeared as a conspiratorial suspect in that quagmire and debate. Certainly, the assassination of John Kennedy is beyond the scope of this book. That event is not unlike a black hole from which even presidential light cannot escape; but briefly what follows is Smather’s relative position within a conspiracy that includes a cast of millions.

By spring of 1963, powerful forces began to array themselves against Vice-President Lyndon Johnson in the form of a scandal involving Johnson’s friend, personal secretary and political adviser, Bobby Baker, the man who became the Majority Leader’s secretary in a Democrat controlled senate after beginning as a neophyte page boy in 1943. Baker also became a self-made multi-millionaire wheeler dealer who sold his influence in Washington for large sums of cold hard cash and also ran the Quorum Club located in the Carroll Arms Hotel in Washington, DC. Baker used the Quorum as a sexual outpost where he traded for senators’ influence or bought a senator’s vote with sex provided by a beautiful woman, even two or three beautiful women if necessary. The Quorum Club entrapped many senators in its vice-like grip of debauchery and corruption and one of those senators, assassination conspiracists allege, was George Smathers; and, too, both the senator from Florida and the former page boy from South Carolina had associations through other tendrils of corruption: a vending machine company with questionable government contracts, shady loans from shady banks, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Sam Giancana and the MOB. In the summer of 1963, the constricting tendrils were beginning to close around Baker and his many Washington associates, including Senator George Smathers and then Vice-President Lyndon Johnson.

An investigation into the many dubious financial and the immoral practices of Baker was just about to begin; and that investigation, according to assassination conspiracists, triggered the murder in Dallas, which made Lyndon Johnson president and effectively ended the investigation into Johnson’s connections to Baker, which also saved Smathers. According to the Politico Magazine, Congress began a small investigation into the financial shenanigans and the vivid social life of Bobby Baker, an investigation which grew ever larger and could have implicated the Kennedy administration in a sexual scandal. That scandal would have destroyed Baker and Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Baker’s political patron. In an attempt to forestall the investigation and the resultant potential destruction, Baker drank four martinis at lunch and impulsively resigned his post. The man who was like a son to Lyndon Johnson and was privy to the vice president’s deepest secrets […] ended up serving 18 months in prison on federal tax evasion charges; but the 1963 November tragedy of Kennedy’s assassination short-circuited the Baker investigation, and spared Johnson career-ending ignominy.5“Sex in the Senate: Bobby Baker’s salacious secret history of Capitol Hill.” Todd S. Purdum. November 19, 2013.

<https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2013/11/sex-in-the-senate-bobby-baker-099530> Considering the types of corruption and influence peddling in which Bobby Baker was involved, serving eighteen months in prison was virtually walking scot free; and, of course, President Johnson walked completely scot free.

Following the Kennedy assassination, many of the books and histories written about John Kennedy have questioned Smather’s friendship. In John Simkin’s opinion, Smathers went out of his way to connect the president with the death of Marilyn Monroe, Smathers one final betrayal and his one final large lie about the deceased president. According to Kathleen Collins, a regular poster on Simkin’s website, Smathers was a lying bastard. I am not prepared to offer such a bold assessment; but Smathers behavior and more than a few of his assertions about John Kennedy have caused me, and others, to doubt Smathers’ intentions and his veracity.

According to Victor Lasky, Smathers seldom supported his best buddy and during the 1960 campaign, not only did Smathers oppose John Kennedy in the Florida primary, but during a special session of Congress, held during the 1960 campaign, Smathers voted against each of John Kennedy’s legislative projects. Lasky asserted that Smathers supported John Kennedy’s legislative initiatives less than fifty percent of the time; and Smathers opposed John Kennedy on Medicare because of the wealthy and powerful influence of the American Medical Association in Florida.6Lasky, Victor. The Man and the Myth. New Rochelle: Arlington House. 1966.

Ted Sorensen, John Kennedy’s speech writer and a man the president called his intellectual blood bank, overheard a comment from a colleague who noted: Smathers might have supported John Kennedy when he married Jacqueline Bouvier―but that was the last time. President Kennedy complained to Sorensen about Smathers and remarked that the Florida senator had provided several poor political recommendations regarding the Dominican Republic. And now, Kennedy remarked, he’s trying to tell me what to do about Cuba.7Sorensen, Theodore C., Kennedy. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. 1965.

Regarding Cuba and Castro, according to Warren Hinkle and William Turner, Smathers recommended that an assassination attempt on Castro should be combined with a staged attack on the Guantanamo Naval Base to provide a pretext for an invasion by the United States Military, an invasion that President Kennedy actually opposed. Additionally, Smathers joined Strom Thurmond to demand a military action during the Cuban Missile episode and quarantine, which would have escalated the crisis and caused a conflict that President Kennedy expressly wanted to avoid.8Hinkle, Warren and William W. Turner. Deadly Secrets: The CIA-MAFIA War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK. New York: Basic Books, 1993.

According to Gus Russo, Smathers was associated with Michael McLaney and his brother William, allegedly two CIA operatives who operated anti-Castro, Cuban exile training camps north of Lake Pontchartrain in southern Louisiana. When the FBI raided the McLaney house in Lacombe, Louisiana, on July the 31st in 1963, the agents uncovered a considerable amount of dynamite putatively provided indirectly by the godfather, Carlos Marcello. Russo asserted that Michael McLaney told investigators how he and Smathers had discussed bombing Cuban oil refineries as a way of starting a conflict through which Castro could be eliminated. Also according to Russo, Smathers had a direct connection to Frank Fiorini, also known as Frank Sturgis, a man often mentioned as a suspect in the Kennedy assassination, possibly even the man who pulled the trigger. Smathers’ connection to Sturgis also raised the possibility that the Florida Senator was connected to David Ferrie, Jack Ruby and Lee Harvey Oswald.9Russo, Gus. Live By the Sword: The Secret War Against Castro and the Death of JFK. Baltimore: Bancroft Press. 1998.

Richard Reeves reported that the President became increasingly unhappy with Smathers’ position and his voting record on civil rights legislation. During the return trip to Washington, DC, from Tampa, Florida, on November the 18th in 1963, President Kennedy allegedly commented to Smathers: Goddamnit, George, you’re just knocking my jock off on civil rights. Can’t you take it a little easy?10Reeves, Richard. President Kennedy: Profile of Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1993.One year later, Smathers voted against the John Kennedy instigated Civil Rights Act of 1964 while later he also opposed the appointment of Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court. Marshall was an African-American jurist who John Kennedy had appointed to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961.

Am I attempting to implicate George Smathers in John Kennedy’s assassination? Of course not. But some persons have debated, and are debating, such an implication. The debaters contend that a John Kennedy second term meant increased civil rights legislation since he would not be able to seek nor need to concern himself with re-election in 1968, prompting the dark southern forces to engage in presidential murder. I personally believe this: what happened in Dallas was a very public and grotesque MOB murder, orchestrated by Carlos Marcello and Santo Trafficante, Jr. According to Lamar Waldron, who wrote The Hidden History of the JFK Assassination, while both mobster leaders were incarcerated in federal prisons, they each confessed to their involvement in the assassination, confessed to its orchestration, confessed to ordering John Kennedy’s murder. It is significant to note, according to Waldron, Marcello and Trafficante had assassination plots arranged for three cities: Chicago, Giancana’s territory, on the 2nd of November; Tampa, Trafficante’s territory, on the 18th of November when John Kennedy visited that city with George Smathers; and finally Dallas, Marcello’s territory, on November the 22nd.

For reasons far too complex and complicated to mention here, Marcello and Trafficante canceled the assassination plots for both Chicago and Tampa; and the fact that George Smathers was with John Kennedy during his visit to Tampa on the 18th of November does not mean the Florida senator was involved in any of the plots. My purpose here is merely to cast a reasonable doubt on the nature of the friendship, the nature of the relationship between George Smathers and John Kennedy and to note that I am not the only person who believes that they were not best buddies or that Smathers was an honest and a forthright man.11Waldron, Lamar. The Hidden History of the JFK Assassination. Berkeley: Counterpoint. Kindle Edition, 2013.

Following John Kennedy’s assassination, George Smathers became a putative unimpeachable source for stories and anecdotes about the president’s life, his relationship with his wife and his presidency. Smathers also became a veritable Mount Vesuvius of information about John Kennedy’s sexual conquests and his many lovers, particularly Marilyn Monroe; but Smathers arrived relatively late in the Marilyn murder cyclorama. Frank Capell, for instance, in his 1964 pamphlet about Marilyn’s putatively strange death, did not evoke the name of George Smathers; and the Florida senator did not appear in Norma Mailer’s 1973 factoidal novel. Smathers did not appear in Robert Slatzer’s 1974 apocryphal account of his relationship with Marilyn; and likewise, Smathers did not appear in the accounts of Ted Jordan or Jeanne Carmen. To the best of my knowledge and belief, Smathers initial appearance as a testifier to the relationships between Marilyn Monroe and the middle Kennedy brothers was in Anthony Summer’s pathography, published in 1985, two decades plus three years after Marilyn’s death; and Smathers offered a considerable amount of testimony. Additionally, Smathers’ testaments appeared in the literary efforts of not only Anthony Summers, but also C. David Heymann, Donald H. Wolfe, Christian Anderson and Randy Taraborrelli. I am positive that Smathers’ name and his statements appeared in other books about Marilyn and the middle Kennedy brothers which I have not read; and I am equally positive that Smathers repeated much of the same flapdoodle and invented new. Certainly, a person who talks more than he or she should, from time to time, might confuse or alter the details of yarns told over and over, particularly when the yarn talker recounted said yarns more than a few years after the fact, and even more particularly if the yarn talker happened to be a serial fabulist.

Anthony Summers asserted that he could only find one person close to John Kennedy who was willing to discuss the topic of Marilyn with him, not one family member and not another friend other than Florida Senator George Smathers, yet another political authority figure employed by Summers. By the time John Kennedy ascended to arguably the most powerful political office on Earth, George Smathers had become, in the estimation of Anthony Summers, John Kennedy’s oldest and most dependable buddy; and Summers elevated Smathers to that position despite Smathers’ adversarial and antithetic political shenanigans. Perhaps the other conspiracist writers who interviewed and repeated the testimony of George Smathers felt the same way about the senator; but what follows is a dirty laundry list, so to speak, of Smathers’ allegations and related anecdotes regarding Marilyn and the middle Kennedy brothers. Subsequently, I offer commentary and observations regarding Smathers’ statements, virtually all of which were inconsistent and contradictory.

1. Bobby was the first Kennedy brother to engage in an affair with Marilyn.

2. John purloined Marilyn from Bobby.

3. Marilyn and Bobby did not engage in an affair.

4. Marilyn did not want to wed Bobby because she was only interested in wedding the president.

5. Marilyn created an embarrassing scene on an airplane while flying to meet Bobby.

6. Marilyn attended the Democratic National Convention in 1960 in Los Angeles where she cavorted with the presidential candidate.

7. Jacqueline Kennedy’s sister, Princess Lee Radziwill, also attended the 1960 convention and acted as Jacqueline’s spy.

8. Marilyn frequently visited and often engaged in sexual activities with John Kennedy at the White House.

9. Marilyn often appeared at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue unexpectedly and unannounced.

10. Marilyn’s name was often mentioned in Kennedy family circles.

11. Marilyn was accepted as an intimate of John Kennedy’s.

12. Marilyn traveled at least once to Hyannisport, Massachusetts, to visit the Kennedy family.

13. Marilyn disguised herself as John Kennedy’s secretary and flew with him on Air Force One.

14. Hubert Humphreys and Marilyn, along with several other guests, sailed on the Potomac River in a motor boat with John Kennedy and Smathers.

15. Marilyn sailed on the Potomac River with John Kennedy in the presidential yacht.

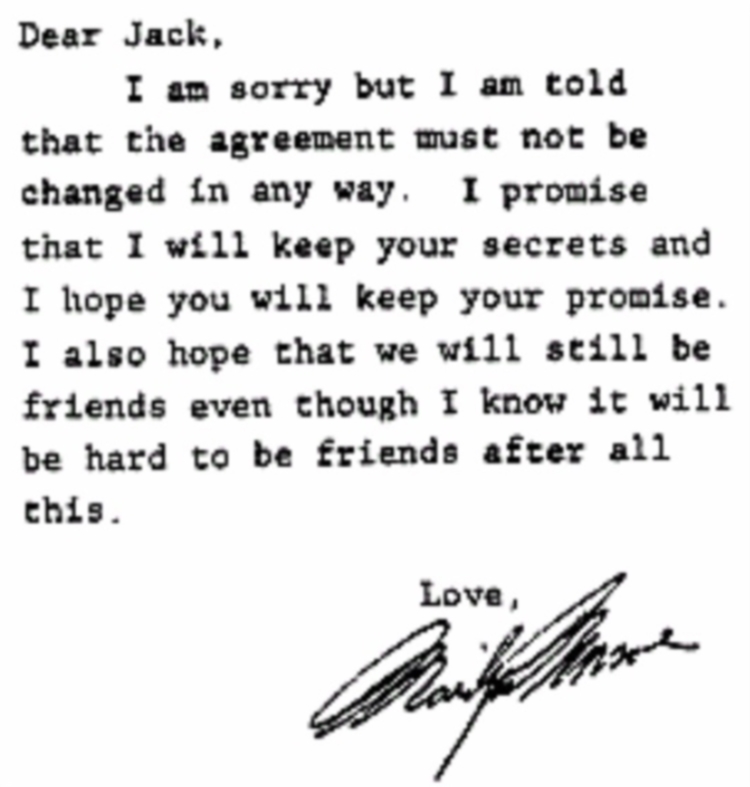

16. John Kennedy asked Smathers to intercede with Marilyn so Smathers contacted:

a. Marilyn and tried to talk to her;

b. One of Marilyn’s friends who he could trust and who talked to her;

c. One of John Kennedy’s friends, who talked to her.

17. John Kennedy ended his affair with Marilyn because:

a. She talked too much;

b. She began to make dicey demands, like asking to visit the White House;

c. The MOB had taped the lovers while they engaged in sex;

d. Jacqueline threatened divorce unless the Marilyn affair ended.

18. John Kennedy was finished with Marilyn after their tryst at Bing Crosby’s estate.

19. The lovers spent the night together after John Kennedy’s birthday gala.

Smathers asserted to Anthony Summers that Marilyn’s assignations with the middle Kennedy brothers began with Robert Kennedy. John Kennedy actually purloined Marilyn from his younger brother. John Kennedy frequently absconded with a female interest of brothers and friends, according to Smathers; but then, boys will be boys, the idiom predicts. Smathers apparently discussed the Marilyn situation with Steven Smith, a Kennedy brother-in-law, a discussion Smathers revealed to Summers: Smith expressed his recollection that Robert Kennedy became entangled with Marilyn first, meaning the first to have an affair with her. Historically speaking, however, the order of Marilyn’s relationships with the middle Kennedy brothers has always been asserted and accepted to be John Kennedy then Robert Kennedy then no Kennedy at all and then they ordered her murder.

As reported by the fantasists Robert Slatzer and Jeanne Carmen, it has been generally asserted and accepted that John Kennedy sent his brother to California to intercede with Marilyn, to pry her loose, as if she had latched onto the president like an Alligator Snapping Turtle, which will only releases its grip after a lightning strike. So Robert, John’s brotherly lightning strike, was sent to convince the famous actress that the President was no longer interested in a relationship with America’s sexual sweet; but, alas, Robert Kennedy succumbed to her charms and become romantically involved with the Queen of Hollywood. Certainly Smathers’ allegation that John purloined Marilyn from Robert contradicted and contradicts what has been, and still is, generally accepted by those who believe Marilyn participated in romances with both of the middle Kennedy brothers.

But then, according to Randy Taraborrelli, Smathers offered the following testimony regarding Bobby and Marilyn: There was no affair with Bobby, though. I can tell you that Ethel had her doubts at first, only because the rumors started right away. But Bobby told Ethel they were not true and she believed him (Taraborrelli 426). Strange. Robert Kennedy was involved in an affair with Marilyn but then he also was not sexually involved with her. Is that actually possible? According to C. David Heymann, Smather’s also testified that John Kennedy directly expressed to him, Smathers, a brotherly concern over his little brother’s illicit shenanigans with the woman Smathers described as a golden goddess with the voluptuous, slam-bang bod (Heymann Legends 264).

I would be remiss if I did not report the following: during his first interview with Donald Ritchie, which occurred on the 1st of August in 1989, Smathers mentioned C. David Heymann and the dubious biographer’s recently published book, A Woman Named Jackie. Heymann quoted Smathers extensively in that publication and asserted that Smathers sat for several interviews with the author. On page 19 of the Ritchie interview, Smathers indicated that he and John Kennedy often discussed The First Lady’s uncontrolled spending. C. David Heymann quoted Smathers’ alleged conversation with John Kennedy about that exact issue; however, Smathers advised Ritchie as follows:

See, I’ve been quoted a lot saying things like that about Jackie. Some of those quotes have been distorted and exaggerated enormously. This latest book that C. David Heymann wrote, I don’t remember ever having seen that guy in my life. What he does is pretty interesting. He says that each one of these quotations, there was an interview that justifies this quotation. What he doesn’t say is, however, I did not make this interview, this was somebody else’s interview that he was gathering up from around in various places.

Certainly an interesting irony, one fabulist questioning the verity of another fabulist while also complaining about being misquoted or being the victim of fabrications. Which fabulist can we believe? At any rate, Smathers did not mention Marilyn Monroe in either of his four lengthy interviews with Ritchie.

The preceding contradictions, and humorous ironies, do not represent Smathers’ only troublesome testimony. Also according to Randy Taraborrelli, Smathers asserted that Marilyn had it in her head that she wanted to be First Lady―JFK’s wife―not Bobby’s. She wasn’t interested in Bobby that way. Anyone who says otherwise doesn’t know what he’s talking about (Taraborrelli 426). The preceding testimony certainly contradicts the accepted marital expectations that Marilyn allegedly expressed to several persons, including the implausible friends, Robert Slatzer and Jeanne Carmen, and other testifiers that the conspiracists have produced over the years. Allegedly Marilyn’s Red Book of Secrets was filled to the brim with expectations and conversations of a Hollywood wedding with the sitting Attorney General of the United States.

For Anthony Summers, Smathers, the old and trusted Kennedy friend, recounted a story he allegedly had been told about a drunken Marilyn who, apparently on her way to visit the attorney general, caused a noisy and embarrassing scene on the airplane; and even though a group of passengers Smathers identified as only they attempted to control and stifle Marilyn’s embarrassing behavior, she could not be dissuaded from repeatedly announcing she was on her way to meet Bobby Kennedy. Conspiracist Donald Wolfe reported that Smathers repeated the same airplane story to Sylvia Chase, a personality involved with ABC television’s on-screen scandal magazine, 20/20. Smathers did not reveal the source of his drunken-Marilyn-on-an-airplane anecdote or a date when that scene might have occurred; and he did not indicate who was on the airplane with Marilyn, who the mysterious they just happened to be. He did not explain, either, how Marilyn could have been intoxicated on an airline flight, acting boisterously while also admitting to an affair with Bobby Kennedy without the press being notified. Considering how virtually everything Marilyn did or said was followed and reported by the press in one way or another, almost religiously, how that titillating and potentially explosive front page scoop escaped their prying ears and eyes remains a mystery indeed.

Smathers reported to Christopher Anderson that Marilyn attended the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. He also reported that Jacqueline’s sister, Lee Radziwill, also attended for the express purpose of spying and reporting on the shenanigans of her brother-in-law and Marilyn, their clandestine dates and assignations, as it were. According to a Lee Radziwill biography written by Diana DuBois, Lee, otherwise known as Princess Radziwill, and her husband, Prince Radziwill, attended the Los Angeles convention at high summer in 1960. At the time, the Princess was six months into a difficult pregnancy which ended with a premature delivery; but even so, she and the Prince were interested in the political fortunes of their brother-in-law. DuBois wrote:

Marginal figures both, they attended the Democratic National Convention as observers, content to follow the Kennedy operation and enjoy the euphoria of Jack’s first ballot victory on July the 13 strictly from the sidelines. From her suite at the Beverly Hilton, Lee talked often about each day’s events by telephone to Jackie, who was pregnant and had remained behind in Hyannisport (DuBois 124).

In the Radziwill biography, DuBois evoked Marilyn’s name only once within the text of a footnote. DuBois asserted nothing about the Princess spying on the Queen.

Often asserted, but nonetheless also false, Marilyn did not attend the 1960 political convention. I presented and discussed that fact in Section 4 within the sub-section dedicated to the fabulist, Clem Heymann. During the week of the 1960 Democrat presidential nominating event, Marilyn was in Manhattan with her husband, Arthur Miller, and her close friend, Ralph Roberts. She did not fly to the west coast until after the 1960 Democratic National Convention concluded. Therefore, if Marilyn was not in Los Angeles and she did not attend the political convention, how could Princess Radziwill have spied on her her brother-in-law cavorting with the Queen of Hollywood and then reported on his cavorting to Jacqueline?

Smathers asserted on more than one occasion, testified unequivocally, that Marilyn frequently visited the White House, that she often flew to Washington and appeared unexpectedly. He also asserted that the lovers engaged in some horizontal grunting on White House sheets. Smathers knew Marilyn visited the White House, he asserted to Christopher Andersen, because he frequently observed the actress roaming the halls therein. Smathers also reported to Anthony Summers that he often heard Marilyn’s name evoked by family members in Kennedy cliques and within the White House, which suggested that Marilyn had been openly accepted by the Kennedy clan, a suggestion Smathers alleged was confirmed by John Kennedy’s friend, Chuck Spalding. Smathers recounted to Donald Wolfe a story by Spalding who recounted that Marilyn once visited the Kennedy compound in Hyannisport, Massachusetts, where she was welcomed as and even treated like a John Kennedy consort. That being the case, why would none of the Kennedys, neither family members nor close friends, discuss Marilyn with Anthony Summers? Certainly an oddity. Still, Smathers offered inconsistent and contradictory testimony regarding Marilyn’s White House appearances, to which I will return later in this section.

Two sources offered testimony to Michael O’Brien which directly contradicted Smathers’ statements. The White House kennel keeper, Traphes Bryant,12Bryant also wrote a memoir, Dog Days at the White House: The Outrageous Memoirs of the Presidential Kennel Keeper, dedicated to the presidents he served and their pets.who apparently knew everything that happened in that complex of buildings, asserted to O’Brien that he, Bryant, never observed Marilyn in the White House and never heard any rumors of a visit by the blonde movie star. Secret Service Agent, Larry Newman, who was very familiar with John Kennedy’s sexual proclivities and the many Kennedy women who visited him in the presidential quarters, corroborated Bryant’s statement and testified that he never encountered Marilyn Monroe. Regarding Marilyn’s possible presence in the White House, Agent Newman testified that he never heard even a rumor that Marilyn had been in the White House.

While all the other men and women who visited John Kennedy in the White House, some of them celebrities, Marlene Dietrich, Richard Adler, Carol Burnett, Danny Kay, Judy Garland, Anita Ekberg and Joan Crawford, just to mention a few, were dutifully logged in by the Secret Service, a White House visitor’s log bearing Marilyn’s name has never been produced; but then, Marilyn, I assume, was given special dispensation by the presidential police just to keep her tryst with John Kennedy a secret, something that their brief relationship, in fact, never was, not unlike the president’s regular trysts with many women, also never a secret.

Do you believe that Marilyn Monroe could have disguised herself enough to appear on Air Force One as John Kennedy’s secretary and remain unrecognized? I do not believe so; that is, unless she disguised herself as a secretarial charwoman. Only donning a dark wig and glasses, as alleged, would not have generated an adequate legerdemain. But then, if Marilyn had been accepted by the Kennedy family and welcomed as an intimate and even visited Hyannisport, why would she need to disguise herself? Smathers was the only source for Marilyn’s alleged jet ride with John Kennedy as she posed in secretarial costume. What exactly is a secretarial costume? No verifiable proof confirming that alleged flight has ever been offered or has ever surfaced. Donald Spoto categorically disputed George Smathers’ claim and asserted that Marilyn never boarded Air Force One.

Smathers reported to Taraborrelli that Marilyn came into Washington unexpectedly on one occasion and that he, along with John Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey and a few other presidential guests, took Marilyn sailing on a motorboat down the Potomac River. Having Marilyn Monroe and Hubert together was a humorous sight, testified Smathers. Neither of them said much to the other during the river excursion. Apparently the motor boat ride—I mean sail—occurred under the romantically pale moonlight. Additionally, Smathers was the only source for the motor boat event; and he never revealed the names of the other presidential guests who joined in that sailing motor boat fun nor the date on which the motorboat sail transpired. As far as I know, Senator Humphrey never even mentioned the event. And once again we do not know if the Secret Service tagged along to protect President John Kennedy?

For Donald Wolfe, Smathers recalled observing Marilyn and the president on the Potomac River in the presidential yacht, no date provided, as usual, and no indication if other guests were also present or if the Secret Service tagged along. Smathers did not indicate from where he observed the presidential yacht outing, from a bridge spanning the Potomac or from another yacht, perhaps. Maybe a black ops helicopter? Once again, though, Smathers was the only source for the presidential yacht excursion, which like the encounter in the motor boat, also occurred under a romantic moon and the silver illumination cast by that lesser light.

At this point allow me to admit that I am slightly confused by the two boating events alleged by Smathers. The terms presidential yacht and motorboat conjure various images and the term sailing sounds oxymoronic when used in conjunction with the term motorboat. In short, how does a fellow sail in a motor powered boat?

Presidential yachts have never been on the endangered species list and more than a few presidents have used Naval vessels as their yachts. In fact, John Kennedy had three yachts at his disposal; but the presidential yacht invariably associated with him was, and is, Honey Fitz, a powered and elegant ninety-two foot vessel, complete with a Captain, an operational crew and a few deck hands. Now owned privately and available for hire, Honey Fitz served five presidents: Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon.

Prior to John Kennedy’s assumption of the presidency and the presidential navy, the yacht was Lenore II, named so by Harry Truman. Dwight Eisenhower then renamed the vessel for one of his granddaughters, Barbara Anne. John Kennedy renamed it Honey Fitz in memory of his maternal grandfather. Lyndon Johnson retained the name Honey Fitz out of respect for John Kennedy; but Richard Nixon renamed the yacht Patricia in honor of his wife. The Nixon Administration sold the aging yacht to a private investor in 1970.

John Kennedy also owned a small twenty-five foot sloop, Victura, a gift from his father when John’s age reached fifteen; and for the remainder of his brief life, he sailed Victura as frequently as his schedule allowed. At his disposal, John Kennedy also had a sixty-two foot sailing yacht, Manitou, which he christened “The Floating White House”; and he also owned a seventeen foot Mahogany speedboat, Restofus, an esoteric reference to an earlier speedboat owned by the Kennedys, Tenofus, which referred to the number of family members. For special on-the-water-meetings with his cabinet or meetings with VIPs, and also to ferry special guests to parties and state dinners, John Kennedy usually employed a fifty-two foot powered and richly appointed Mahogany yacht named USS Marlin, essentially a US Coast Guard Cutter. So, to which of the yachts and boats was Smathers referring?

Jacqueline Kennedy knew about the alleged motorboat excursion, according to Smathers according to Taraborrelli; and she said so during a White House cotillion: Don’t think I’m naïve to what you and Jack are doing with all those pretty girls, like Marilyn, Jacqueline allegedly said to Smathers while they were dancing, sailing on the Potomac under the moonlight. It’s all so sophomoric, George (Taraborrelli 417). Allow me to interject my skepticism regarding the preceding statement attributed to Jacqueline Kennedy by George Smathers. Why would she confide in a man for whom she had no predilection? She admittedly disliked Smathers. Why would she ask him, as if what Smathers thought of her was significant, not to think of her as naïve or gullible? Why would she care? And why did she refer to a motorboat ride as sailing on the Potomac? Undoubtedly, considering the number of times that she and her husband sailed in various sailboats, she certainly knew the difference.

According to the Florida Senator, he accepted a request from the president to intervene with Marilyn in hopes that she would listen and would keep quiet about her affair with the Commander in Chief; but apparently he failed. Consider the following statement offered by Smathers to Taraborrelli regarding his efforts to squelch Marilyn’s talking:

So I called someone I knew, a friend of Marilyn’s I could trust, and I said, “Look, I need you to put a bridle on Marilyn’s mouth and stop her from talking so much about what’s going on with Jack. It’s starting to get around too much.” That’s all I did to end things, my little contribution (Taraborrelli 418).

Which friend did Smathers and Marilyn share, the friend that he could trust? Trust in what capacity? Those would have been a stellar and useful pieces of information; but then, as far as I know and have been able to determine, Smathers never revealed that name; and if he did, then Randy Taraborrelli kept it a closely guarded secret.

However, in Christopher Andersen’s 2013 publication, These Few Precious Days, an examination of the First Couple’s last year together, the author reported the following Smather’s testimony: Marilyn was surprised that Jack was upset. She was in a haze much of the time and, frankly, I don’t think she knew she was spilling the beans (Anderson 188-189). Is it not reasonable and logical to conclude, based on Smathers’ preceding testimony, that he spoke directly to or possibly even met with Marilyn; and even though he did not mention a meeting date or divulge any real details about a possible meeting, his testimony clearly suggested that he made a concerted effort to personally apprise Marilyn of the political situation: she was just a sad and lost cause, unaware that she was talking out of school. At any rate, as far as I have been able to determine, Marilyn Monroe never met nor even knew Florida Senator George Smathers.13After a moderate amount of research, I can confidently assert that Joe DiMaggio, who spent an ample amount of time in Florida, never knew Senator George Smathers.

Eventually John Kennedy began to feel the pressure of his affair with the most famous movie star in the world; but then, all good things must end someday, so the idiom predicts. Marilyn’s indiscreet boasting about her affair with the president caused him a considerable amount of concern: he feared that Marilyn’s loose lips would sink his presidential yacht. In that regard, Smathers offered testimony which appears to contradict his statements that Marilyn frequently visited 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and the president’s quarters.

In 1997, ABC Television broadcast a made for TV production, partly a movie and partly a documentary entitled Dangerous World: The Kennedy Years, a program that I have already referenced herein. George Smathers appeared as a testifier and a witness to the affair between Marilyn and John Kennedy. On camera, Smathers offered the following account:

What happened was that she began to ask for opportunities to come to Washington, to come to the White House, that sort of thing. So that’s when Jack asked me to see what I could do to help him in that respect by talking to her. I then got a fella named Bill Thompson, whom Jack Kennedy liked very much. So he got Bill to go talk to Marilyn Monroe about puttin’ a bridle on herself and on her mouth and that sort of thing and not talking too much because it was beginning to be a story around the country.

Was the affair in which Marilyn and John Kennedy engaged a closely guarded secret or was the affair a national story? It must have been one or the other because it could not have been both.

Randy Taraborrelli’s clairvoyant Marilyn biography was published in 2006, nine years after Smathers appeared on camera for ABC News and invoked the name of Bill Thompson; however, Bill Thompson does not appear in Taraborrelli’s book. Thompson does not appear in Andersen’s 2013 publication, either, nor any of the other Marilyn biographies or literary efforts advancing a murder orthodoxy that I currently have in my possession, including the effort by Anthony Summers, who apparently interviewed Smathers. Also, Smathers’ 1997 on camera statement clearly contradicted his assertions to Wolfe, contradicted his assertion to Taraborrelli, that the person contacted was a friend of Marilyn’s, and contradicted his assertion to Andersen, implying that he contacted Marilyn directly. Three disparate and contradictory stories regarding Marilyn’s alleged inability to keep quiet about her romance with John Kennedy, which in and of itself was, and is, a preposterous allegation.

In my opinion, the testimony Smathers offered to ABC News and also to Donald Wolfe contained a curiosity. To ABC News Smathers testified that Marilyn began to ask for opportunities to come to Washington, which prompted John Kennedy to enlist Smathers’ help with the actress, to dissuade her of such ideations (emphasis mine). To Wolfe, Smathers also asserted that all women, quite naturally, desired to be near the president: Marilyn was no different in that regard. As a result, she began to ask for an opportunity to come to Washington and come to the White House, and that sort of thing […] (Wolfe KE:P5:48/emphasis mine). In short, Marilyn began to make demands. The preceding statement clearly suggests that Marilyn’s demand, or demands, to visit the White House posed a serious predicament for the president, a situation he certainly needed and wanted to avoid: a possible confrontation with his wife. However, and all Smather’s testimony considered, if Marilyn visited the White House, slept there regularly and aimlessly wandered its halls, usually when Jacqueline was either out of town or out of the country, and if Marilyn often just appeared in Washington and at the White House door, both unexpectedly and unannounced, why would she need to request or search for opportunities to visit the presidential mansion? And how did Marilyn avoid encountering Jacqueline when the actress frequently appeared unexpectedly and unannounced at the White House door?

The implications, therefore, are as clear as water in a mountain brook: Smathers told more than a few untruths about Marilyn’s visits to and wandering appearances at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and President John Kennedy never encouraged, never actually arranged nor approved a visit by Marilyn to the White House. We are led to conclude, therefore, based on Smathers’ testimony to ABC News and Donald Wolfe, that Marilyn neither visited nor slept at the White House, meaning Smathers’ simply created those White House tales.

Bill Thompson, just to close the loop on the man, appeared in Michael O’Brien’s Kennedy biography. Like Smathers and John Kennedy, Bill Thompson, who hailed from Florida and was a lobbyist for the railroad’s interests in that state, was also a notorious womanizer. According to O’Brien, Thompson met John Kennedy through George Smathers in the mid fifties. So Smathers’ implication that Thompson and John Kennedy were good friends outside of their relationships with Smathers was false, at least according to O’Brien. In 1958, John Kennedy stood as Thompson’s best man when the womanizer remarried; and according to Thompson’s daughter, Gail Laird, her father enjoyed an interesting relationship with the President. During her interview with O’Brien, Gail described that relationship as sleazy. So, from a relatively concealed position in the background of John Kennedy’s life, Thompson became yet another alleged presidential pimp, a role, according to Michael O’Brien, confirmed by Kennedy friend, Charles Bartlett. Evidently, then, most of John Kennedy’s male friends acted as his unpaid pimp, making them the most generous men of all time; and a fellow might reasonably conclude that most of John Kennedy’s relationships with other men were based on the provision of that unique and very generous service.

In a lengthy statement to Randy Taraborrelli, Smathers recounted his conversations with John Kennedy about the affair with Marilyn and its impact on the First Lady. Her husband’s affair with the Blonde Bombshell, according to Smathers, poured salt in the wounds inflicted by all of John Kennedy’s other innumerable and blatant peccadilloes. Smathers testified to Taraborrelli: Jackie was accustomed to Kennedy’s indiscretions, but this one bothered her. She knew from what she’d heard and read that Marilyn was a troubled woman (Taraborrelli 417). In fact, Smathers asserted, Jacqueline threatened to divorce her husband unless he dumped his troubled blonde paramour. Jacqueline’s divorce threat added to the considerable amount of pressure John Kennedy already felt due to his affair with Marilyn, her overt boasting and her demands to visit the White House; and then, too, John Kennedy learned that the MOB had procured tape recordings of his grunting along with Marilyn’s squeals of delight while they made love at Peter Lawford’s beach house. John Kennedy ended his affair with Marilyn, according to the Florida Senator, due to Marilyn’s loose lips, due to Jacqueline’s threat to divorce him and due to those MOB obtained tapes. I discuss and evaluate those MOB obtained tapes in a later section devoted thereto.

Then, regarding the end of John Kennedy’s affair with Marilyn, for all intents and purposes, Smathers reported to Taraborrelli, Marilyn was just another discarded mistress after her weekend with the president at Bing Crosby’s Palm Springs estate. Smathers recalled only one more unexpected arrival by Marilyn in Washington, the unexpected visit which ended with the already cited motorboat sail on the Potomac River. After that motorboat sail, according to Smathers, he and the president got back at 11:30 PM; but Marilyn did not spend that night at the White House; she stayed somewhere else, Smathers asserted then added: There was no hanky-panky between her and JFK that night. I know because I asked him the next day and he would have happily said so (Taraborrelli 417). I cannot help but wonder: where did Marilyn sleep that night? Despite the impromptu nature of her appearance in DC, according to Smathers, had the usually disorganized actress reserved a room for her evening in the nation’s capital? Or, if she had to make arrangements for accommodations following her motorboat sail, did anyone observe her as she signed the hotel register? Certainly, the clerk monitoring the registration desk saw her. Did she travel with luggage? Did she travel with her usual entourage of hairdresser and make-up artist? Better yet, when she visited the White House all those times denoted by George Smathers, did she visit without her beautifiers? Obviously, Smathers never reported on those essential and troublesome details.

At any rate, based on Smathers’ testimony then, the motorboat sail must have occurred between March the 25th and May the 17th in 1962, when Marilyn traveled to Manhattan for John Kennedy’s birthday gala, a time span of sixty days. So, what happened in Marilyn’s life; and what did Marilyn do during those sixty days? According to April VeVea’s A Day In the Life, Marilyn left Los Angeles only once during those sixty days, a trip to New York City, confirmed by both Donald Spoto and Gary Vitacco-Robles, to consult with the Strasbergs. What follows is an accounting of how Marilyn spent her time beginning in March.

Marilyn moved into 12305 Fifth Helena Drive on March the 8th and 9th, assisted by Joe DiMaggio. Thereafter, she occupied herself decorating and remodeling her recently purchased and modest hacienda until she met John Kennedy at Bing Crosby’s sprawling estate during that late March weekend. On March the 25th, she returned to Los Angeles. According to Gary Vitacco-Robles, she and her poet friend, Norman Rosten, shopped in Beverly Hills before Norman returned to New York City.

Screen tests for Something’s Got to Give began in early April of 1962. While Marilyn prepared to face the cameras at Fox Studios on April the 10th, Evelyn Moriarty, Marilyn’s stand-in, introduced her to Barbara Eden. Then, on Friday the 13th, Marilyn flew to Manhattan to consult with Lee and Paula Strasberg regarding the script for Something’s Got to Give. Even though Lee was suffering from a severe upper respiratory infection, both he and Paula reviewed each scene with Marilyn. On April the 15th, from Manhattan, Marilyn telephoned producer Henry Weinstein and informed him that Lee Strasberg had approved the script; but the script had already been revised. Fox delivered two revised scripts to Marilyn’s apartment between April the 16th and the 18th, resulting in additional scene reviews, before she returned to Los Angeles on the 19th, suffering from an infection she had contracted from Strasberg. Principal photography on what would be her incomplete and final appearance before the camera began on April the 23rd; but Marilyn could not perform due to illness. Through the remainder of April and the first half of May, Marilyn either struggled with filming Something’s Got to Give and the film’s director, George Cukor, or she remained at home, in bed, due to a cold, severe sinusitis or various other viral infections, including laryngitis. She left the set of Something’s Got to Give at 11:30 AM on May the 17th with Peter Lawford and Pat Newcomb. They flew to Manhattan. On the 19th, Marilyn sang “Happy Birthday to You” as John Kennedy watched from his seat in Madison Square Garden; and then on the 20th, she returned to Los Angeles.

Could Marilyn have slipped away from Manhattan, sometime between the dates of April the 14th and the 18th? Could she have traveled to Washington for that late night motorboat sail with President Kennedy, George Smathers, Hubert Humphrey and several other guests? To contend that she could not have done so would simply be dishonest, although it is quite possible that she was already suffering from sinusitis or another infection by then. However, there are more than a few other possible impediments to consider, one of which is John Kennedy’s published itinerary.

On April the 14th, for instance, the president was not in Washington. He was in North Carolina with the Shah of Iran visiting camp Lejeune before returning to Glen Ora, Middleburg, Virginia. On the following day, Sunday, he attended Mass in Middleburg and then remained at Glen Ora. Back in Washington on the 16th, his day was jammed with meetings and other functions, two trips to the Supreme Court and a Boston Youth Symphony concert on the White House’s South Lawn. Tuesday the 17th was even busier than the 16th; but even so, he and Jacqueline attended a private dinner that night for the Indian Ambassador and his wife. Wednesday the 18th was equally busy and after meeting with his brother, the attorney general, and after a National Security Council Meeting followed by a press conference, he departed for Palm Beach and the Easter Holiday.

We can conclude, I believe, that only one night, Monday April the 16th, was available for a meeting between the charismatic president and the charismatic actress and a motorboat sail on the Potomac; but considering Smathers’ assertion, that Marilyn just showed-up in Washington and that the motorboat sail was impromptu, Marilyn’s arrival was certainly fortuitous, finding as she did, the President of the United States, not to even mention Senator Humphrey, free and available. It is worth noting at this point, in consideration of actual reality, the average nightly temperature in Washington between April the 14th and 18th in 1962 was 39ºF, not exactly motor boating weather or conducive for a romantic sail in an open sloop, particularly if Marilyn was succumbing to the effects of an infection, despite what the condition of the silver moon might have been in Washington. And I must note here, with an air temperature of 39°F, it is safe to assume that the water temperature was not much higher, possibly even a couple of degrees colder and possibly just a degree or two above freezing. Water that cold would most certainly have been unpleasant as it splashed about and onto the occupants of a speeding motor boat, unless that ride did not feature a speeding boat. Additionally, a boating accident in those conditions would mean that any person tossed into the water would lose manual dexterity within 3 minutes. The most hardy person would not succumb to hypothermia, resulting in exhaustion and then unconsciousness, for approximately 30 minutes. That same hardy individual could live as long as 90 minutes; but the average survival time in that chilly water is 45 minutes.

Therefore, Smathers allegation that Marilyn flew unexpectedly to Washington, sailed on a motorboat with him, Humphrey and John Kennedy and then spent the night somewhere in the surrounding environs, does not appear to mesh with reality; and therefore I assert that Smathers’ anecdote was a complete fabrication. In fact, Marilyn never visited the White House; and in fact, she never just appeared there unexpectedly and unannounced, like a waif with her suitcases, night gowns and tooth brushing gear; and to assert that she did so is, and was, absolutely ridiculous on its face.

Smathers insisted that Marilyn and John Kennedy spent the night together after the fund raising birthday gala at Madison Square Garden May the 19th in 1962, an insistence which contradicted his statement that the president was through with Marilyn after their meeting at Bing Crosby’s Palm Springs estate. The Palm Springs weekend, the only confirmed sexual interlude shared by Marilyn and John Kennedy, occurred in late March of 1962 and the birthday gala event occurred two months later in mid May; so if the couple spent the night together on May the 19th, then John Kennedy was with Marilyn after Palm Springs in a sexual situation and he was not, therefore, through with her. That goofy misstatement notwithstanding, Marilyn did not spend the night with John Kennedy the night of May 19th following the party at the Arthur Krim’s Manhattan residence.

Marilyn’s date for that evening was Isadore Miller, a fact that virtually every conspiracist fails to mention. After Marilyn accompanied and delivered Isadore to Brooklyn in her chauffeured limousine, she returned to her apartment where she met a fan, James Haspiel, and Ralph Roberts, who gave her a massage until she fell asleep, additional facts never mentioned by the conspiracists. Even Randy Taraborrelli asserted that Marilyn did not slip away for a clandestine meeting with John Kennedy at the Carlyle Hotel, even though that possibility has been asserted by many conspiracists over the years. Taraborrelli stated unequivocally that his years of research indicate that this did not happen (Taraborrelli 438). By contradicting George Smathers’ statements regarding May the 19th, Taraborrelli also effectively contradicted C. David Heymann’s bogus assertions regarding that night. Besides, by the May event in Manhattan, John Kennedy had several new conquests visiting him here there and everywhere, including the White House; and, too, John Kennedy was interested in the quantity of women he could conquer. Marilyn had become an old victory, a notch already carved.

Finally, Marilyn was a woman who kept receipts, all kinds of receipts, fanatically. So I find this odd and certainly revealing: the receipts for the many airline tickets she must have purchased to fly between Los Angeles and Washington or New York City and Washington have never surfaced, so far as I know, despite the worldwide interest in every aspect of Marilyn’s life, despite a search for every morsel of information thereof. In fact, Marilyn only visited Washington, DC, once―with Arthur Miller. At least I am unaware and did not uncover any evidence of another visit to the nation’s capital except that one, when, in 1956, she appeared before the press wearing a white dress, hands gloved, just to conceal her fingernails’ lack of a proper manicure. She advised the paparazzi that she was in Washington to see her husband vindicated before the HUAC; she felt confident that Arthur would prevail.

Smathers only repeated, more often than not, something he had heard or something he was told; Smathers generally offered testimony about Marilyn, John and Robert Kennedy which was secondhand hearsay. Also, considering the major contradictions found in Smathers’ testimony, a fellow is certainly justified wondering, as Smathers remarked about other persons who offered contradictory testimony, if he, in fact, knew what he was actually talking about; but then, perhaps he was, as my saintly mother often remarked about those who constantly gossip about their neighbors and others, perhaps he was talking just to hear himself rattle.

The contradictory testimony attributed to Smathers proves that frequent fabulists, like him, simply cannot keep their fabrications straight. But then, perhaps Kathleen Collins was correct: Smathers was just a liar who simply forget the exact nature and content of all his previously told lies. At any rate, the multitude of contradictory testaments attributed to George Smathers raises reasonable doubt, not only about his verity, but also about the true nature of his friendship with President John Kennedy; and most certainly the only way to view Smathers’ testimonies about Marilyn Monroe and her interactions with the middle Kennedy brothers is with extreme skepticism.