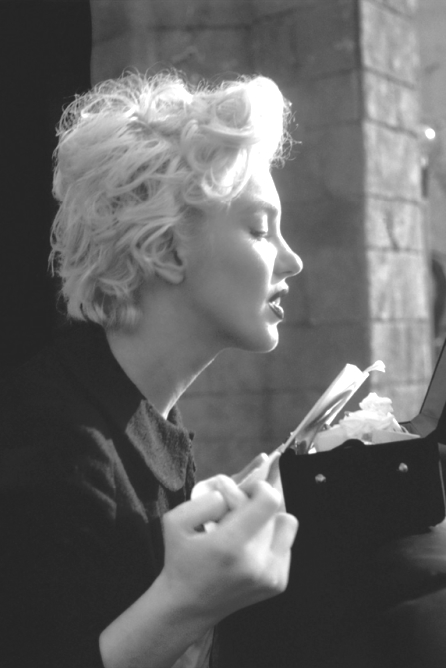

A Decapitated Horse, Frank and Marilyn

While Tuohy did not directly state it, he suggested that Marilyn and Frank Sinatra were sexually involved during Marilyn’s tenure at Columbia, which prompted her to reject Cohn’s advances. Tuohy asserted, once Marilyn’s rebellion filtered through the other Hollywood studios, suggesting that her encounter with Cohn occurred early in her tenure at Columbia, the studio president felt compelled to terminate her, obviously to maintain his dictatorial and heartless image. As I noted previously, Marilyn’s rebellion against Cohn, according to Tuohy, which she allegedly attributed to her love for Frank Sinatra, caused a rift between the singer and the studio president at a time when the latter was preparing to produce the war film, From Here to Eternity. All allegedly occurred while Marilyn was under contract to Columbia in 1948; but, since Marilyn did not meet Frank Sinatra until 1954, according to her legitimate biographers, how could she have been involved with him six years earlier? Well, she could not have been; and that being the case, obviously, she could not have caused a schism between Sinatra and Cohn, especially one that would have impacted Sinatra’s casting in the movie From Here to Eternity: that movie was filmed in late 1952 and released in August of 1953. In fact, Charles Scribner’s sons did not publish the literary basis for that movie, the eponymous novel written by James Jones, until 1951, three years after Marilyn’s tenure with Columbia Pictures ended; and Jones’ massive novel was not adapted into a screen play by Daniel Taradash until 1952.

Eventually, the president of Columbia Pictures gave Frank Sinatra the part of Maggio, allegedly a change of heart immortalized by a decapitated stallion, a famous movie, The Godfather, and a famous movie character, Johnny Fontaine. Many persons have assumed, even asserted, that the young and beautiful starlet mentioned by studio head Jack Woltz, metaphorically Horrible Harry Cohn, during his dinner with the MOB attorney, Tom Hagen, was actually the young and beautiful starlet, Marilyn Monroe; but the legend that Sinatra got the part due to his Mafia connections, as depicted in The Godfather, has always been dismissed and ridiculed by those involved with From Here to Eternity. Director Fred Zinneman, for instance, regularly commented: The legend about a horse’s head having been cut off is pure invention, a poetic license on the part of Mario Puzo who wrote The Godfather. Puzo has also dismissed the urban legend that real events inspired the gruesome scene involving Woltz and the stallion’s decapitated head. According to Alison Cooper, in an article she wrote for the webpage, How Stuff Works, Entertainment Section, Puzo invariably asserted that he did not meet any mobsters until he completed his novel, a worldwide best-seller in 1969 followed by its release as a movie in 1972, fourteen years after Cohn’s death. Additionally, Cooper did not find any evidence during her article research confirming that a real event inspired Puzo to write the scene.1“Was the horse head in

‘The Godfather’ based on a real event?”

Alison Cooper. HowStuffWorks.

2019. Note: Francis Ford Coppola

also contributed to the screenplay.

<https://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/horse-head-in-godfather-real-event.htm>According to Puzo according to Cooper, everything in the book, and therefore we must conclude everything in the movie also, since Puzo wrote the screenplay, developed in his imagination.

Frank Sinatra himself was not exhilarated by the urban legend that he was, in fact, Johnny Fontaine. The implication that he inspired the film’s character angered Old Blue Eyes so much, in fact, according to Cooper, that the singer threatened and verbally assaulted Mario Puzo during a restaurant encounter. Additionally, Old Blue Eyes successfully sued the British Broadcasting Corporation, who asserted that Sinatra’s blue eyes, his olive oil singing voice, along with his MOB connections and associated MOB muscle, garnered him the part of Maggio and inspired the character of Johnny Fontaine.

Kitty Kelley’s casting account in her Sinatra biography is certainly more plausible than the account depicted in The Godfather or declared by John W. Tuohy: Sinatra’s wife at the time, Ava Gardner, persuaded Harry Cohn’s wife to use her influence with the studio president and that landed Sinatra the part.2“Sinatra100: From Here to Eternity:

the second coming of

Frank Sinatra.”

Léan Crowley.

JAZZIZ Publishing. 9 Dec 2015.

<https://www.jazziz.com/sinatra100-from-here-to-eternity-the-second-coming-of-frank-sinatra/>However, in King Cohn: The Life and Times of Harry Cohn, published in 1967, Cohn biographer, Bob Thomas, presented a slightly different account but one that also included Ava Gardner.

Old Blue Eyes was not Cohn’s first choice to portray Angelo Maggio. Both Cohn and director Zinneman agreed that Eli Wallach should be awarded the part: Wallach’s screen test impressed both the studio president and the director. Only the movie’s screenwriter, Daniel Taradash, expressed any concern about Wallach. To Taradash, the Broadway actor seemed almost too muscular, too self-sufficient for the vulnerable Maggio. Certainly the slightly built Sinatra, who had lobbied for the Maggio part after reading the book, was a much better fit physically. According to Thomas, Sinatra enticed Cohn by offering to pay the studio president for the role (Thomas 284-285); but Cohn was intractable. Only a personal plea from Ava Gardner convinced Cohn to test Sinatra. In Africa with his wife while she filmed Mogambo with Clark Gable and Grace Kelly, the beleaguered singer, his career then in a slight decline, flew from Nairobi to Hollywood for a meeting with Cohn and a screen test. Even though Sinatra’s screen test impressed Horrible Harry he still planned to cast Eli Wallach; but, fate apparently intervened: Wallach realized that the film’s shooting schedule conflicted with his commitment to appear in an Elia Kazan directed, Tennessee Williams’ play on Broadway. As a result, Wallach withdrew. Frank Sinatra got the part, according to Thomas, more or less by default; but regardless how it occurred, Sinatra got the part and won the Academy Award in 1954.

Finally, Cohn and Sinatra were not enemies and neither disliked the other. According to Bob Thomas, the two men became good friends during the years when Sinatra was enjoying his initial burst of fame in Hollywood (Thomas 278), meaning the early to mid-nineteen-forties. When Sinatra contracted strep throat during a four-week engagement in New York City in 1949, his doctors ordered complete bed rest. Cohn flew from Los Angeles to NYC and visited the singer each day until he fully recovered. According to Thomas, during Cohn’s visits, the movie mogul read to Sinatra, reminisced about the early days of Hollywood, delivered jokes and even delivered a few songs recalled from his days as a song plugger (Thomas 278). Certainly, any assertion that Harry Cohn disliked Frank Sinatra must be viewed with suspicion.3Horrible Harry Cohn cultivated his heartless and tyrannical image: he believed that image afforded him a negotiating advantage.